Politics Tempts Us to Play God; What Sets the Saints Apart is their Readiness to Let God be God

"Someone has to behave as if God is real."

What sets the saints apart is their unusual readiness to let God be God.

As Stanley Hauerwas says, this is a politics.

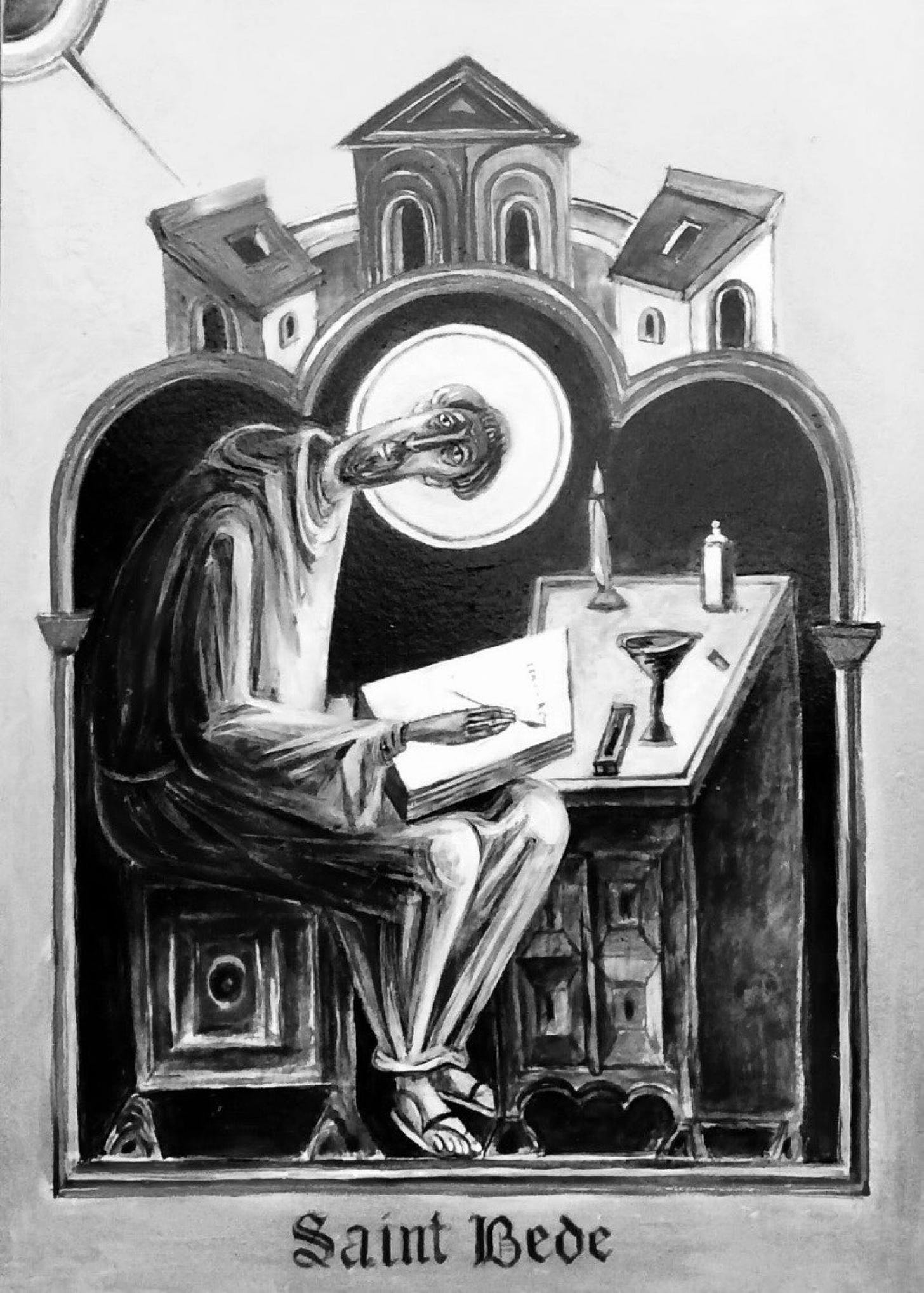

As All Saints and Election Day have approached on the calendar, I have been revisiting some of the “political” writings passed down to us from the cloud of witnesses.

The creed is perhaps the church’s most ubiquitous undercover political document.

Had Jesus not hijacked me away from my well-laid, culturally-approved plans, perhaps I would not be in the position to profess the Apostles’s Creed every Sunday. In so doing, I have often chuckled from my perch up front that the third article requires us to believe in a creature as compromised as Christ’s bride, “the church.”

“I believe in the Holy Spirit,

the holy catholic Church,

the communion of saints,

the forgiveness of sins,

the resurrection of the body,

and life everlasting.”

Lately, however, the creed has struck me not for the belief it beggars but for the items it omits altogether. With the creed, the primal church posited the dogma of the faith; quite simply, the content of its three articles demarcate the convictions which constitute a Christian.

As Robert Jenson says, one who cannot describe these events or trust their veracity is no Christian. Needless to say, there is a great deal to the cruciform life not detailed in the church’s dogma. As a promise about the future where Jesus now lives, the gospel obviously bears implications that are as diverse and myriad as those who hear it in the present.

On what the gospel means for its lived witness, the creed is necessarily silent.

All the faith requires to be reckoned faithful is affirmation of the creed’s brief tripartite summation, “I believe…”

The creed’s use in the sacrament of baptism underscores its function in just this way. This is remarkable! We live— at least, we Christians in America— at a time when many Christians depart from their churches or condemn the churches of others based on alleged articles of faith conspicuously absent from the creed— the atonement, the inspiration of scripture, and sexuality to name but a few. Likewise, Election Day 2024 appears to be the lectionary many preachers and churches have been heeding of late. Many congregations in my area, I've noted, have been offering programs like “40 Days of Prayer for the Election” while others will be hosting candlelit vigils next Monday evening or “Election Day Communion.”

Though all mainline Christians vote in a rough 50/50 Red-Blue split, fellow clergy recently looked at me with both pity and reproach when I offered, offhand, that my congregation was in no way homogenous when it comes to the circles they will fill on their ballots Tuesday.

The clergy’s eyes betrayed an assumed dogma that, once again, does not appear in the creed.

This is not to say that I lack political convictions or that I do not have strong opinions. Nevertheless, the creed rudely ignores both my convictions and my opinions.

However right or wrong history may judge me for my political convictions or my opinions on current events, the creed cares to measure neither.

Instead of my partisan commitments or positions, the creed insists I affirm a claim that appears absurdly ethereal in comparison to the everyday, earthly priorities of politics:

“I believe in the Holy Spirit,

the holy catholic Church,

the communion of saints,

In an All Saints sermon from 2009, Rowan Williams reflects on the saints named by Hebrews 11, writing:

“Without us,” says the writer, “they will not be made perfect.” This is a truly extraordinary claim. We’ve heard about the heroes of the Old Testament, the Judges and the Prophets, those who have suffered atrociously for their faith, those who have performed stunning miracles, “And yet the writer to the Hebrews says baldly without us they will not be made perfect.” Think of that in our own terms. Without us, Francis of Assisi will not be made perfect, without us St John of the Cross will not be made perfect, without us Mother Theresa will not be made perfect…The holiest, the most whole of God's children, reach that wholeness only in communion with us.

Williams begins his All Saints sermon with a passage from Etty Hillesum, a young Jewish writer who died in Auschwitz. On the train to the death camps, she scribbled her final thoughts:

"Someone has to take responsibility for God in this situation. That is, someone has to behave as if God were real. Someone has to make God credible by the way that they meet life and death.”

Someone has to behave as if God were real.

The saints, living and dead, are those who make belief credible by living in a manner that makes sense if the living God revealed in the scriptures is not real. And this is the manner in which the third article of the creed is a thoroughly political confession, for what sets the saints apart, really, is their unusual readiness to let God be God.

Make no mistake, as Stanley Hauerwas says, this is a politics.

Nor is this a politics of passivity or quietism, for many of the lives the church recalls in the creed are those who died as martyrs.

I’m old enough to have noticed that the phrase “the most important election of our lifetime” is a quadrennial invocation. If many believers are to be believed, election season in America is a time when a less than Almighty God apparently needs a great deal from us, not the least to save America or protect democracy. In other words, election season is a time which tempts many Americans to play God, to try to fix ourselves and others, to try to get a handle on what is happening to us and around us.

Politics tempts us to try to play God.

Politics tempts us to do God’s work for him—only better.

And when we think the End is up to us, we can justify all sorts of means.

In Etty Hillesum’s terms, much of the religious rhetoric in our politics is self-refuting, belying a God who is real.

By contrast—

What sets the saints apart is their unusual readiness to let God be God.

As Chris E.W. Green says, the communion of saints reminds us that what is needed in our world is to leave room, to hold space, to wait on the Lord. And that is what the saints do—for us. Exactly so, they not only help us see God more clearly, they also make God look good and make the faith more believable.

With their humble, comparatively simple, often anonymous lives, the saints remind us that time is not one damn thing after the other and that what we call the world is actually creation. The saints stand rudely in the church’s dogma as a reminder that God is not only the author of the story we inhabit but an actor within it; therefore, we can attempt to live in a manner that makes this story intelligible— even at the risk of “losing.” We can, then, let God be God.

Put another way, the creed ventures the claim that Kamala Harris and Donald Trump simply aren’t as interesting as Francis of Assisi or Macrina the Younger.

To quote from Rowan Williams’s sermon again:

“Witnesses establish the truth by giving evidence. It really is as simple as that. When we celebrate the Saints, we celebrate those who have given evidence, who have made God believable by how they have lived and how they have died. The saints are the people who recognise that arguments will finally not win the day. God does not make himself credible by argument. God does not respond to our doubts, our intellectual querying, our uncertainty, by delivering from Heaven a neatly annotated list of logical propositions with which we cannot disagree… God deals with us by our life and a death, by Jesus. And God continues to deal with us by lives and deaths that make him credible, that make Jesus tangible here and now.

That is, God deals with us not by agreeing to the be totem of our political aspirations or the balm against our political fears.

God deals with us by calling forth lives that make it possible to believe he’s got the whole world in his hands.

And those hands bear holes.

Just so—

The communion of saints is not only a political declaration, it is gospel.

It is a promise of pastoral comfort in a world beset by anxieties.

The saints remind us what is possible in a frightening world as a member of the totus Christus. Long after another of the most important elections in our lifetime recedes into history, the communion of saints is the good news that the Father will remember what his Son’s Bride in the Spirit has remembered, the lives of those who, in their ordinary and imperfect ways, made God real.

In a world of cynicism, skepticism, and both-sidesism, Love alone is credible, says Hans Urs Von Balthasar. But the love that is credible alone is the Love made tangible in the lives kept eternally in the creed’s third article:

“I believe in the Holy Spirit,

the holy catholic Church,

the communion of saints.”

Thanks for a helpful, faithful word centered in the community and word that is Christ.

Thank you.