I am the Preacher-in-Residence for the Lily-funded and Mockingbird-supported Iowa Preachers Project which kicked-off today in Des Moines at Grand View University. My title comes with no job description, glory, or pay, but I’m happy to meet preaching fellows and mentors from different traditions, experiences, and places.

This evening Ken Sundet Jones planned a “Preaching Slam” for the cohort, in which the mentors and myself needed to preach with little warning on an unorthodox “text.”

Each of us had as our preaching text a different work of art. Ken’s reasoning behind the exercise is that every preacher should be ready to find a way from whatever situation that encounters them to the gospel.

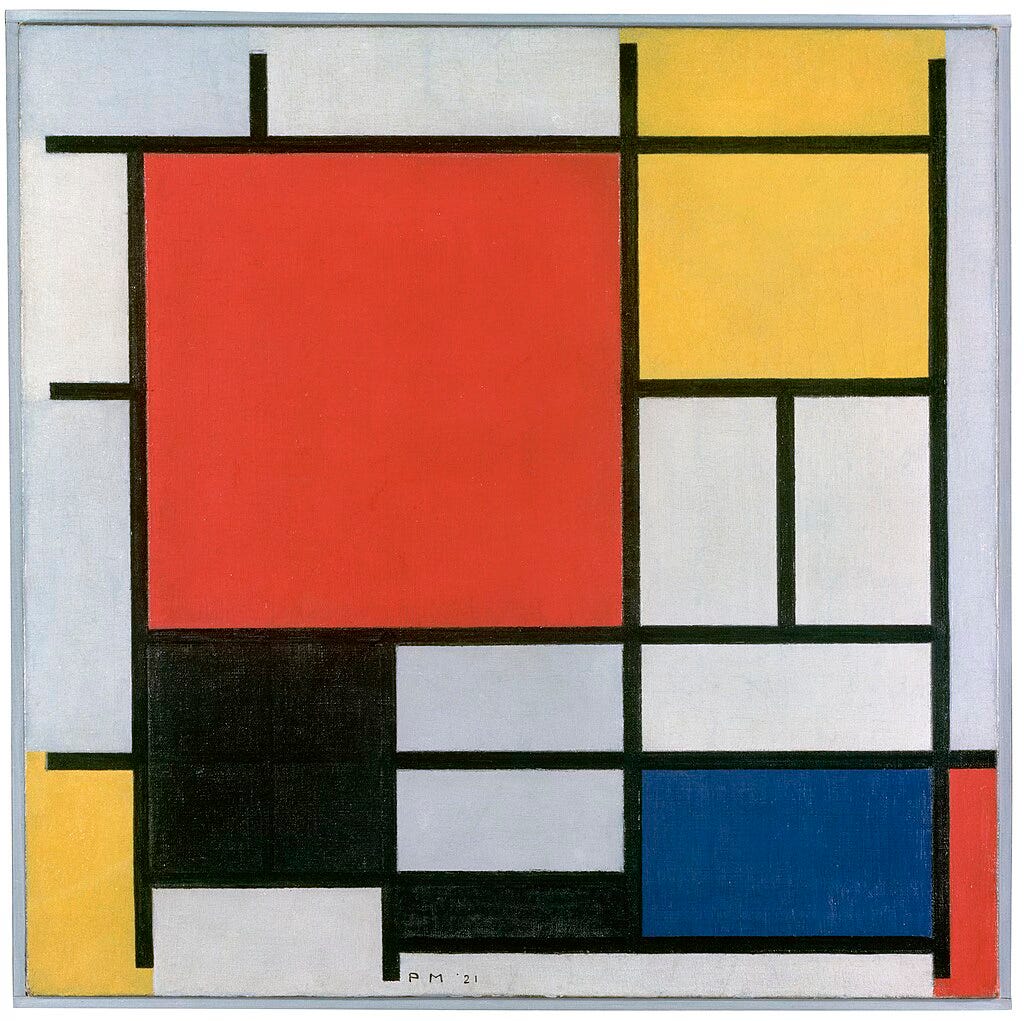

My “passage” was Piet Mondrian’s Composition in Red, Yellow, and Blue.

As the Preacher-in-Residence, I got a bit more heads-up than the other preachers on the docket last night (only a little), all of whom handed over the goods in ways that gifted me faith all over again.

I’m no Sister Wendy, but as an undergraduate student, I enrolled in so many art history courses that I could have graduated with a minor in the department. I took several classes on modern art taught by an elderly professor from Spain who chain-smoked cigarettes outside of class and— we all suspected— drank Port inside of class. She often reminisced about her love affair with Pablo Picasso in a level of detail that begged for Cubist abstraction.

I remember the mechanical gear shift sound as the slide of the painting fell into place. She always held the microphone too close to her lips. The yellow, orange, and amber that appeared on the drop down screen warmed the darkened lecture hall. Her voice whispered awe as she helped us to see Van Gogh’s final and most famous draft of the Sower.

“He’s a preacher,” the proud, avowed atheist explained the figure in the straw hat to us, “He is a little Christ, working under a bright, living halo of a sun, scattering the gospel across the ground he travels, trusting the seeds to take root in the earth.”

I can’t tell you how many seeds I’ve cast that appeared to get tangled in thistles and weeds as soon as they left my lips. So many other sermons fall, stillborn, through my fingers just as I’m drawing my hands from the seed bag. It’s so simple an undertaking, sowing seed, the artist did not need to depict any other laborers in the field.

The painter painted only a single preacher.

Nevertheless!

Only those who sow the word know how it is hard work to sow the word.

Therein lies its peculiar potential for loneliness.

As Karl Barth described the sower’s conundrum:

“As preachers, we cannot speak of the God who is God. It’s literally impossible. But as preachers, we must speak of the God that cannot be spoken.”

It is hard work to sow the word.

Just so, if your fields look fallow to you, if the fruit of your work would lead listeners to conclude that you’re always aiming for rocky terrain, if you’ve spent more time and effort sowing words other than the gospel word, then first things first. Let me hand over the goods. Before I speak about God by way of Composition in Red, Yellow, and Blue, allow me to speak for God.

As Luther said, no one can self-apply the promise so let me do God to you:

In the name of Jesus Christ and by his authority alone, I declare unto you the entire forgiveness of all your sins— especially all your ill-sown seeds.

If you have preached as though its up to us to continue the Kingdom movement begun by the dead Jesus, you are forgiven.

If you have pretended that they teach advice-giving in seminary and doled out life lessons and practical wisdom from your bag of seed, take it from me— I’m speaking for God— you are forgiven.

If you’ve made grace cheap by muddling the gospel with the law, if you’ve made the mistake of not believing your listeners are always experiencing an existential crisis, you are forgiven.

If you’ve preached sermons that did not need God to be a Jew, who lived briefly, died violently, and rose unexpectedly, well that same God— Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim— forgives you.

You are forgiven.

And more so than absolution, hear the good news, which is always a promise about the Future.

Because Jesus lives with death behind him, all the seed you have sown will flower in the fullness of time. Every promise you have proclaimed in light of the resurrection will come true exactly because your gospeling, however imperfect, has been Jesus’s address of himself. Your words, therefore, will not return to the Lord in vain.

Even in your worst sermon, the word— your words— is not fettered.

The Word works what it says.

Through you (talk about faith alone).

Around the same time Karl Barth was writing about the irony which binds preachers (We cannot speak of God. We must speak of God), the Dutch painter and art theoretician Piet Mondrian was pushing modern art into ever greater abstraction. In the name of an unchanging universalism, Mondrian sought to expunge any elements of concrete reality from his art. Mondrian first articulated what he termed “Neoplasticism” in the journal “The Style.” Neoplasticism sought to purge even traditional artistic principles that modern art had kept in place, especially figure-ground opposition. Thus Mondrian reduced his most famous series of work, Composition in Red, Yellow, and Blue, to simple flat geometric elements.

Van Gogh’s kinetic, halo-like sun became a square of yellow.

Piet Mondrian rid his art of figure-ground opposition because such a way of ordering images— ordering— implied a transcendental order beyond reality.

Now, there is no way you could conclude this was the artist’s intent simply by gazing upon Composition in Red, Yellow, and Blue. Neoplasticism produced the sorts of paintings about which my kids opine too loudly at the National Gallery, “I could paint that.” And, as much as I hate to sound like the guy hating on modern art, the truth is: they could paint that.

It’s no accident that with modernism the explanatory card on the museum wall next to the frame became as important as the art itself.

In his book The Painted Word, Tom Wolfe observes that once the church was no longer art’s primary patron, artists no longer had the public in mind in their work. After the medieval church’s patronage, art was cosseted by royal courts for royal consumption. Later, in the years just before World War I, art migrated once again, this time into a small, chic circle of artists and theorists, all of whom lived in a handful of cities around the world and who had one another as their primary audience. It’s not incidental, in other words, that Piet Mondrian self-identified as both an artist and a theoretician.

As Tom Wolfe writes:

“The chic of modernism put a heavy burden on theory. Each new movement, each new ism in modern art was a declaration by the artists that they had a new way of seeing which the rest of the world (i.e., the bourgeois) couldn’t comprehend. This is where theory came in.”

Art theory thus went from an enriching element in conversation to an absolute necessity.

Art now required explanation.

Wolfe continues:

“In no time these theories seemed no longer mere theories but axioms, part of the given, as basic as the Four Humors had once seemed in any consideration consideration of human health. Not to know about these things was not to have the Word…In short, the new order of things in the art world was: first you get the Word, and then you can see.”

In short—

With works like Composition in Red, Yellow, and Blue, modern art privileged explanation over presentation. And the theories which informed those explanations had not the world as its audience but the small, chic cliques— cénacles— which produced them. In order to see a work like Composition in Red, Yellow, and Blue, you first need to receive the Word. But that Word was a word proclaimed only to some.

It is not seed meant to be scattered in the world, sown all over the world.

For the sake of the world.

Terrence Malick’s 2019 film A Hidden Life depicts the witness and martyrdom of Franz Jägerstätter, an Austrian Christian who refused conscription by the Nazis. Towards the end of the film’s first act, Franz walks into his village church where he must have gone to pray or to meet with his priest.

Inside the church, Franz finds a painter, Ohlendorf, retouching the church’s frescoes. Standing on scaffolding, the painter towers over Franz, and asks Franz to hand him up a piece of coal. As he turns to his work, restoring an image of the holy family, Ohlendorf reflects on the ultimate vanity of his project. The artist confesses to Franz a pressure which practitioners of the preached word can also feel. Looking up at God and his mother, Ohlendorf laments that in all of his work, drawing and painting, he’s never once managed to capture the true Christ.

When I was a graduate student, I attended a series of lectures the Lutheran theologian Robert Jenson delivered for undergraduates and faculty members. Though the attendees recognized that Jens was one of the most brilliant theologians America has ever produced, some listeners, though curious, were openly hostile to his gospel.

One skeptical student in the lecture hall was undeterred by Jenson’s arguments and persisted in trying to poke holes in his logic:

“Wasn’t the resurrection supposed to signal the conclusion to God’s history? Doesn’t the New Testament indicate that the world was about to end? Didn’t Paul and the apostles expect Christ to return in their lifetimes? Why has God delayed? Does the church have an answer to those questions?”

I turned my gaze from the argumentative undergrad to the white-haired theologian. Robert Jenson revealed the slightest crease of a smile, and finally he responded nonchalantly to the skeptic’s question with a brilliant six word reply.

“Why has God waited?

His answer:

1) Because

2) He

3) Wants

4) To

5) Include

6) You

I saw the argumentative undergrad furtively raise his hand to rebut the theologian, but Jenson smiled again and quickly said, “And so, you see, the answer to the question of God’s delay is also the answer to your last question. The church not only has an answer to the question of God’s delay the church is God’s answer to the question.”

The next day I said to Jens, “I attended your lecture yesterday.”

“Indeed,” he said.

“Because he wants to include you,” I repeated his reply, “Are you suggesting that, in the End, all will be saved?”

He smiled again.

“Sometimes I catch myself thinking I’m a universalist…” and his voice trailed off and he chuckled to himself:

“My boy— you’re a Christian, which makes you a sower of the word. Rather than speculate about what God will do ultimately one day in the future, why don’t you do something about what we know God, in fact, has done? We know God desires to save all and we know he has allotted precisely this time for sowers like yourself to sow the seed that it is gospel. So, rather than sit in lectures and posit speculative questions that put all the burden on God, why don’t you go and do the work God has given you to do?”

“Someday I might…” the artist Ohlendorf says to Franz, “Someday maybe I’ll paint the true Christ.”

Of course, the irony is that just yesterday morning God spoke to us in this place. And after we received a word from God, the Lord Jesus made himself an object in our hands and on our lips.

That is, the true Christ cannot be painted anymore than charcoal on canvas can fully capture the you you call you.

The gospel needs no more content than the simple sentence, “Jesus is alive.” The true Christ is not dead, and though he speaks ceaselessly and makes himself reliably available he nonetheless refuses to sit still and model for an artist.

Christ is risen.

Indeed he has a body.

A body which includes you and you and you and you and you and you and you and you and you and you as his mouth.

Mondrian was absolutely wrong to purge all particularity from his art in the hope of capturing the universal. The particular— a concrete word, a word that, as Jens writes, can never be preached the same way twice— on the lips of one sinner to another sinner— just is how the cosmic Christ sows his seed in the world.

In spite of the parameters of this exercise, I’m a preacher.

This isn’t a talk.

It’s a sermon.

So I must keep talking until I touch upon a text.

The New Testament Book of Hebrews proclaims that “Faith is the conviction of things not seen.”

Therefore, said Martin Luther, that which is to believed, God and his goodness, must be hidden.

That is, the substance of faith is not reducible to stable images or static illustrations. Instead the substance of faith— the beauty of the Infinite— is hidden under its opposite.

The Lord Jesus has no more obvious opposite than those whom he calls to sow the word.

He has no better hiding place than your lips.

This is precisely why Hebrews 11.1 goes on to say that “Faith is the conviction of things not seen, the assurance of what can only be hoped for.”

In other words, faith is hope, convicted trusting hope.

In what?

In the word of gospel assurance on the lips of a preacher.

A year ago today, I stood in my congregation’s graveyard and watched as an old man, weighing perhaps no more than one hundred pounds soaking wet — he was battling cancer, finished filling the grave of the dearly departed. Wheezing from the effort, he dusted the mud off his pants and then quickly left to go package food at the church’s mission center. Mike was just one of a dozen or so volunteers who gave up the better part of their Thursday to get the dead guy where he needed to go and get the living he left behind where they needed to be. Neither Mike nor the rest of them knew the deceased, a circuit-riding sower who died after a century of living.

Mike’s long battle with cancer is nearing its Appomattox moment.

As the cemetery manager, Mike is on my staff. I checked in with him before I left for the airport this week. I was not surprised to learn that Mike needed to hear what Mike always needs to hear. Mike has a past the details of which I can only speculate, an estranged son and too much time wasted in whatever far country he found himself. The dark cloud that follows him is drawn in such thick and obvious brushstrokes I think of him as a Charles Schultz character. A Pig Pen of regret, his melancholy abides as reliably as Linus’s blanket.

Mike is afraid to die. Even before he was dying, Mike feared what would happen to him after he died. He’s needed a lot of seed scattered his way. And he needs still more.

Before he assumed the cemetery duties after retirement, Mike owned an art gallery in Fairfax, Virginia. Today, all over the house where he’s slowly dying, are paintings, wrapped and stacked on the floor.

Mike is literally surrounded by beautiful images, but he is desperate for a particular word.

Desperate not for explanation, like all those cards affixed next to frames on museum walls. He is desperate for preachers to present Christ to him. He is desperate and dying not explanation but for proclamation.

In 1500, Matthias Grünewald painted Karl Barth’s favorite image, the Isenheim altarpiece depicting John the Baptist’s long bony finger pointing at Christ and him crucified.

A little more than four hundred years later, Piet Mondrian gave us instead simple geometric elements in red and yellow and blue, all lines and flatness and and right angles so as not to imply the ordering of a Creator with a capital C.

Which is to say…

To those of you in whom and under whom Substance of faith, is hiding— his sowers, his preachers:

No one else is going to do your job for you.

Mike does not need you to skewer pop culture. He has Andy Warhol for that.

Mike does not need you for your political hot takes. Banksy can do that far better than you.

And Mike does not need your advice. Not when we all have Nick Cave’s Red Hand Files.

Mike needs a promise.

Mike needs a promise that can only come from the true Christ.

And the true Christ, as effing crazy as it sounds, is you all gathered around word and wine and bread.

Just so, I will end with the good news with which I began.

In the name of Jesus Christ and by his authority alone, I assure you:

Every promise you proclaim in light of the resurrection will come true exactly because your gospeling, however imperfect, is Jesus’s address of himself.

The true Christ cannot be painted.

But the Word will work what you sowers say.

“‘Mike, Jesus lives for you!” I promised him on the phone on Friday.

It was a particular moment irreducible to yellow, red, and blue.

But, I’ve been at this long enough to know the particular was universal.

“Please keep proclaiming it,” he said, “My trust in it only lasts the time it takes to go in one ear and out the other.”

The Beauty of the Infinite