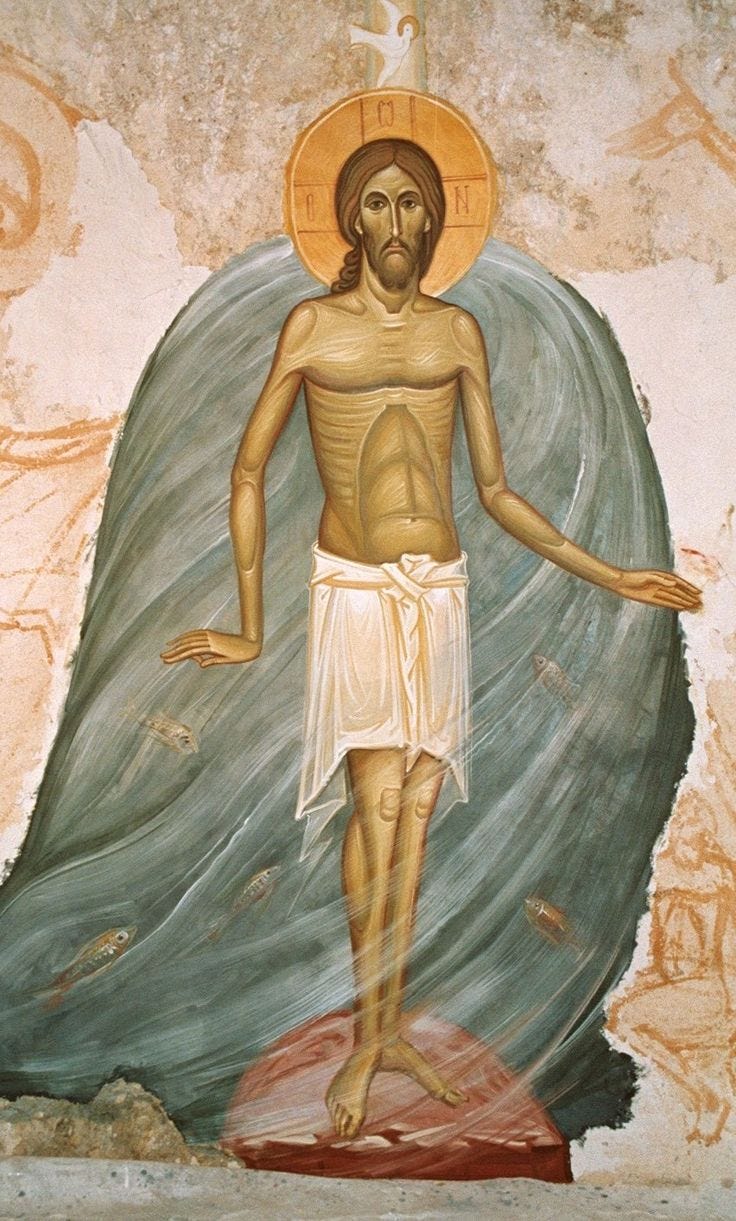

Romans 6.1-11

Despite the dogmatic strictures laid out by various tribes, the New Testament sets forth no single interpretation of baptism. From John the Baptizer to Paul the Apostle, baptism is both pure promise-making or indicative-assuming summons. Depending on the scriptural text, baptism is an event of the Holy Spirit that itself saves unconditionally or a pledge of allegiance to Christ the King. Baptism is an act of individual repentance or it’s an act applicable and effective for that aforementioned individual’s entire household.

Generally, however, the scriptures permit two distinctions:

To those not yet baptized, the sacrament is pure gospel— baptism saves.

To those already baptized, the saving fact of it now interprets existence as a whole.

Both emphases, it’s crucial to note, seek to prevent faith becoming a matter of individual subjectivity. You’re not saved, in other words, because you have decided to follow Jesus. In both instances above, baptism fundamentally names an alteration of the convert’s reality— a change in reality made so by the agency of the Spirit. The Holy Spirit is the fact of baptism whose effect is an alteration of the recipient’s reality.

Baptism is for preaching, the Reformers insisted.

The offensive, gratuitous, and unconditional nature of the gospel is so just to the extent that the church recognizes baptism as an objective event not a subjective one.

That is, baptism saves.

Full stop.

While the New Testament knows no single presentation of baptism, the more extensive treatments of it concern baptism’s past tense. For example, Paul addresses this coming Sunday’s lectionary text to those already baptized. Having handed over the goods of the gospel of grace, Paul anticipates the obvious next question, “If we’re just going to be forgiven anyways, why can we not continue indulging ourselves?” Robert Jenson jokes that the first answer to Paul’s anticipated question ought to be, “Because God will punish those who ask such stupid questions.” Even though such a retort is not without gospel wisdom, the doctrine of justification refuses it as an entire answer. The “It’s a stupid question” response fails to pay attention to baptism’s past-tenseness in Paul’s argument— which, in fact, is its argumentative force.

“If we’re just going to be forgiven anyways, why can we not continue indulging ourselves?”

In writing to the church at Rome, Paul seeks to remove sin and good works both from the sphere of subjective human choice.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tamed Cynic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.