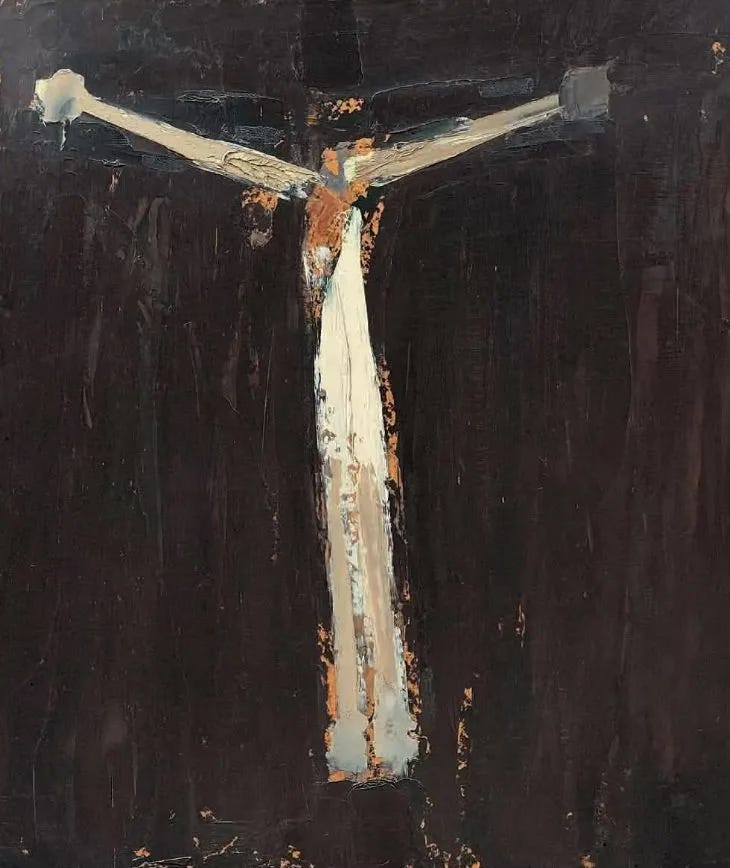

Amazing Dis-Grace

on Fleming Rutledge's The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ

I remember a sermon I heard preached in Miller Chapel when I was a student at Princeton Theological Seminary. In an artful, show-don’t-tell way, the preacher for the day drew an unnerving parallel between Jesus’ death upon the cross and Matthew Shepard’s death, beaten and tied to a barbed wire fence in the Wyoming winter. Shepard, one observer noted, was abandoned and left dangling on the fence “like an animal.”

The season for that sermon was Lent I believe. I can’t recall the specific text nor can I recall the thrust of the preacher’s argument, but I do remember, vividly so, the consequent chatter the preacher’s juxtaposition provoked. On the one hand, my more conservative classmates bristled at an ‘unreligious’ story being equated with the passion story. The parallel with Matthew Shepard, they felt, mitigated Christ’s singularity and the peculiar pain entailed by crucifixion. “Christ was without sin and Matthew Shepard was…a sinner” I remember someone at a lunch table being brave enough to say aloud what others, no doubt, were thinking.

On the other hand, my liberal colleagues, who typically had less use for the cross, applauded the sermon, seeing the mere mention of a gay person from the pulpit as an important social justice witness. They saw both Matthew Shepard and Jesus Christ as victims of oppression against which we’re called to minister. Where conservatives saw Christ’s cross as unique, they saw it as symbolic of the unjust sacrifices humanity repeats endlessly.

Both groups of hearers received the day’s message according to the reified political and theological lines we had brought to chapel that morning and, in doing so, we unwittingly underscored Paul’s insistence in his Corinthian correspondence that the message of the cross is deeply offensive to the religious and ill-fitting to the assumptions of the secular. The religious will forever conspire to mute the cross’ offense, and the secular will always prefer more palatable notions of justice, not to mention more charitable appraisals of humanity.

Only now, having reread Fleming Rutledge’s book, The Crucifixion, am I able to grasp the word the preacher was likely attempting to proclaim that day in Miller Chapel.

The preacher was not announcing that Christ died a martyr’s death, a victim of injustice in solidarity with other persecuted victims. Nor was the preacher suggesting Christ’s death was of a type endlessly repeated rather than absolutely singular.

The preacher was focusing not on the fact of Christ’s death but on the manner of it. The manner of Christ’s death, the impunity of it, is what proved to be a stumbling block to us students every bit as much as the Corinthians.

Like Matthew Shepard, Christ’s death was primarily one of shame and degradation.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tamed Cynic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.