Hi Friends,

To kick off the Advent season, I thought you might enjoy this conversation I shared a few years ago with the inestimable Fleming Rutledge. Thanks to the (evil?) powers of A.I., I’ve included a transcript of the conversation below.

As always, thank you all for the questions, comments, and encouragement you send my way. I’m grateful for the community you’ve helped create through this space.

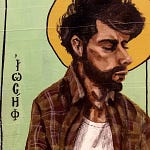

— J

Welcome to Crackers and Grape Juice, where we talk about faith without using stained glass language. On behalf of my partners, Joanna Hartelius, Teer Hardy, and Taylor Mertins, I am the commander of this podcast ship, and my name is Jason Micheli. Our guest today for this latest episode is the one and only...

Fleming Rutledge. Fleming is a hero of mine. I think she's the best damn preacher in the world, and I also count her as my backup wife should anything happen to my beloved. Fleming has a new book out called Advent: The Once and Future Coming of Jesus Christ. And so she joined me for a conversation about this book and the season of the second coming called Advent. And we've also gone beyond just this conversation with her. We have set up a Christmas that in Fleming's honor we are calling Advent Begins in the Dark. You can find these devotionals by going to AdventBeginsInTheDark.com. You can subscribe there to get the daily devotionals by email. You can also go to our Crackers and Grapefruit Facebook page and there join a private group for Advent Begins in the Dark where you can discuss the devotionals with a group of 300 of your closest strangers and go a little bit deeper.

Devotionals are being written by us from the podcast as well as other people from our constellation of listeners and friends. So you'll be getting devotionals from people like Will Willem and Fleming herself and a host of others. So without further ado, I want to just let you know also, also news on the podcast front, we have added an official producer to this show. That's right. We're moving up in the world. Tommie is now serving on the team in that capacity. So give her a shout out for the good work that she is doing for us. And you can do that by finding our podcast on iTunes and giving us a rating. You can go to our Facebook page or our website and share it on all those different social media channels. Share the love, express your gratitude. We didn't ask for a damn penny from any of you on Giving Tuesday instead of being manipulated with hashtags, we're just asking you to pass it along and pay it forward. So that's it.

Enjoy this conversation I had with Fleming.

Have you got more of a beard now? No, it's the same. It just looks different. All right. All right, Jason, what do you want to talk about today? Advent. Oh, all right. I assume you're ready to do that. Yes, I am. So I have your Advent book here.

And so I thought maybe we could start by you connecting your two most recent books. And so it seems to me that your emphasis on rectification in your book on the crucifixion connects to God's commitment to return in Advent. So just talk about Advent in the context of rectification. It's really extraordinary that you should start with that because I do have this quotation here that I want to read and I was thinking that it didn't really necessarily fit into the book.

program for today. But if you are talking about rectification, then it certainly, most certainly does. I've got two books that I'm reading that I want to talk about. I usually have three or four books going at once, as I think most readers do. And I'd like to read something from Charles Dickens' great novel, David Copperfield, which I had never read before, incredibly.

And it brings up the whole matter of rectification very strongly, not that Dickens had that in mind, but that's what it hit me. This is a 900 page novel, so I'm only halfway through it. And I'm laboring against Dickens' well-known sentimentality, which bothers me, but the greatness of Dickens does continue to override that problem. And I'll give an example, which is related to rectification.

This is a scene from the book, it's a very moving scene, in which little Emily has run off with a scandalous young man. And the situation is really very distressing because she is so much beloved by her uncle who adopted her when she was little. And he vows that he will go and find her and bring her home. Sounds like John Wayne looking out, running after his niece through thick and thin, but with a very different frame of mind say the least. He's ready, John Wayne, as you will remember, was ready to murder his niece, rather than bring her back into civilized society. And so we have to hear a couple of different images of ways to face and come to terms with sin, suffering, distress, human failure, and the enormous waves of recrimination that reverberate through a human community when there is an episode of sin and or evil. So the situation is that the uncle, Mr. Peggati, has vowed to go and find his niece, who is certainly in a distressing set of circumstances because the young man that she's been seduced by has no intention of marrying her. And her uncle is a very moving scene and I won't read all of it at all. I'll just read this short part. At the very end of the chapter, young David Copperfield says that he cannot forget the solitary figure of the uncle Toileon, poor pilgrim, and recalling his final words. I'm going to seek her far and wide. If any hurt should come to me, remember that the last words I left for her was.

My unchanged love is with my darling child and I forgive her. Now that's one of the choke up moments that Charles Dickens gives us on a regular basis, but it is a Christ figure. The uncle is clearly a Christ figure and Dickens certainly was some kind of a Christian because he often has moments in his books where you can see it coming through the the uncle who is going to seek for the lost sheep, even if it comes to his own death because he's going into dangerous places where there are all sorts of unsavory characters. Even searching at the risk of his own life and his own mental health and his own fortune, not that he has one, he says, my unchanged love is with my darling child, clearly a Christ figure. And then he says, and I forgive her.

Now one of the themes that ties together my two books, The Crucifixion and Advent, is the subject that you have just brought up, justification as rectification, and the word rectification meaning, essentially, to make right what has been wrong. Now in the case of the girl in David Copperfield, the action of the young man in seducing her with absolutely no concern for her welfare or for her family and her own weakness and vulnerability in falling for his seductive and very underhanded and really wicked ways. All of this reverberates through many, many families and has multiple effects, which reminds me so much of Garrison Keeler's now well-known reflection about a man who is about to leave his wife.

And as I recall it, he is sitting out in front of his house, maybe waiting to be picked up. I'm not sure, I don't remember the details, but I know that he is positioned in his neighborhood, on his street, as he prepares to abandon his family. And he has this image in his mind of a little girl in a neighboring house, upsetting her glass of milk. And he connects that directly with his own action and he decides not to leave because he sees the reverberations of such an action throughout his community and its effect even on the youngest members of the community. A lot of people have been much struck by that reference, almost an offhand reference that Garrison Keeler made, but I emphasize this because every human act of disruption has ripple effects throughout families and communities forgiveness alone cannot make that right. That's the point I'm driving toward. The uncle in David Copperfield says, I forgive her. And that is very important because he is forgiving her even as he is seeking her out. In direct contrast to John Wayne, who is seeking his niece throughout the West, but has not forgiven her and is storing up anger in his heart throughout the story, leaving him in the famous conclusion, alone outside the door. What I'm driving at here, in case people are wondering, is that God's action in Jesus Christ, his action of righteousness for the justification of the world is more than forgiveness. I want to emphasize that because most people seem to think that the very heart and center of the Christian faith is forgiveness. And that's true, but that's not enough to say. As Reginald Fuller, a very important New Testament professor said 50 years ago, forgiveness is not enough to describe what God does. And you brought up rectification, for which I'm very grateful because I had this so much on my mind in the last couple of weeks as I've been reading. The other book that I'm reading that is directly related to this subject is James Cone's The Cross and the Lynching Tree. I did not know about this book somehow, which is incredible. I can't believe it. Apparently a lot of people didn't know about it either because no one told me I should read it.

All the people who were advising me about my book, The Crucifixion, never mentioned it. I go into a lot of detail about the civil rights movement and racial issues in The Crucifixion. Nobody said, you must read this book. And I'm just really very grieved that the name of the author, James Cohn, who I knew at Union Seminary, his name does not even appear in my index the book does not appear in the bibliography of the crucifixion. This is a major gap. And he points out repeatedly in the book, The Cross and the Lynching Tree, that virtually no white person in the church, no theologian, no biblical scholar, no pastor, no teacher, no writer, no white person linked the cross with the lynching of black people. And that is an appalling fact, apparently.

And it's certainly true of me. I try to, in my book, The Crucifixion, I try to find a contemporary reference, a contemporary form of execution that might be comparable. The electric chair has been mentioned, and I bring that up, but then I say that doesn't do the job. I never even bring up the lynching tree because I never thought of it. I thought of lynching often. I knew about...lynching and I knew about the photographs that were taken and I knew about the crowds that would come out and watch and I knew about the mocking and I knew about the postcard pictures that were passed around. I knew all that but somehow I missed the connection to the crucifixion of Christ. The book The Cross and the Lynching Tree makes this connection, well I start to say at great length, it's not a long book and it's very easy to read so I want to urgently recommend it to everyone. It is a limited book in the sense that it focuses only on one aspect of Jesus' crucifixion. People will complain, well, there's no atonement here. That's true. People will complain that there isn't any doctrine of recapitulation here. That's true, and so forth. It's really, in a sense, not a very theological book. It's a passionate, literate outcry on behalf of James Cone's own community, the Black community.

And I think every white person who is serious about the depth of the problems that we face needs to read this as well as we the fact that we need to read it in order rectify our own imagination. Our failure of imagination. Jim Cone talks a lot about failure of imagination and how the black writers and poets, even the ones who were not religious like W.E.B. Du Bois, who was not a poet, but was a storyteller and of course, a thinker. He, with imagination, repeatedly invokes the crucified Christ in his writings. I didn't know that. I know something about James, about W.E.B. Du Bois. I'm very interested in him because he was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts and raised there. And that's where we have our country hosts. So I'm very keen on W.E.B. Du Bois, but did not realize how frequently he invoked the image of the crucified Christ in his work. So all of this in the long run is about rectification. And rectification is the word that some, not all, but some New Testament scholars now prefer to the word justification because it emphasizes this power of God and the promise of God to make right what has been wrong. And forgiveness can't do that. Forgiveness can create a breakthrough or what we often refer to as healing. But even with healing, the scars are there. The feelings are still there. You don't ever get past them entirely with forgiveness. And the wrong is not righted either. And the damage done to the larger community is not affected in any complete way by the act of forgiveness. Although the act of forgiveness is very, very powerful and often will stop the violence, but it will not rectify what has been wrong.

And so when we think of the word justification in Paul's writing, certainly one of his favorite words, we need to think of it not just as saying, that's all right, I forgive you, it's done away with, you can move on, you are a new person now. All of that is true of forgiveness and true of what is traditionally thought of as justification. But what Ernst Kasemann, the extraordinary New Testament scholar of the 20th century. What he saw that was really rather revolutionary was that righteousness, justification, de kiosu in Greek or de kios in Greek, means the power of God to make right. And that is what is linked to the second coming in the teachings of the scripture about the day of the Lord in the Old Testament. What do you think is the necessary connection between righteousness as something that's declared about us and something that God does in us and in the world? As usual, Jason, you have a way of going right to the heart and clarifying a point that I'm trying to make it in way too much length. That's the distinction. That's the distinction that Kasemann wanted to make. And that's the distinction that his very numerous, what shall I say, not disciples, not followers, but

And those who have been profoundly influenced by Kasemann want to hold on to precisely that distinction that you just made. Justification has been traditionally interpreted, especially in the Lutheran tradition, as what did you say? About us. Yeah, a declaration that we are justified means that we are cleared of our guilt and sin, made new people. This is all very important. I don't want to denigrate it. But it doesn't say everything that needs to be said. It doesn't speak to the power of God for new creation. And new creation means, and I can't help thinking again, of Miroslav Volf here, his book called The End of Memory, where he speaks about how even the memory of evil, sin, death, unrighteousness, wickedness, if you will, maybe we should use the word wicked more often, in a theological sense, even the memory will be gone. That's what justification is capable of. We are not capable of that. We are not capable even in forgiveness of erasing the memory. The memory is still there. It's eating away. Not as much as before the forgiveness, but it's still there. And it recurs involuntarily from time to time and has to be fought down. In Christ, in the justification wrought by God in Christ, Miroslav Volf suggests that even the memory will be erased and all will be made new. How do you feel about the idea of memory being erased? Well, I don't want to oversimplify it. It's complicated. We certainly don't want to. We want the memory of love to be erased, or that the memory of those whom we love, and those whom we did not even know we loved, and those whom we did not love, but now love in the new day, that will not be erased. We're talking here about the corroding and corrosive memory of evil confront this in a dramatic sense. And that's one of the things that people who work with tortured victims have to struggle with, the persistence of the memory of the torture, which flares up unbidden in all kinds of ways. I would like to return to the subject of the Advent season, and to say that I found echoes of its meaning throughout the book, The Cross and the Lynching Tree. It's a motto of the book of the dialectic between faith and doubt, the dialectic between suffering and hope, the dialectic between pain and promise. And those are the themes of Advent. I like to say we have to keep our hands in the air all the time, like the scales of justice balancing one off against the other. He contrasts, for instance, he doesn't contrast, he brings into conversation, into the dialectic, the figures of Job and Jacob. Job on the one hand, Jacob on the other hand. Jacob representing the future and hope and Joe representing protest, protest against the treatment that he has received, which seems to be so unjust. So he, Cone, talks about the struggle of the black community to live with their suffering all the time. And that hasn't changed. Living with it all the time, living with the doubt about whether God even exists all the time. And yet, in an unusually powerful dispensation in the black African-American community, an unusually almost unique character of the Christian faith in the black church, the power of hope. What did Desmond Tutu refer to this in a quotation from I think it's Zachariah, I have a hard time remembering Zachariah versus Zephaniah, but I think it's Zachariah who talks about prisoners of hope. When I first read that biblical passage, that really jumped out at me. Prisoners of hope. We are held by hope in captivity to hope.

In spite of our captivity to bondage, we are also captive to hope. And that meant a lot to Desmond Tutu during his struggle against apartheid. So it really does seem to me that the Black race in general, its particular form of Christian faith is a very Advent faith. And I'm just thinking about all the criticism I'm going to get on Twitter and otherwise about how the cross and the lynching tree is very narrow in its focus in terms of what the crucifixion represents doesn't deal with the various Biblical images in the way that I do in my book about the crucifixion, but I'm gonna push back very hard against that kind of protest, because it represents to me a kind of restriction of the work of Christ on the cross, where we have to fit him into our favorite box, whether it's substitution or penal substitution or Christus Victor or whatever it might be. We seem to want to imprison him in our own take on the subject of the meaning of the cross. And whereas in my book, The Crucifixion, I've tried to expand that as far as I was capable. I also want to say that I want to protest against people excluding voices like James Cone because he does not voice traditional motifs or theories of atonement. I was just wondering how you would recommend preachers preach about racism and the season of Advent in particular. I think it's always best in sermons of this sort to make it concrete. I remember Jim Conant, always protesting that theology was not concrete enough. That was his theme. He used to talk about that all the time. It got a little bit annoying actually. But sermons do need to be concrete. We need to give examples of what we're talking about. And it's not hard to find examples of black people express hope in the midst of hopelessness. It happens all the time. I read it in the newspapers constantly. I've always noticed how the New York Times simply will not quote anything Christian unless it's said by a black person, and then they'll quote it. The name of Jesus Christ is not quoted unless it's a black person talking. And I've got so many examples of that in my files. It's just really striking how they will quote the testimony of a black preacher or a black person who has suffered, and they'll call on the Lord or they'll call on the name of Jesus, the New York Times will quote it. We owe the black church so much, and I think of them particularly in terms of Advent, because whereas they never lose sight of the cross, the suffering Jesus, they also live out every day this dynamic, this dialect between doubt and hope, faith and disbelief between what's going on now and the promise of God. Holding onto the promise and looking for signs that the promise is true is what the Christian life is shaped by. That's Advent. Holding onto the promise, even though all the indicators are to the contrary. That's Advent. But the Advent season with its overpowering note of anticipation and promise by its very nature reveals to us in glimpses, glimpses only, but nevertheless life-sustaining glimpses of the promise making itself known even now, even in the worst situations in the faith of believers.