Revelation 21.1-6, 9-27

On Tuesday, just after Huguenot High’s graduation ceremony at the Altria Theater in Richmond, a friend of mine from high school marked herself safe on social media. Shanea had just survived a mass shooting that killed two and injured several others. All told, seven victims were shot.

There is so much bad news in the world.

On Tuesday Shanea became the fourth person I have known who has been involved in a mass school shooting. One was a cross-country coach in Parkland, Florida. Another was an agriculture student at Virginia Tech. Still another was an undertaker who went to Newtown, Connecticut to put parents’s babies back together for their burials.

Four people I’ve known— it’s easier than the Kevin Bacon game.

I suppose it’s not surprising statistic given that guns are the leading cause of death in America for children and teenagers.

Tuesday was the two hundred and fourth mass shooting this year.

There is so much bad news in the world.

Since 2001, the suicide rate for youth ages ten to nineteen rose by forty percent while hospitalization for self-harm increased by eighty-eight percent. “The kids are not all right,” writes one columnist, “and neither are the adults.” As religious observance has declined, deaths of despair have ticked up sharply across every age cohort and demographic group.

And maybe self-medicating despair is the sanest response to the world.

After all, there is so much bad news.

Sea temperatures are the hottest on record. Siberia is suffering through a heat wave— Siberia. Thanks in no small part to a warming planet, much of Canada burns in a blaze, the wildfires choking much of America with a toxic haze. Sixty-three percent of Democrats believe Republicans are immoral. Seventy-two percent of Republicans believe Democrats are crooked. Majorities in both report that violence against the other might be necessary in the near future, and, if necessary, justified.

There is so much bad news.

Vladimir Putin has stolen sixteen thousand Ukrainian children. Eighteen thousand of those children’s parents have been killed in action. For no real reason.

“We are safe,” my friend posted on Tuesday evening, “but we are not ok.”

There is so much bad news.

Sometimes it seems like bad news is the only news.

Except—

We do have good news: He is risen.

In a world without much of it, we’ve been given good news.

Jesus Christ is risen from the dead.

And on the basis of that good news, we can do what no one else in the world dare. We may make promises about the future. Even better, we may give content to this future. We may describe the future.

We can describe now the not yet future.

Because Jesus lives with death behind him, because Jesus rules from the Father’s right hand, because Jesus will come again, consummating what he has accomplished upon the the cross, the outcome of history will be different than it would be otherwise. And because the one who lives and rules and will return is Jesus, we can make promises about history’s outcome.

We can tell the future. We don’t need even need a crystal ball or tarot cards. We just need three little words: He is risen. Armed with the gospel alone, I can tell your fortune.

Skeptical?

Watch me:

Your future— your destiny, in fact— is inclusion in the triune life.

Your future is Father, Son, Holy Spirit, and you. Your future is inclusion in the triune life by virtue of the Son— that’s the work of baptism— and, just so, incorporation into a perfected human community. The future is Father, Son, Holy Spirit, and you and you and you and you…ad infinitum. This is what Paul straightforwardly says to the Colossians:

“You have died [with Christ, through baptism] and your life right now is hid with Christ in God. When Christ who is your life appears, then you also will appear with him.”

How? Where?

“In glory,” Paul writes.

Because he lives, we can describe tomorrow.

As Luther put it, the future for the baptized is “to have all he is and has.”

Your future is to have all God is and all God has— that’s a good fortune. The promise of the gospel— the promise promises that one day, in the fullness of time, on account of Christ alone, God will include you in his glory. And not just you. Yes, there is much bad news in the world. But your future— the Future, the last future— is to share in the glory of God. That’s The End.

Here’s the rub.

No creature has ever beheld the glory of God. Uzzah, in Second Samuel, brushed up against the glory of God on accident and it struck him dead. Moses had to hide his face in the cleft of a rock when God’s glory passed by him and it still disfigured him.

Hence our future is a glory none can yet see.

Therein lies the paradox.

Because he lives, we may describe tomorrow.

Yet we can only describe what, in our mind’s eye, we are able to see.

And how can we possibly picture what Moses himself was not permitted to glimpse?

The last future that is your future is your inclusion into the eternal life of the three person’d God. Look, it’s hard enough to ponder how God can be three persons yet still one. It’s altogether impossible to riddle out how the Three-Who-Are-One can also accommodate an infinite number of Jesus’s friends into their everlasting life.

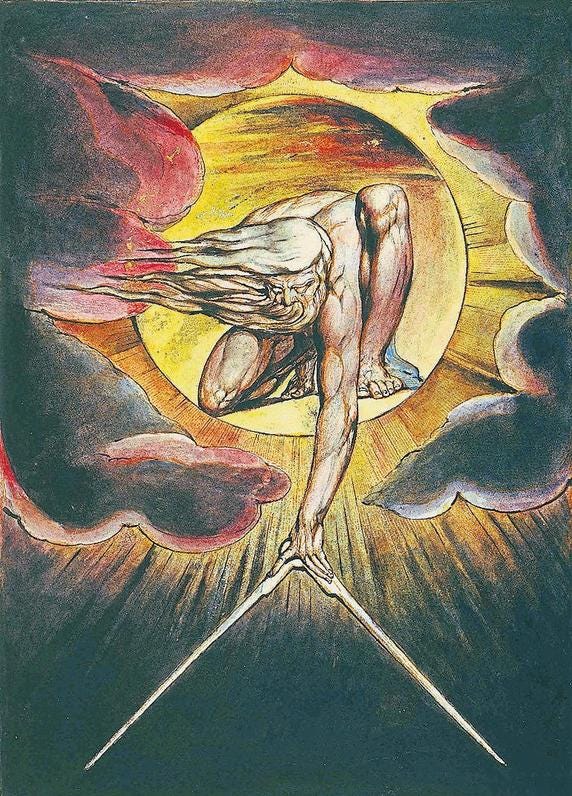

Can A.I. even generate an image for it?

How do you paint a picture of such a promise? How do you imagine what is, by definition, inconceivable? How do you describe what is, essentially, ungraspable?

“All things are yours. And you are Christ’s. And Christ is God’s. This is the Fulfillment,” the ancient church father Basil says.

Says.

How do you see it?

Because he lives indeed, we can tell the future, but how do we illustrate it?

I remember the first time as a rookie pastor someone asked me to sketch a picture of the last future. You know how the phone tree works. Someone in my little congregation in New Jersey knew someone whose child had just been in a car accident, someone who had faith but, for whatever reason, no church home. I know you all think I’m contrary, but I tend to do what I’m asked to do and so about fifteen minutes after getting the call I hustled off campus and drove the ten short miles to Princeton Hospital.

Darrien was a senior in high school. When I got there I saw that his dark skin was broken across his temple. They were a poor family with little money and no airbag.

There is so much bad news in the world.

The ER stall was filled with family members and hospital staff whose laggard motions told me it was just a matter of time. I prayed. I held his mother’s hand when I wasn’t letting her cling to me like a rescue buoy. kept vigil with them.

As Darrien’s time ran out, I squatted down next to him and prayed the Lord’s Prayer into his busted, bloody ear. When I got to the petition asking for earth to be made like heaven, his mom interrupted my piety and asked me:

“What’s it like? Heaven? The Kingdom? I never thought much about it before, but now I need to know. I need to see it.”

I looked up at her and realized it wasn’t a rhetorical question.

She wanted to know.

So I answered her in my way wise and pastoral way, “Uh…”

I fumbled it.

Fortunately, an old man I took to be Darrien’s grandpa rescued me. He let go of the hand clasping his hand. He wiped his eyes. He sucked at his teeth like he was about to spit. And then he nodded his head and he said:

“Whatever heaven is, it sure as hell it ain’t this.”

Whatever heaven is, it sure as hell it ain’t this.

I looked up at him. My knees were tight and sore from squatting next to Darrien’s bed like a catcher behind home plate.

“That’s exactly it,” I said, It’s the opposite of all this.”

I looked over to Darrien’s mother. She nodded almost imperceptibly. The small promise was somehow sufficient for her.

Whatever heaven is, it sure as hell it ain’t this.

He said.

That’s exactly it; it’s the opposite of all this.

I said.

At the time, I had no idea how right we both were.

Near the end of the first century, when the John the Beloved Disciple— the disciple to whom Jesus entrusted his mother— is an old man on the prison island of Patmos, put there by Rome during a period of imperial persecution, the Holy Spirit— the Spirit of Jesus— carries John up into a series of cycles of prophetic visions. This last vision is the conclusive vision. We begin at the end, therefore, because the prior visions have their meaning only in relation to this End. Because what the Spirit of Jesus gives John to see is inconceivable, the Spirit reveals to John using the only Bible the apostles knew; that is, the scriptures of Israel.

Revelation is simply the Latin translation for the Greek word John himself uses, Apocalypse, which means not cataclysm but simply “unveiling.”

The Unveiling to John is perhaps the best title for the book at the back your Bible.

And the Spirit unveils to the seer using a frenzied pastiche of patterns and pictures and promises from the Old Testament. It’s arguably the most Jewish book of the New Testament, and it’s on those terms that it demands to be heard. And— no less than Romans or Mark— the ear is exactly the means by which John intends you to receive it. It’s addressed to seven specific churches; thus, John’s Apocalypse not meant to be an impregnable puzzle. John expects you to grasp it even as the visions unveiled to him grab ahold of you.

It’s scripture— no less than Exodus or Ephesians. It’s scripture so it is not set forth to provide a happy hunting ground for people with pet theories about present day politics and precise timetables concerning the End. There is too much bad news in the world to get this good news wrong. When it comes to John’s Apocalypse, leave Left Behind behind. John’s Apocalypse is scripture, and, as scripture, its subject is absolutely none other than the God of the Gospel. About scripture, the church father Origen compares the books of the Bible to the many locked rooms of a house. Origen writes,

“My Hebrew teachers said that the whole divinely inspired Scripture may be likened to many locked rooms in our house. By each room is placed a key, but not the one that corresponds to it, so that the keys are scattered about beside the rooms, none of them matching the room by which it is placed. It is a difficult task to find the keys and match them to the rooms that they can open. We therefore know the Scriptures that are obscure only by taking the points of departure for understanding them from another place because they have their interpretative principle scattered among them.”

The keys that unlock the room called Revelation are keys labeled Ezekiel and Daniel, Isaiah and Genesis, and Jesus’s own apocalyptic preaching.

Thus, note how the first portion of this final vision describes the New Jerusalem by what is absent from it. “Death will be no more,” John hears the Spirit say, “mourning and crying and pain will be no more.” The sea, the biblical symbol for chaos, will be no more. The church of John’s day, the church under the thumb of Nero and Domitian, had been beset by the mourning and crying and pain and death that persecution occasioned. Thus, this promise to John.

Whatever heaven is, it sure as hell it ain’t this.

And the form of this promise follows a pattern throughout Israel’s scriptures. The prophet Isaiah, for example, abides by the same pattern when he prophesies the coming of Christ. In the future, Isaiah declares in a text we read during Advent, the presence of the messiah will mean the absence of violence and destruction. Why? Because Israel’s history was one long history of suffering invasions and exiles. “They will not hurt or destroy on all my holy mountain,” the Spirit promises the prophet. The Spirit that spoke to Isaiah follows the same pattern with the Beloved Disciple.

Mourning and crying and pain will be no more forever.

In scripture, the promise of the future is always the negation of the present.

School shootings will be no more.

Salvation is always the contrary of already experienced damnation.

What scripture gives humanity to hope for ultimately is always what humanity lacks presently. The new creation is the inversion of this old world with so much bad news in it.

I remember, over twenty years ago now, I was working in the mailroom at

Princeton before my late-morning class. My supervisor, Vince, was on the phone with his wife, who was in the hospital dying of cancer. She told him to find a television and then, he said, the line went dead. The nearest television that September morning was mounted in the corner outside the dining hall. The TV was on mute. And for a while all of us standing there, staring up at the buildings, we were on mute too.

Until the first tower fell and the silence became a chorus of whispered “Oh my Gods.”

The first time I preached was the sermon for the following Sunday. I’d just been appointed by a bishop who was desperate to fill a vacancy at a small, clergy-killing church and who had scoured the seminary for a United Methodist student. I made the mistake of trying to say too much in my sermon that Sunday, as though God needed defending.

Fred was a quiet, elderly African American who served as the patriarch of the congregation. I didn’t know it at the time. Fred’s son always attended service with his Father, but Fred sat alone that Sunday after the eleventh and every Sunday thereafter. His son’s office had been in the second tower.

Just a few weeks later, I was making my way from a coffee shop to campus and I stumbled upon Fred standing in a crowd on Nassau Square. Fred was holding a sign that had a wooden paint-stirrer taped to the back.

The sign was sky blue and in a bold white font it read, “Christians Against War.”

“I didn’t peg you for the protesting type,” I said to him.

And he looked at me with an intensity that unnerved me.

“I’m clinging to the hope I’ll see my boy again,” he said to me.

I looked around at the demonstration, wondering how what he said explained what he was doing.

“I saw the notice for this gathering, and I figured, if the future is Jesus, if the kingdom and the king are one and the same, then if I want to see my boy again, I ought to get more acquainted with Jesus today.”

The future is Jesus.

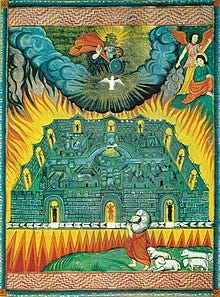

Notice how the Beloved Disciple’s language shifts as he attempts to describe what the Spirit had showed him. The New Jerusalem that is the new creation is a city but by the next verse it’s a bride and in the verse after that it’s the tabernacle that had traveled alongside the Israelites during their exodus. Then in the final portion of this last vision, the Spirit of Jesus carries John up to a great, high mountain and shows him a vision of the New Jerusalem similar the vision the Spirit had shown the prophet Ezekiel. The city is adorned with twelve jewels. It rests on twelve foundations and twelve gates encompass it. Its length is the same as its width, measuring 12,0000 stadia in every direction.

That’s 1,500 miles in every direction.

That’s a freaking big city.

That’s— not coincidentally— the breadth of Nero’s empire.

In every direction.

The details are dizzying.

Jasper and onyx and pearls.

Cornelian and amethyst and beryl (whatever that is).

It’s a kaleidoscopic, seizure-inducing array of Old Testament images. One after another after another after another.

But their sum is simpler than their number. For they all merely add up to the four words Fred told me on Nassau Street those many years ago.

The future is Jesus.

Don’t believe me?

It’s right there in the details.

The City of God, the Lamb’s Bride— notice— it’s a perfect cube. “It lies foursquare,’ John reports, “its length the same as its width.”

A perfect cube— just like the Holy of Holies, the inner sanctum of the Jerusalem temple, the dwelling place of God.

A perfect cube— just like the Holy of Holies, made absurdly and unimaginably bigger so as to accommodate those who have been made heirs with the Father’s only Son through water and the Spirit.

John’s Apocalypse—

It’s not a secret cipher to be decoded so that we can predict the future.

It’s scripture.

It’s aim is none other than to point to the Triune God's primal promise, “I will be your God and you will be my people.”

On Tuesday, across the street from the Altria Theater in Richmond, dropped diplomas and abandoned caps and gowns and tassels littered the grounds of Monroe Park. In the immediate, chaotic aftermath of the Huguenot High shooting, a car whose driver was simply attempting to escape danger struck a nine year old who had gotten lost in the melee.

For a time on Tuesday, my friend couldn’t find her son, Parker. He has no cell phone so they couldn’t contact him. “Until we found him hiding in the theater,” she said, “panic and prayers were all we had. We feared the worst.”

And why shouldn’t she fear the worst? Why should any of us not expect the worst? There is so much bad news in the world. As Paul says simply but bravely, if this world is all there is, we ought to be pitied.

Fortunately—

Because Jesus lives, his old friend John can describe tomorrow.

And like an artist armed with a portfolio of pictures, John’s here to show us.

A better world is on the way.

Share this post