Genesis 29.1-30

Rebekah’s fidelity to the strange promise she received from the Lord leads to her youngest child’s exile. On account of God’s promise, Jacob has dishonored his father and stolen his elder brother’s blessing. Esau consoled himself, scripture says, by plotting to kill his brother. Thus, Jacob is a refugee from home, headed eastward, hoping to find sanctuary in the country of his mother’s kin.

He discovers that he’s reached his destination when he encounters a trio of shepherds who inform him that he’s arrived in Haran. Initially, Genesis reports an unremarkable, leisurely exchange between strangers at a watering hole.

“My brothers, where do you come from?”

“We are from Haran.”

“Do you know my uncle, Laban son of Nahor?”

“We do.”

“Is it well with him?”

“Yes, and here is his daughter, Rachel, coming with the flock.”

Then it happens.

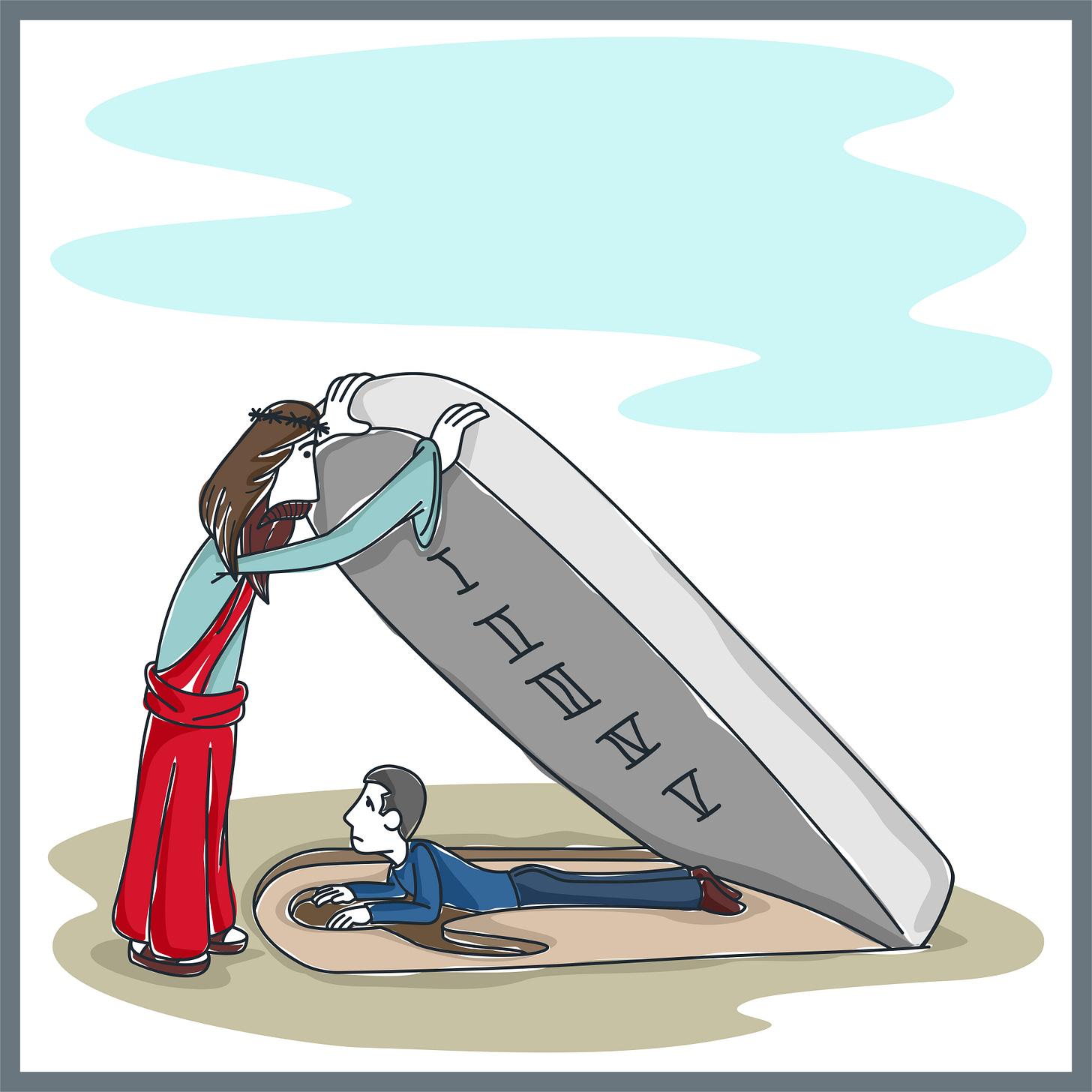

Over the horizon, Jacob sees Rachel. And he’s allured, aroused, overcome. He’s so captivated by the sight of her, so bewitched and enchanted by her beauty, the urgency of desire galvanizes him. You think Mark, the Cue Card Guy, in Love Actually made a bold move? Rachel hasn’t even had him at hello yet. Jacob simply sees Rachel and immediately Jacob turns to pick up the heavy stone sitting like a lid on the mouth of the well and he does what the three shepherds by themselves could not do. He rolls the stone away. Love not only conquers death, it compels lovers to offer extravagant, even silly gestures.

Jacob sees Rachel, and he rolls the stone away, as if it’s the most sensical response imaginable. And then, as foolish as meeting a stranger at the top of the Empire State Building, Jacob kisses her and, in kissing her, he’s so overwhelmed by passion for her that he starts to weep.

Jacob asks Laban permission to betroth her a month later.

Jacob labors under Laban for seven years in order to wed her.

It’s a strange story.

At the end of his prolonged betrothal, Jacob attempts to consummate his pledge to Rachel. They don’t teach this part of the story in Godly Play. There’s a wedding party. In the tradition of Christ at Cana, Jacob evidently has a few drinks more than he should, and his groomsmen must be too over-served to watch out for their friend. Jacob goes to Rachel in the honeymoon suite.

The lights must have been off.

In the morning, Jacob rolls over in bed and, in my favorite bit of biblical understatement, Genesis says simply, “It was Leah!” The meet-cute at a well trope aside, it’s not a conventional, happily ever after love story. Nevertheless, in the end, Jacob gets the girl, but in the process he gets a lot more than he anticipated, a second wife whom he doesn’t find nearly as attractive or alluring and seven more years of labor under Laban’s thumb.

It’s a strange story made stranger still by the fact its scripture.

Think about it— this meet-cute at a well is canon. It’s not Ovid or Arabian Nights. It’s the Word of the Lord.

And because God is the Word, this strange story is God’s self-revelation.

Jacob’s urgent desire and foolhardy gestures and unreasonable commitment— fourteen years he labored to love her— are revelatory not simply of Jacob but of Jacob’s God, the God of Israel. Just as surely as he does atop Mt. Sinai or in Mary’s womb, the Triune God reveals something of himself in this odd, embarrassing, and erotic story. Were it not so, this story would not be counted among the canon.

This past May a friend and clergy colleague celebrated his tenth anniversary. He asked me to officiate a service for the renewal of their vows and to preach at that service. Because most of his attention was given to the afterparty at a local brewery, he left the selection of a scripture text to me— obviously a mistake. Leave it up me and I’ll choose 1 Corinthians 13, with its pablum about love being patient and kind, never out of ten times. Instead I chose this passage from Genesis that narrates Jacob’s urgent and unchecked and unwise passion.

“This story is the story of every marriage,” I told them in my sermon.

“This odd story is the story of every couple crazy enough to pledge “I do” to the stranger whom they love. One day you wake up, and you expect to find Rachel, the person that made you say and do things you never thought you’d do or say, the person who you dreamed dreams about and dreamed dreams with, and what do you find, Leah. Someone strangely unfamiliar. The fact is that you married both of these people. You married their best self— their Rachel— and their shadow side— Leah. The key to showing forgiveness and grace in marriage is to understand that we all bring a Rachel and a Leah to every one of our relationships. We all have a lovely and an unlovely side to our selves. The key to a merciful marriage is learning how to love both the Rachel and the Leah to whom you’re married.”

I preached.

And what I said about relationships is true. What I said about relationships is even, more or less, a clear implication of the gospel. What’s more, what I said about relationships— I know, people tell me— it’s actually helpful. Nevertheless, this narrative of Jacob’s embarrassing and extravagant eros is not in scripture so that preachers like me can offer advice to people like you. We may be able to glean wisdom about our relationships with one another from this narrative but Jacob’s passionate and foolhardy pursuit of Rachel is not canon because it illuminates our relationships with one another. As Robert Jenson writes,

“If we make the Bible a collection of tales about a fanciful other world, it will have no power, and if we make the Bible a source of advice about how to get along in the world, the advice will always prove unsuitable and will again have no power. But we will do one or the other if we do not with every glance into the book confess the Christ of Nicaea and Chalcedon. What scripture opens to us is the mystery of Christ. And our preaching and teaching and reading from scripture will have power as— and only as— the mystery of Christ is at every biblical step what we discover in the Bible and preach and teach and obey.”

What Jenson writes about scripture is no different than what Jesus himself says of it on Easter. Walking along the way to Emmaus, Luke reports the Risen Christ “interpreted to [Cleopas and the other disciple] all the things about himself in all of the scriptures, beginning with Moses [that’s the Book of Genesis] and all the prophets.” Straight out of the grave, what Jesus wants his disciples to know is that the whole of Israel’s scriptures are about him.

Like Jesus burning and aglow with the glory of God on the Mount of Transfiguration, all of scripture is an epiphany.

It’s all Christophany.

It all shimmers and glistens with the mystery of the Triune God.

It’s not “The Old Testament is over there and the New Testament is over here and the two are radically distinct from one another.” No, that’s an ancient heresy called Marcionism. All of it, all of scripture— its purpose, Jesus teaches— is to disclose the Father’s only Son to his beloved. The purpose of the passage in Genesis 29, therefore, is not as a prooftext for “practical” Christianity. Rather, Jacob’s romantic comedy was recorded in Israel’s scripture and later included in the Christian Bible because it is revelatory. It unveils the true God’s love for his people.

If the claim made on the way to Emmaus is true (and if it’s not true, we have no basis for our faith), if all the scriptures disclose the Lord Jesus, if every passage of the Bible points in some way to the Father’s Son and their love for their people, then we are supposed to see Jacob as more than merely Isaac’s son and we are meant to recognize that Rachel is not simply the object of his fierce and urgent desire.

Jacob signifies the Almighty Father’s only begotten Son.

And Rachel represents you.

You are Rachel.

You are this fierce and foolish Lover’s delight.

To the old rabbis, this much was clear. One of those ancient interpreters went so far as to assert that “anyone who says this is just a love story forfeits his share in the world to come.” According to the ancient church fathers, the lovers in this meet-cute at a well are Christ and the Church or, therein, Christ and the believing soul. And this is not an allegorical reading of scripture. This is the plain sense of scripture precisely because this is the very reason Israel and later the Church included this scripture in the canon. Straightforwardly, the Lord Jesus Christ is here cast as Jacob. And you are Rachel. You are the occasion for his ridiculous wooing, his uncontrollable kisses and astonished tears, his extravagant and costly patience.

Years ago, I buried an old woman in my parish named Paige. She had no children. So far as I knew, Paige had never married. Her family had all predeceased her. To be honest, I had always pictured Paige as a spinster, old and lonely, with not much in her life but a fat orange cat and some friends in the choir. One of those choir friends, Betty, ended up being the one to settle Paige’s estate when she died. No sooner had she started to clean out Paige’s modest home than she rushed into my office to tell me.

“I couldn’t believe it. You’ll never believe it,” she said, truly astonished.

“Believe what?” I asked, expecting to hear she’d discovered a dozen more cats in the deceased’s house.

“I found all these photos,” she said breathlessly, “and love letters, boxes of them, stacks tied with ribbon.”

“Really,” I said, “photos with whom? Letters from whom?”

“Stuart,” she said, “before he died.”

“Stuart,” I said and I paused, thinking, “you mean from the choir?”

She nodded and then shook her head at the mystery of it.

“I’d seen them chatting before worship,” I said, “but I had no idea.”

“Neither did I. Not a clue.”

“She didn’t get rid of them,” I said, “She wanted you to find them. She wanted you to know. It’s like the Holy Spirit— love between two needs a third person, a witness.”

“You think so?”

I nodded and then I said, “Well, gosh. We’ve got to share that story during the funeral. She had a love in her life no one suspected. We’ve got to celebrate it.”

“No,” Betty waved me off, “We can’t tell. It wouldn’t be appropriate to share about Stuart and her at a funeral of all places.”

“Appropriate?” I said, “It’s more than appropriate. A love affair is the perfect analogy for how Paige is now loved by her God.”

Betty squinted at me, uncomfortable I could tell, with Paige being paired with the Lord in such carnal terms, but it’s nothing short of biblical.

There’s a reason why falling in love makes us all like the burning bush, ablaze with glory but somehow not consumed by it. It is because there is no other experience in our lives that so closely approximates how God loves God and, correlatively, how God loves you.

Notice how the Book of Genesis is entirely uncritical of Jacob’s impetuous passion.

When it comes to the urgency of Jacob’s desire, scripture offers nary a hint of reproach.

This is but another reminder of how odd is the God of the Bible. By contrast, Plato wished to ban poets and songwriters from his Republic because he thought their ability to arouse emotion and kindle passion was at odds with the virtues. Passion was dangerous, Plato believed, the very opposite of prudence and wisdom. Along with Plato and much like the Buddhists, the ancient Greek philosophers saw cool rationality and emotional detachment as the center of human dignity and, thus, as the essence of true religion.

Not so the God of Israel.

Quite simply, Israel experienced the favor of her God as his burning, unquenchable, passionate love for her. The Book of Deuteronomy insists upon it as a matter of dogma. The Lord chose Israel not because Israel was the greatest among the nations. The Lord chose Israel not because Israel had a particular proclivity for covenant or unique potential for faithfulness. The Lord chose Israel and made her his own for no other reason than that the Lord loved her. Israel’s election, her chosenness, is the result neither of a rational decision nor an arbitrary one.

God is the God of Israel because the Lord fell in love with her.

Just as God happens in the world, Israel happens to God.

And he falls in love with her.

And it’s every bit as foolish and impulsive as the love Rachel arouses in Jacob, for God’s People, then and now, in no way warrant such steadfast passion nor are we reliably monogamous lovers.

Lovers—

The analogy between the Lord’s relationship to Israel and conjugal love shows up early and often in scripture. “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth,” Israel sings in scripture before turning to the Lord and inviting him to her, “Draw me after you, let us make haste…” Not only is Israel’s Lord a Lover, he is a covetous one. The Lord tells Moses on Mt. Sinai that Jealous (with a capital J) is the Lord’s proper name. The prophets, meanwhile, seize upon the underside of this analogy and rail against Israel as the Lord’s “whoring bride.”

This marital analogy is not unique to Israel’s scripture. “This is my body. I give it to you,” the earliest Christians recognized from the start that Christ’s words of institution at the eucharist are simultaneously the words of a lover to his beloved, a connection made even more unavoidable when we eat and drink and thereby take the Lover’s body in to our own bodies. In his letter to the Ephesians, the apostle Paul interprets the mystery of sexual union by relation of Christ and the Church and by relation to the triune life itself.

And note what Paul thereby stipulates. According to the logic of analogy, the love shared between human lovers is recognizably passionate only by distant resemblance to a true passion which is God's alone. Our passion is the copy of a copy of a copy of a copy. Of which God’s passion is the original.

Very few of us would roll away a stone, kiss and weep and ask for an “I do” before we even said hello or got together for drinks. Our passion is faint and faded compared to the passion of the Triune God.

Passion.

Eros.

In 1930, the Swedish Protestant theologian Anders Nygren published an enormously influential book entitled, Agape and Eros. Agape and eros, Nygren argued, are opposite phenomenon which nevertheless get translated into English with the same word, “love.” Agape, Nygren posited, is disinterested self-giving love to the other while eros is needy desire for the other. The God of the Bible, according to Nygren, is all agape and no eros, and, by implication God’s people should likewise strive for the former and renounce the latter. Nygren’s argument was successful just to the extent that most people of faith aspire to agape love while talk of erotic love seems embarrassingly out of place in worship.

As common as it is to draw a distinction between agape and eros, it’s wrongheaded. No straightforward reading of scripture can agree with it. “My beloved is a packet of myrrh, lodged between my breasts,” Israel sings of God in scripture. That’s plainly unabashed, unashamed eros not agape. Besides, who on earth ever would want to be loved only with a disinterested, self-giving love? Who on earth would want to be the object of someone’s charity instead of the object of their passionate delight and overwhelming desire? Not only will the biblical narrative not support a distinction between supposedly divine agape and fleshly eros, the very name of God rules it out.

Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

The Father would not be the Father without the Son.

The Son would not be the Son without the Father.

The Holy Spirit would not be except as the bond of love between the two.

In other words, the name of God itself insists that the Father needs the Son to be God. The Son needs the Father to be God. The Holy Spirit needs the Father to love the Son and the Son to love the Father for the Holy Spirit to be God. Therefore, the attributes of eros— need, want, desire, longing— are not antithetical to God’s love. As Robert Jenson writes, they belong to the very being of God.”

Need, want, desire, longing belong to the very being of the Triune God.

In his memoir Mortal Lessons: Notes on the Art of Surgery, Richard Selzer tells of a young woman, a new wife, from whose face he removed a tumor, cutting a nerve in her cheek in the process and leaving her face smiling in a twisted palsy.

Her young husband stood by the bed as she awoke and appraised her new self, “Will my mouth always be like this?” she asks.

The surgeon nods and her husband smiles, “I like it,” he says, “It is kind of cute.”

Selzer goes one to testify to the epiphany he witnesses:

“Unmindful, he bends to kiss her crooked mouth, and I’m so close I can see how he twists his own lips to accommodate to hers, to show her that their kiss still works. And all at once, I know who he is. I understand, and I lower my gaze and back away slowly. One is not bold in an encounter with God.”

Selzer, the surgeon, knew more than Nygren, the theologian.

The theologian should know better.

The apostle Paul presents discipleship not as climbing a ladder to God, one rung up and two rungs down ever after. Paul presents discipleship neither as a process of accruing righteousness nor as a process of becoming a better you. Paul does not even present discipleship as the path of an apprentice following after a master teacher.

Paul presents discipleship as courtship.

As a courtship that cannot fail.

“I promised you in marriage,” Paul writes to the Corinthians, “I promised you in marriage to one husband, to present you as a chaste virgin to Christ.”

For Paul, discipleship is not about learning or serving or improving. For Paul, discipleship is not about piety; it’s about passion.

Discipleship is about being woo’d.

Courted.

Seduced.

And of course discipleship is about being woo’d— what the English Reformation called “divine allurement.”

If the consumption that all of scripture is driving towards— the very conclusion of the Bible— is what the Book of Revelation calls the Marriage Supper of the Lamb, then, absolutely, more so than a forgiver or redeemer, more so than a shepherd or a sage or, even, a sacrifice, more so than our maker or our judge, the Lord God is our Lover. The God of the Bible is very much— more so than any other possible image— like a Lover who stoops down and contorts his lips, so badly does he long for his beloved’s kiss.

The Lord is a Lover.

And you are his Rachel.

He gives you his very body so that your heart might be crucified by his love.

And just to get your attention, just to woo you— on the third day, he picked up the stone and he rolled it away.

So come to the table. As John Wesley says, the table is our altar call. Why would you invite the Lord into your heart when he wants to enter you all the way down? Come to the table, and, to the one who labors still, patiently and ceaselessly, in word and water and wine and bread, to woo you, give him your hand.

And say, “I do.”

Share this post