Holy Thursday — Exodus 12.1-14

On the night he’s handed over, as the host of his last Passover, Jesus doesn’t just change the script (“This is my body” rather than “This is the body of the passover”) Jesus adds to it. According to the Haggadah, after they feast on the meal, Jesus is supposed to pour and bless the third cup of wine, and invite the disciples to drink it. Then, according to the script, they’re supposed to sing from the Book of Psalms before blessing and drinking the fourth cup of wine. Except, after they feast on the meal, when the time comes, Jesus takes the third cup of wine, the cup symbolizing God’s redemption promise (“I will deliver you from captivity”) and Jesus says, “This is my blood…drink from this all of you…”

Hang on— drink what?

What’s blood doing on our table?

They’d be better off going back to eating and drinking with hookers and thieves. Blood shouldn’t be anywhere near their table. The law stipulated that "anyone of the house of Israel who eats any blood, I the Lord will set my face against that person who consumes blood, and will forsake that person as accursed…”

Blood is forbidden.

Anyone who consumes it in any way is accursed. That’s why verse nine in Exodus 12 commands Israel to roast the Passover lamb over a fire not boil it or consume it raw. None of the blood of the lamb can end up on the table. And this isn’t an arbitrary law designed to bless the world with Jewish delis and kosher hot dogs.

Blood was forbidden because blood symbolized life.

As such, the blood belonged to the Giver of Life alone. Blood can’t be on your menu because it’s not yours to serve. And because God is the giver of life to every creature the blood of every creature, in fact, represents God’s own life. But now, Jesus is once again breaking the law of the covenant by inviting them to drink it, “Drink from this all of you. This is my blood of the new covenant poured out for you and for many for deliverance from sins.”

According to the law, the blood on the table makes him forsaken.

Which is to say, to obey him and drink his blood is to disobey the law in league with him and thus to share in his forsakenness. To obey him is to share in the curse he will bear. To be crucified with him. He’s offering them what belongs to God alone. He’s offering them his life. Which is to say, he’s offering them his death. He’s offering them a share in his death.

“This is my blood of the new covenant poured out for you and for many for the deliverance from sins.”

Not only should the blood of the lamb not be in the third cup or even on the Passover table at all, what’s left of the lamb’s blood Jesus should’ve smeared across the door to the upper room. The blood-smeared door will a sign, God promises; so that, when God’s angel of Death passes over, God’s people will be spared the wages of Pharaoh’s sin.

The blood— it will be a sign, God promises.

But hold up— God doesn’t need a sign!

The Almighty from whom no secret is hid does not need an SOS streaked in neon blood. In all of Midian, God managed to find Moses and meet him in a burning bush. God doesn’t need a sign like the Bat Signal to find his People.

No.

From God’s side, the blood is superfluous.

From God’s side, the blood is absolutely unnecessary.

God doesn’t need a sign. We do.

We need something tangible and visible in which to place our faith.

We need something outside of ourselves to believe.

In his book The Preached God, the theologian Gerhard Forde recalls a seminary student for whom he served as an advisor. Returning to campus from the summer hiatus, the seminarian told her professor how during the course of her internship she had engaged the film-maker Woody Allen in a number of extensive and interesting conversations. Apparently the congregation where the seminarian had served during the summer owned the house next to the church, and Woody Allen had leased the house as the set for his forthcoming movie.

Having befriended the director, their conversations soon got around to theology. The seminarian shared her surprise with her professor that she had discovered that Allen was a fairly astute student of theology. He even recommended books to her, authors and biblical commentaries.

One day the film-maker said to the seminarian, “You know, I would like to believe in God. I would like to encounter God. But I don’t have the gift of faith.”

The professor listened to his student’s story and quickly interrupted her, “Aha! You hooked him! What did you say then?”

The student confessed her failure honestly, “I didn’t know what to say. He knew as much theology as I did. How was I going to convince him of God? Get him to faith? What was I supposed to say?”

After thinking about it, the professor replied to her:

“Well, suppose you could have said something like this: ‘Is this for real and not just idle chit-chat? Is this a confession? You would like to believe in God— be encountered by him— but you don’t have the gift of faith? Well, hang on to your socks because I am about to give both God and faith to you in one fell swoop!’

And then you put your hand on his head and say, ‘I declare unto you the gracious forgiveness of all your sins in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. There! Now I gave it to you, God and faith in him! Just as sure as you sensed my extended hand they are both now yours. Repent and believe it. And if you ever wonder about it or forget it, come back and I’ll do it again. Better yet, come to church. God shows up every Sunday and hands over faith in edible form. I can even wash you in God.’”

As the Large Catechism puts it, faith must have something concrete to believe, something to which it may cling and upon which it can stand. This is why Martin Luther insisted that the sacraments and faith should never be separated. Your faith must have something external to you to grab onto and cling to for life. Otherwise, faith turns inward and you're left attempting to have faith in your faith.

No one's faith is so strong.

Indeed for the first Protestants the phrase “by faith alone” could just as easily be substituted as “by bread and wine alone” or “by loaf and cup alone” or “by water and the word alone” because it's on sacramental faith that we stand.

What is sacramental faith?

Sacramental faith is the conviction that the gospel is not a once upon a time story about an event that happened in a Galilee far, far away.

Rather sacramental faith is the conviction that the living God acts in the here and now to reclaim the lost, that he comes to us extra nos, from outside of us, an alien word attached to creatures like water, wine, and bread.

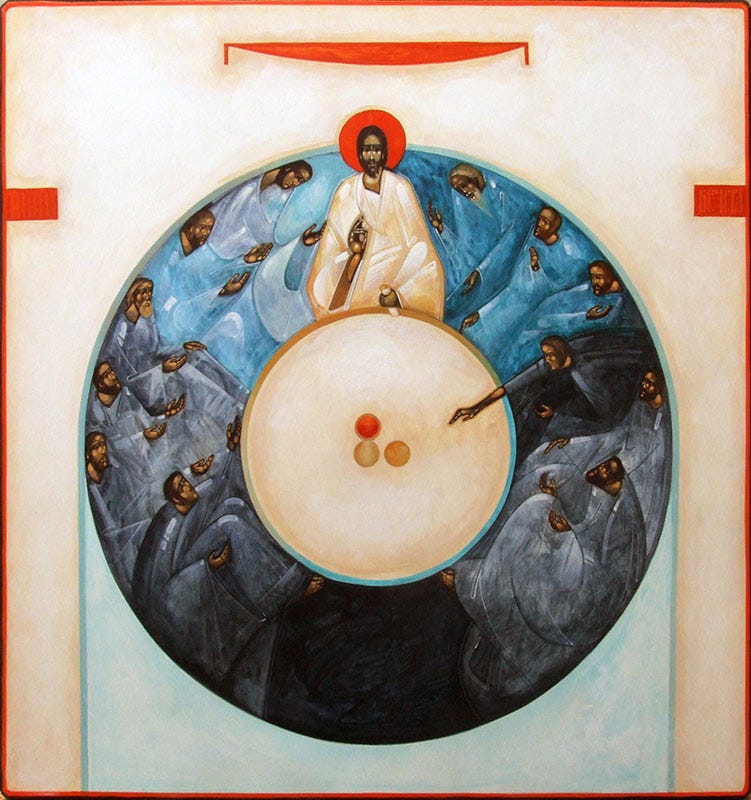

In several places, the New Testament Book of Hebrews proclaims that Jesus is our great high priest, “a priest according to the order of Melchizedek.” Just after the flood, in the Book of Genesis, when he is still in the infancy of his election, Abram encounters a figure named Melchizedek, who is both a king and a priest. Melchizedek goes out to meet Abram. And Melchizedek takes with him bread and wine. In the name of the Most High God, Melchizedek blesses the bread and the wine, and he gives it to Abram, saying, “bless be Abram by God Most High, maker of heaven and earth, and blessed be God Most High.”

And there in the valley with the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah behind him, Abram takes the bread and the wine. And he eats the bread and he drinks the wine. And he tastes and sees the promise of the blessing of the Most High God. He grabs hold of it in his hands. And here and now.

Christ Jesus is a priest like Melchizedek, says the book of Hebrews.

Like Melchizedek, Christ comes down and meets us in the valley of the shadow of death, and Christ gives us wine and bread to which we can cling. Like Melchizedek, Christ gives us tangible, visible means which we can grab ahold of and know, in the here and now that, as Gerhard Forde says, “the one who runs the whole show is for you.” Without these external things, faith has nothing to believe but some incomprehensible promise about the distant future or some ancient history that happened over two thousand years ago.

We require more.

We need signs.

Faith can only be faith when it has a concrete promise to believe.

After all, even the demons and the pagans believe in the history of Jesus. What the demons and the pagans do not believe is that that history of Jesus is for them. Faith then is not about you believing in God. Faith is not about you believing that two thousand years ago Jesus died for you. It's not even about you believing that three days later God raised him from the dead for your justification.

As Martin Luther proclaimed:

“If I now seek the forgiveness of sins, I do not run to the cross, for I will not find the forgiveness of my sins at the cross, but I will find it in the sacrament. I will find it in the gospel word which distributes, presents, offers, and gives to me today that forgiveness which was won on the cross.”

Thus, Holy Thursday is the day when we recall that faith is an everyday encounter. Faith is an ongoing, living, present-tense, laying hold of the promise that God makes to you in the here and now. Faith is holding out your hands to receive the bread and the wine through which God promises to you— tonight— “the body and blood of my Son given for you.” In other words, the Living God uses bread and wine to promise to you, in the present, that he loves you to the grave and back.

Grace is not cheap. It’s not even expensive.

It's free.

And it's precisely the freeness of the gift that destroys the self that so wishes to stay in control.

In precisely this way, the sacrament sanctifies.

It turns you out of yourself. It turns you inside out. It breaks the self's incurable addiction to itself.

And by doing so, it reverses the very first sin our parents made in paradise.

Therein lies the good news in God giving us the loaf and cup.

As a Christian, you don't need to believe a thousand different things about God.

You don't need to believe in a future you scarcely can imagine.

You don't even need to believe in a two thousand year old history.

You only need to cling to these promises made concrete in bread and wine and water.

“I’ll wash you in him— you could have said something like that,” Professor Forde said to his seminarian about her conversations with the filmmaker.

“But oh,” the student said, “that would take a lot of guts.”

To which her professor replied:

“Of course it takes guts, but in the church we call it the Holy Spirit! Why not, after all, take some chances, give it your best shot? Perhaps the man does not need any more explanations. He has heard them all.

It is the dirtiest trick in the theological arsenal to be everlastingly explaining that justification, faith, and grace are free gifts, but never getting around to giving them: never, that is, moving from explanation to proclamation, never taking the risk of actually handing over the goods!

When faced with doubt — “I don’t have the gift of faith” — shall we explain about God, his love, about how it is a free gift? All that is pure schwärmerei. It leaves the poor man on his own to make peace with an explanation.

When faced with doubt — “I don’t have the gift of faith” — do not explain about God.

Speak for God.

Give God.”

In John’s Gospel, on the night he’s handed over, Jesus gets up from the supper table, he sets aside his robe, and puts on an apron. Then he pours water into a basin, stoops over onto his knees and one-by-one he begins to wash his friends’s dirty feet.

When he gets to Peter, Peter starts arguing, “You're not going to wash my feet-ever!”

And Jesus says, “Unless I wash you, you can't be part of me or my kingdom.”

And Peter replies, “Not only my feet, then. Wash my hands! Wash my head! Wash all of me.”

We forget how the rest of that story goes.

We forget how Jesus promises to Peter and his disciples, “Now, I need only to wash your feet; soon I will make the rest of you clean forever.”

I’ll make the rest of you forever clean.

I’ll make the rest of you forever clean.

It’s an astonishing promise.

The promise is so good it is damn near impossible to believe.

Thankfully, Jesus gives us something concrete, a visible word, in which to put our faith.

He takes the promise of the gospel, attaches it to tangible things, and he gives them a pronoun, “Here, take and eat…drink from this…it’s for you.’

“You know, I would like to believe in God. I would like to encounter God. But I don’t have the gift of faith.”

Maybe the voice in your head sounds an awful lot like Woody Allen. I know the voice in my own head so often sounds like him. If so, come to the table.

The Small Catechism explains the third article of the Apostles’s Creed by saying:

“I believe that I cannot by my own reason or strength believe in Jesus Christ, my Lord, or come to Him; but the Holy Ghost calls me to the gospel…”

Only God can reveal God.

If you’re going to cling to Jesus Christ, the Spirit must summon you to him.

That summons happens here.

That’s why, “I believe in the Holy Spirit” is followed immediately in the dogma by, “I believe in the holy, universal church.” The Spirit calls you to receive faith by means as ordinary as loaf and cup.

This is the gospel:

God is not waiting around for you to clean up your act and find your way to him; God is here— one-way love— waiting for you to receive him.

This is the gate of heaven.

Here, the great silence of eternity is reliably broken.

Here, wearing masks of bread and wine, the true and living triune God says, “You are mine! The one who runs the whole show is for you!”

Share this post