Revelation 14.1-13

In the fall of 1935, the Nazi Regime announced the Nuremberg Race Laws. The first law eliminated from German citizenship all Jews and other non-Aryans. The second law, the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, banned “race-defilement” through mixed marriages and sexual relations. Thus, the Nuremberg Race Laws made the public marking of Jews a necessity.

With staggeringly few exceptions, the churches in Hitler’s Babylon refused to take a public stand against the decrees.

Also by the fall of 1935, the process of Gleichschaltung—the Nazi term for the saturation and coordination of German civic, education, cultural, religious, and political institutions with Nazi ideology—was essentially complete. Under the process of Gleichschaltung, the empire would only consider those churches legal whose pastors agreed to take their theological exams under the authority of a Nazi committee. Again with damningly few exceptions, most churches quickly capitulated to the mandate and accused the few lonely faithful voices in the Confessing Church of preaching politics. This is perhaps the reason why the Nazi regime had largely lost interest in monitoring the church by the fall of 1935.

Put differently—

By the fall of 1935, the church feared Hitler more than she feared her God, who just is the God of the Jews. And no longer fearing God, the church was no longer sufficiently faithful so as to raise the regime’s concern.

Nevertheless!

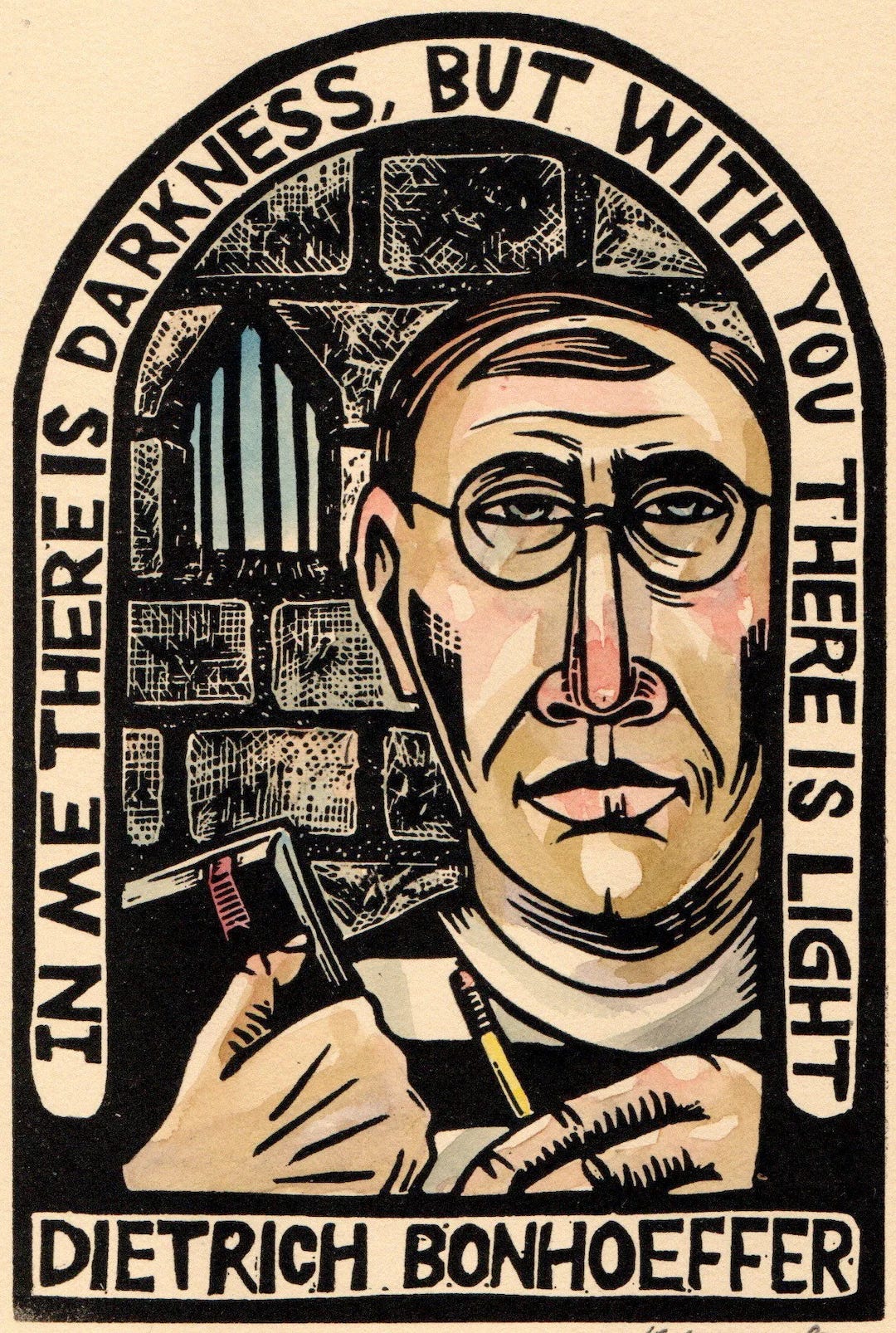

At the same time, at the Confessing Church's underground seminary in Finkenwalde, Germany, on the occasion of Remembrance Day— Germany’s Memorial Day— Dietrich Bonhoeffer preached a remarkably bold sermon. Deviating from the assigned lectionary scriptures for the day, Bonhoeffer chose as his preaching text Revelation 14.6-13.

Bonhoeffer’s hearers were his students.

All of them were frightened.

Many of them were on the precipice of unfaithfulness.

In fact, the Gestapo would soon shutter the Finkenwalde seminary and by the war’s end Bonhoeffer would be martyred on the Führer’s direct order. But in November 1935, on Memorial Day, Bonhoeffer preached on the fourteenth chapter of the Apocalypse and he entitled his sermon, “Standing Strong in Babylon.”

It was one of the few times Bonhoeffer ever made reference in the pulpit to National Socialism.

“What awaits us is not nothing,” Bonhoeffer says the top of his sermon.

The world after death, Bonhoeffer notes, is anything but dead; “indeed, it is quite alive, full of action, visions, words, torments, and bliss—the world after death is actually life to the highest degree.”

This vision of the Last Future is not a spiritual opiate for the masses.

It’s a summons.

“Let us not offer ourselves false comfort,” Bonhoeffer writes, “by insisting that soon it will all be over; instead, we must recognize that, quite the contrary, soon it will all begin, soon things will become quite serious and quite critical for us.”

Just then, in the very beginning of his sermon, Bonhoeffer puts the purpose of the passage bluntly:

“This text wants to help us prepare for that step into the next world. How do Christians, how does the church-community of Christ learn to die? That is the question to which this text offers an answer. This text proclaims a threefold message of joy to us from that world [after death] as consolation on this Remembrance Sunday and as an aid to our own dying.”

The scripture offers a message of comfort exactly to the extent it shows us how to die.

John’s vision shows us how to die in that John sees an angel in between heaven and earth, as though perched in a pulpit, proclaiming “the everlasting gospel.” Even though it may appear at present that the gospel is in demise, the gospel will abide “as the one and only true proclamation of God over all the world.”

Jesus had promised that hell will not prevail against his church.

Now we learn why.

Hell will not prevail against the church because the gospel is eternal, and the angel’s message is the church's mandate.

The everlastingness of the gospel shows us how to die, Bonhoeffer preaches, because it reveals to us the sole basis on which we may assess our lives.

The eventual martyr said to the soon-to-be preachers:

“What will God ask about on that day of judgment toward which we are moving? moving? About God’s eternal gospel: Did you hear and believe the gospel? God will not ask—whether we were great and influential and successful, whether we have a life’s work that can be presented, whether other people respected us, or whether we were small and unimportant and unsuccessful and unappreciated. God will not even ask— whether we were Germans or Jews, whether we were Nazis, or even whether we belonged to the Confessing Church—God will one day ask all human beings whether they believe they can prove themselves before the gospel—and the gospel alone will be our judge. It is the gospel that will separate souls in eternity.”

The gospel is everlasting.

This is critical for us to remember, Bonhoeffer says, because what the prophet also sees is that right up to the instant the angel announces the fall of Babylon, Babylon “was still great, powerful, and bursting with strength—that Babylon was still standing there, invincible in the world.”

In other words, those who follow the Lamb are not promised an easy path. They’re given an eternal promise, the glad tidings of the gospel, by which they can stand strong in Babylon.

Except, notice—

The gospel the first angel proclaims is not a promise.

It’s a command.

During his one and only lecture tour in the United States, a lay woman in the audience asked the theologian Karl Barth:

“Professor Barth, will we see our loved ones in heaven?”

And Barth flashed her his trademark, irascible smile and said:

“Ja, not only your loved ones.”

Barth could so answer her because it is the word of God that it is the will of God that all shall be saved.

It is the word of God that it is the will of God that all shall be saved.

What the Seer sees, and more importantly what the Seer hears, in this passage is just such an instance of Barth’s assertion. The transition from “the book of the beasts” in chapter thirteen to this second vision of the Lamb marks another startling shift in mood and tone.

The Seer has just seen the unholy trinity— the Dragon and the Two Beasts— making war on the people of God and marking the whole world with the sign of the beast.

What Karl Barth calls “the lordless powers” win.

Or so it appeared.

But then the prophet shifts his gaze, away from the Beast and its Babylon and towards Mount Zion. And at the place where the temple altar once stood, the place long associated in Israel’s memory with divine deliverance from oppression, the Spirit shows the prophet the Lamb. Gathered around the Lamb, John sees, is the church militant— the church resistant; the confessing church. This is why John notes that the 144,000 have abstained sexual relations just as Israel’s soldiers did before battle.

At the place where Israel’s Lord once sat enthroned, the Seer first hears a voice.

The voice is triune.

The voice like many waters is Jesus.

The voice like loud thunder is the Father.

And the voice like harpists playing their harps is the Spirit.

John looks to Zion. John hears the voice of the triune God.

And the voice of the three person’d God is followed by a victory song, a song anticipated by the psalms, music of the Last Future.

The prophet shifts his gaze yet again.

Between heaven and earth, “another” angel is unveiled to the Seer, proclaiming “an eternal gospel to those who live on the earth—to every nation and tribe and language and people.”

The angel is preaching to those who’ve made peace with Babylon and happily ensnared themselves to the Beast and, thus, are in unwitting rebellion to the true God.

This angel, John reports, speaks with a preacher’s voice:

“Fear God and give him glory, for the hour of his judgement has come; and worship him who made heaven and earth, the sea and the springs of water.”

This is “the everlasting gospel:”

Fear God.

Give him glory.

Worship him.

All three— those are all commands not promises.

The eternal gospel is law.

Fear God. Give him glory. Worship him who made heaven and earth.

This is not a promise; this is a command.

Actually, it’s the first commandment:

“Choose me,” the Lord commands the Israelites, “And eschew all the rest. I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.”

The everlasting gospel is just the first mitzah to “have no other gods but God.”

The eternal gospel, like the first commandment, demands choice and faithfulness amid the panoply of possible gods.

In this vein, the greatest commandment is no different than the first.

When Jesus commands us to “love the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind…,” the word Lord in Jesus’s command is a proper name.

The Name, Yahweh.

The Lord’s angel preaches to those at ease in Babylon and in awe of the Beast because Israel’s God is intrinsically a jealous God.

Not to worship Yahweh only is not to worship him at all.

And because he alone is everlasting so is this gospel.

Around the same time Bonhoeffer preached on Revelation 14, another soldier in the church militant was standing strong in Babylon. Franz Jägerstätter was a Catholic peasant in a village not far from Hitler’s birthplace. When the Beast drafted Jägerstätter into the Third Reich, the father of four young girls refused to serve due to his Christian convictions.

Five months later the conscientious objector was put on trial by the Reich Military Court in Berlin. According to the trial records, Jägerstätter testified that it was impossible for him to be a Christian and at the same time a National Socialist.

God had given him the thought, he testified, that:

“There were matters in which one was obliged to fear God more than man.”

When his own defense lawyer pointed out to him that many Christians served the Nazi cause without conflict of conscience, Jägerstätter replied that our unfaithfulness does not mute what the true God has spoken to us.

While he awaited trial, Jägerstätter wrote an appeal to his fellow German Christians serving the cause of party, nationalism and tribalism, and xenophobia.

“Jump off the train,” he pleaded with them, “It’s headed to hell.”

Jägerstätter was martyred two years before Bonhoeffer.

Long after his execution, Jägerstätter’s fellow Austrians kept secret how he had stood strong in Babylon; so that, they could perpetuate the lie that they had only learned of the holocaust after the war. They did not want it known that they had fear another god but God. Not until 2007, when Pope Benedict celebrated Jägerstätter, did his story become widely known.

Hence the title of the film Terrence Malick made about him in 2019, A Hidden Life.

The film includes a scene where Jägerstätter, pondering the many friends who’ve insisted to him that “resistance is futile,” walks into his village church and discovers a painter at work, retouching the church’s frescoes.

Standing on scaffolding, the painter towers over Jägerstätter, and asks him to hand him up a piece of coal.

As he turns to his work, the painter reflects on his project:

“I paint the tombs of the prophets. I help people look up from their pews and dream. They look up and they imagine that if they lived in Christ’s time they wouldn’t have done what the others did. They would have murdered those whom they now adore.”

Then the painter points at frescoes on the ceiling and says to Jägerstätter:

“I paint all this suffering, but I do not suffer myself. I make a living of it. What we do is just create sympathy. We create admirers. We don’t create followers.”

A few moments later, the church bells begin to ring, and the painter takes up a small piece of gold foil:

“Christ’s life is a demand. We don’t want to be reminded of it.”

Later, outside the church, the painters confesses his guilt to Jägerstätter:

“I paint their comfortable Christ, with a halo over his head. How can I show what I haven’t lived? Someday I might have the courage to venture, not yet. Someday I’ll paint the true Christ.”

Fear God. Give him glory. Worship him who made heaven and earth.

Paint the true Christ.

Stand strong in Babylon.

The everlasting gospel is the first law, “Choose me and eschew all the rest.”

In his Remembrance Day sermon, Dietrich Bonhoeffer preached that the same gospel that is “mocked and attacked here and dragged through the muck, and yet loved in seclusion and secrecy and confessed by believers and martyrs of all ages, by countless hearts—the gospel remains eternally. It will abide in spite of it all.”

And then to his already frightened hearers, Bonhoeffer sharpened the Either/Or implicit in the eternal gospel.

Either the God who raised Jesus from the dead is the true God.

Or he is not.

Either the god who rescued Israel from Egypt is the true and living God.

Or all other claimants to deity are false.

As Robert Jenson jokes in his autobiography:

“It was not until college that it first occurred to me that my inherited religion claimed to be true— and therefore might be false.”

Neither the eternal gospel nor the first mitzah will broker any compromise.

As Bonhoeffer preached:

“And though there may be thousands of religions and spiritualities and philosophies and opinions and worldviews in the world, and though they may be the most beautiful of worldviews, and though they may well stir and move the human heart—they all collapse when confronted by death; they fall to pieces because they are not true.

Only the gospel remains. And before the end comes it will have been proclaimed to all nations, peoples, and languages over all the earth—though here it may seem that there are many paths, there only one will count, for all the people in the world: the gospel. And its language is so simple that anyone can understand it: “Fear God and give God glory, for the hour of his judgment has come; and worship him who made heaven and earth, the sea and the springs of water.”

That the prophet John is given to see not the far off future but our every day world with its different Babylons but all with the same Beast, the angel’s message is thus our mandate to proclaim.

Therefore, the question is necessary:

What is the gospel supposed to do?

As straightforward is the question, we seldom are clear about it; in fact, we regularly confuse the gospel with the gospel’s effects.

Again, what is the gospel supposed to do for its hearers?

Three passages are instructive.

In the Book of Acts, Paul and Barnabas perform a healing in the pagan city of Lystra; thereupon, the pagans confuse them for avatars of Zeus and Hermes. Paul rejects the honor and— offensively— informs them, “We are here to speak the gospel to you; so that, you may turn from such barren deities to the living God.”

In Ephesians, Paul invites the gentile believers to remember that prior to receiving the gospel they were “alienated from the commonwealth of Israel and strangers to the covenants of promise, having no hope and without God in the world.”

Likewise, Thessalonians calls the gospel nothing less than a summons “to turn from idols, to serve the living and true God.”

Simply, the gospel identifies who is the true God.

In a world with a smorgasbord of deities, the gospel invites you to turn from the false gods and introduces you to the true God.

This is precisely its good news.

And the effects of the gospel, “such things as forgiveness or liberation or empowerment or new creation or inclusion are merely what happen on the way” of this turning from the false gods of our cultures and to the true God of Israel.

So, for example, the worship of the false gods is sin, and therefore my conversion to the true God is forgiveness, and in its unsought and undeserved happening it is forgiveness by grace alone.”

As soon as you can answer the question, “What is the gospel supposed to do?” another question thrusts itself forward:

“Do we all worship the same God?”

It’s a genuine question, and the cultural and political and ideological pressure you may feel to answer hastily, “Yes!” (and the likelihood that a “No!” will cause your sphincters to tighten), is itself the kind of power that scripture calls a god.

For that matter, our own Babylon has many gods.

We willingly sacrifice our children to a deity called Inalienable Rights. Israel knew that same god and called him Moloch. I can name many people who have broken the fourth commandment, no longer speaking to their parents or their siblings out of loyalty to a political personality. Such loyalty is a barren deity. Martin Luther said that whatever you hang your heart on, there is your god. For many, that god is Family— Children— whose principle form of worship, travel sports, is as exhausting as the prophets of Baal trying to conjure fire.

I’ve been a pastor for over two decades and in that time I’ve known dozens upon dozens of people who have left their church because it did not align with the platform of their political party.

But I’ve known exactly zero people who have left their political party because it did not align with the convictions of their church.

That’s idolatry.

Back to the question, “Do all religions worship the same God?”

Robert Jenson writes:

“Of course, because there is only one true and living God, we may suppose that he receives all prayers and petitions however addressed or misaddressed. But, from this, it in no way follows that we all in our various religions worship the same God. Quite manifestly, we do not. And the Bible anyway is clear: there is the Lord, and there are the Baalim and Asherah, and to worship the Lord is to choose.”

To say that all religions are ultimately the same is to suggest that God is ultimately unknowable and unidentifiable, immune to time, and above history, but this is specifically what the God of Israel is not.

This exclusivity is exactly why the Jews have always suffered persecution.

You cannot worship the God who rescued Israel from Egypt and also the pantheon who tried to keep Israel in slavery.

Jesus is Lord means Caesar is not— but not only Caesar.

Not to worship the God who raised him from the dead alone is not to worship God at all.

As soon as you call Jesus Lord, you drastically reduce the ways you can rightly identify God.

As Stanley Hauerwas jokes, you can know we’re in Babylon with a pantheon all our own just to the extent Christians utter nonsense like, “I believe Jesus Christ is Lord, but that’s just my personal opinion.”

It’s a god that produces a sentence like “I believe Jesus Christ is Lord, but that’s just my personal opinion.”

At the end of his sermon, Dietrich Bonhoeffer pointed his frightened hearers to the beatitude in verse thirteen, “Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord…for their deeds will follow them.’”

“Our deeds do not prepare our path to Christ,” Bonhoeffer concluded his sermon, “faith does that—but our deeds follow, the deeds performed in God, in Christ, the deeds for which God prepared us from the beginning of the world…because they belong to us, they will be with us as the eternal gift of the true God.”

Fear God. Give him glory. Worship him who made heaven and earth.

The eternal gospel is law.

A command.

But so is, “Take and eat; this is my body broken for you.”

That too is a command— law.

And yet, nevertheless, it’s gospel.

It’s good news literally because the one who so commands is the true and only living God.

So come and receive him.

So that with him, you too might stand strong and paint a true Christ.