First Sunday of Advent: Genesis 21

A friend of mine, Rabbi Joseph Edelheit, recently forwarded me a poem written by the celebrated Jewish writer Maya Tevet Dayan. An Israeli citizen, Dayan composed the poem in the days following the October 7th massacre by Hamas. The poem was read in a synagogue in southern Israel during the Friday sabbath that followed the black Saturday of rage.

Dayan entitled her poem, “Trigger Warning:”

“Trigger warning : Sabbath

Trigger warning : Kibbutz

Trigger warning: Grass

Trigger warning: Party

Trigger warning: Baby

Trigger warning: Door

Trigger warning: Door handle

Trigger warning: Each time my daughter takes a shower in the evening, each I’m cold,

Each I’m hungry, each what would you like to eat, each omelette, each sweater,

Each I don’t want to wear socks, each “Mommy” (Trigger warning: Mommy), each time

Every hour when I wake up in the middle of the night (Trigger warning: Night, Night) each time the blanket rises and drops God make it rise and drop

Each time I whisper to myself in the dark

She’s here, she’s here,

Each time I whisper to her Mommy’s here, Mommy’s

Here.”

In the historic tradition, Advent begins not with luminous Chrismons nor with nostalgic anticipation of the birth of Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim. In the Church’s liturgical tradition, Advent begins in the dark and with desperate yearning for the return of Christ. Hence, every year Advent begins with John the Baptist wailing in the wilderness about the imminent winnowing fork of God’s wrath, “You brood of vipers!”Every year Advent begins by giving us Gospel passages with Jesus preaching apocalyptically, “Beware, keep alert…keep awake--for you do not know when the Master of the house will come.” And every year Advent begins with prophets like Isaiah forsaking any hope that we can improve our situation and pleading for God to rip the seam between heaven and earth and come down.

Every year Advent begins in the dark.

Every year Advent begins in the dark because Advent is the season not of the first coming but of the second coming. We are waiting in Advent not for the eve of his arrival to Mary and Joseph. We are waiting on the angel’s promise at the beginning of the Book of Acts, “This Jesus who has been taken up from you into heaven will return in the same way as you have seen him going into heaven.” This is why the Church in the Middles Ages spent the Sundays of Advent reflecting upon the four last things (Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell).

Advent is the season of the second coming.

Just so, Advent— as scripture itself does— beckons us to look for redemption from beyond another sphere entirely.

Or, as St. Gregory of Nyssa summarizes the takeaway of Advent:

“Any apparent progress forward in history is really, underneath it all, nothing more than the futile washing in and washing out of waves on a beach.”

Advent typically begins in the dark so as to force a frank and sober acknowledgment that sin is frighteningly real and that human progress is a deep deception. So understood, there is no better time on the liturgical calendar than Advent for the Church to sit with a poem like Maya Deven’s “Trigger Warning.”

Baby.

Door.

Door handle.

Nevertheless, an observant Jew like the poet Maya Deven might point out that such a stress on the Lord’s distance from the world’s darkness does not jibe with the only scriptures Jesus and the apostles knew.

The world can indeed be a bleak and broken place.

No one knows this closer to the bone than Jews.

The world can be awful and humanity evil but that does not mean the Lord is absent or uninvolved.

This is the unremitting confession of the Psalms:

“Where can I go from your spirit? Or where can I flee from your presence? If I ascend to heaven, you are there; if I make my bed in Sheol, you are there. If I say, ‘Surely the darkness shall cover me, and the light around me become night’, even the darkness is not dark to you…for darkness is as light to you.”

Advent begins in the dark.

But I wonder—

Should it?

Should Advent begin in the dark?

Should Advent accent absence?

Each time I whisper to myself in the dark

She’s here, she’s here,

Mommy’s here.

An Advent stress on Christ’s future return and the world’s present darkness can suggest a God who is otherwise removed from us.

To posit the incarnation as the invasion of God into enemy territory implies that the Lord was absent prior to Mary bearing God.

But such an aloof God is not the God of Israel. Indeed Mary’s assent gives a space for the God who all along has taken up space with his people Israel.

Incarnation has been God’s modus operandi all along.

As Daniel Boyarin, a Jewish scholar at the University of California, Berkley, writes:

“If there is one thing that Christians know about their religion, it is that it is not Judaism. If there is one thing that Jews know about their religion, it is that it is not Christianity. If there is one thing that both groups know about this double not, it is that Christians believe in the Trinity and the incarnation of Christ and that Jews don’t. If only things were this simple…there was a time when many Jews believed in something quite like the Father and the Son [Jews certainly believe in the Father and the Spirit] and even in something like the incarnation…Christian ideas are not alien to us; they are our own offspring and sometimes, perhaps, among the most ancient of all Israelite-Jewish ideas.”

Incarnation has been God’s modus operandi all along.

In fact, the claim of the gospel is still more audacious.

Not only is the God of Israel present to his people prior to the incarnation— the Spirit that overshadows Mary’s womb is the same Spirit who spoke by the prophets— the Lord Jesus himself is present to his people Israel more than a millennia before the Israelite named Mary gives birth to him.

This is the astonishing yet straightforward claim of the faith.

The events of the exodus occur thirteen hundred years before the nativity and the patriarchal narrative of Genesis recounts history that happened generations prior to God’s rescue of Israel from Egypt.

Thousands of years before she utters to the angel in Galilee, “Let it be with me according to thy word,” Mary’s boy comforts the mother of Ishmael in the wilderness of Beer-sheba.

This is what we have the audacity to assert every time we call God by his proper name: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

“Oh, how foolish you are,” the Risen Jesus gripes to the disciples on Easter, “and how slow of heart you are to believe…all of the Bible is about me.”

Exhibit A on the way to Emmaus very well could have been Genesis 21, in which the Lord Jesus consoles Hagar, Abraham’s Egyptian slave, “What troubles you, Hagar? Do not be afraid…for I will make a great nation of him.”

As the ancient church father Tertullian puts it, in God there are three dramatis personae Dei, three persons of the divine drama. What scripture does is tell the drama of God with his people, showing three personae of the drama, each of which is other than the other two and yet is the same God as the other two. From the very beginning, the Father and the Spirit are straightforwardly two dramatis personae in the Old Testament, but what of the Trinity’s third person? “The Son’s presentation in the Old Testament,” Robert Jenson writes, “is even more clearly a matter of a plot-structure displayed both by the Old Testament’s total narrative, and by many of its individual incidents.”

For example, look again to the passage in Genesis.

Ishmael is the Plan B product of Abraham and Sarah having despaired of God’s promise. With Isaac weaned, Sarah feels little enthusiasm for Abraham’s and Hagar’s son sharing space with her own boy. At his wife’s insistence, Abraham casts off Hagar and Ishmael, exiling them into the wilderness where mother and child fall into weeping.

Take note how the passage displays the reality of God:

“The angel of God” speaks to Hagar “from heaven.”

The angel of the Lord at first refers to God in the third person, “God has heard the voice of the boy.”

Next— pay attention— without any break in the angel’s discourse, the angel shifts into the first person, “I will make a great nation of him.”

The angel of the Lord is thus one who simultaneously speaks of God in the third person and in the first person. The angel of the Lord is both one who is other than God and also one who is identical with God and is God’s speech-act. Or, as John puts it plainly in his own nativity of sorts, “The word is with God and just so is God.”

What the Gospel of John calls the Logos, the Old Testament calls the Angel of the Lord, both another than God and by virtue of the character of his otherness also God.

Again, don’t take my word for it.

As the Jewish scholar Daniel Boyarin writes:

“The Angel of the Lord is precisely the point of a tension or ambiguity about monotheism at the heart of Israel’s religion. Throughout the Hebrew Bible there is confusion between YHVH himself, as it were, and his Mal’akh, the single, unnamed angel of the Lord, precisely in theophanies…No clear-cut distinction between YHVH this special Mal’akh is intended; they are two aspects of one divinity.”

If you follow—

That’s a Jew giving you, a Christian, permission to believe.

Believe:

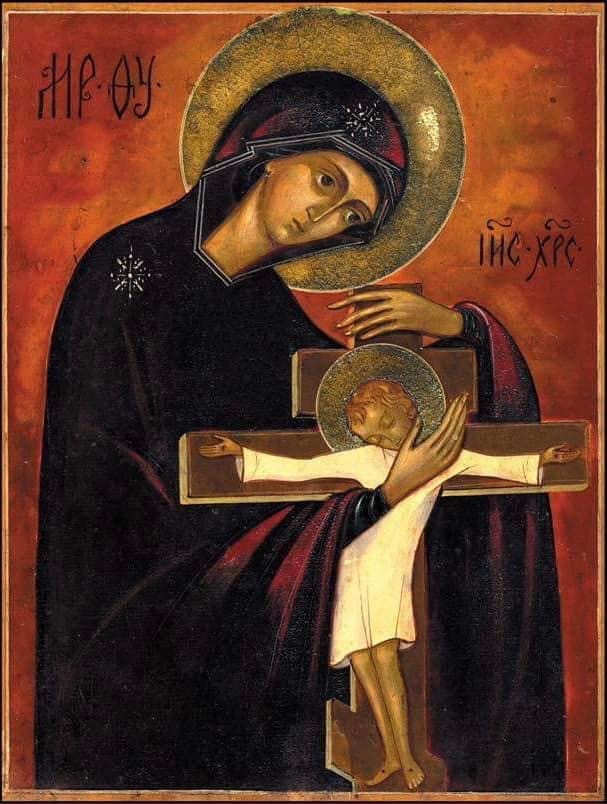

Jesus is the one who comforts Hagar in the wilderness.

Jesus is the one who meets the mother in her darkness, her fright and despair for her child, and says, “I’m here.”

How can this be so? The Christian answer is Easter. It’s the Risen Jesus, come from the Last Future— back in time, who consoles Hagar and cares for her son. You see— as a Christian, you have permission to believe astonishing things!

Maya Dayan, the Jewish poet, wears a bracelet she received at the music festival just prior to the October massacre at the hands of Hamas. It reads, “Radical love.” And yet, she writes, “I keep a long kitchen knife by my pillow. Fear has no limits and no sense. My land is bleeding. The same knife with which I cut salad for my daughters for supper is the one that lies by my head at night. I don't know how to tell my girls that brutality isn’t necessarily over even after a massacre ends.”

The darkness is real.

Your darkness is real— whatever black cloud enshrouds you.

Nevertheless!

Neither Advent nor any other season in your life can begin in the dark.

It just cannot— darkness can never be the starting point for any of us.

Because wherever you are, the Friend of Sinners is already there.

And maybe you can’t hear him. Perhaps you can’t see him in the dark. But, like a mother over her child, Jesus is whispering to you, “I’m here. I’m here. I’m here.”

Share this post