Colossians 2.1-15

Almost eight years ago, not long after the inauguration, as thousands of outraged people gathered at airports across the country to protest the new administration’s so-called Muslim ban, I observed online Christian influencers, one after the other, post exhortations on social media such as, “If your pastor isn’t preaching on immigration this Sunday, then you need to find a new church. If your church isn’t speaking out against the Muslim ban this Sunday, you need to find a new church. If your preaching isn’t preaching with the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other hand, then you need to find a new church.”

The goading went viral.

The exhortations accused me every time I opened an app.

Nevertheless, I did not mention the matter that Sunday. I wanted to do so—I had and I have my own convictions. But I did not bring up politics in the pulpit because I simply did not know how to connect the contemporary issue to the day’s biblical passage, the Gospel of John, chapter eight— the woman caught in adultery. I did not see a clear connection between the headlines and the scripture, and as a preacher I had to trust that, even with the world swirling in turmoil and chaos, there was something more important going on in God’s word.

So I stuck to the text.

You know the story, how Jesus practically begs the Pharisees to stone him when he says to the sinful woman, “Neither do I condemn you.”

“I just do what I see the Father doing,” Jesus says.

After the service, I was standing in the narthex when a man a bit older than me took my hand to shake it but then he didn’t let go. He wore a blue blazer and faded jeans and the red stood out on his otherwise fair cheeks. His eyes were wet and righteously angry.

He whispered but his rage was deafening.

“I’m the husband of a woman caught in adultery. I’m the husband of the woman in that story. Where’s my sermon? Do you have any idea how angry your sermon makes me? After everything I put up with— the humiliation, the shame, the learning that what I thought was my life was actually a facade, a fantasy! And then I come here looking for a little hope and peace and you’ve got the nerve (he didn’t say nerve) to tell me that God is gracious?! To her?!”

He was still holding my hand in a clammy, irate grip.

He pulled me towards him, “What do you have to say about that?”

I stammered, “I guess I should’ve preached on the Muslim ban.”

“What?” he replied, looking confused and enraged.

“I meant,” I explained, “I’m grateful that I stuck to the text today. It sounds like Jesus Christ did some work on you this morning.”

He dropped my hand, suddenly, like it was a poopy shoe.

“That’s all you have to say to me?!”

He was no longer whispering.

“Well?” he challenged, putting his hands on his hips.

I nodded, took a deep breath, and looked him square in the face.

“I’ve heard your confession,” I started to say.

“Confession?! I’ve not confessed anything.”

“Sure you have,” I said, “You just been confessing to me all about your anger and your hate and your un-forgiveness for your wife.”

In an instant, his face went from red to white, like he was the one who had been caught in the act.

“Where was I— I’ve heard your confession, and in the name of Christ Jesus our Lord and by his authority alone, I absolve you of all your sins.”

His jaw fell open.

“Oh my God,” he stuttered, “I had no idea that was exactly what I needed to hear.”

And then he started to weep. His knees buckled. And rather than fall over, he toppled into an embrace of me. It’s hard, I suppose, for the dead to walk after they’ve just been raised to new life.

“And you, being dead through your trespasses…you he made alive together with him, having forgiven us all our sins, having blotted out the bond written in ordinances that was against us, which was contrary to us. And he has taken it out of the way, nailing it to the cross.”

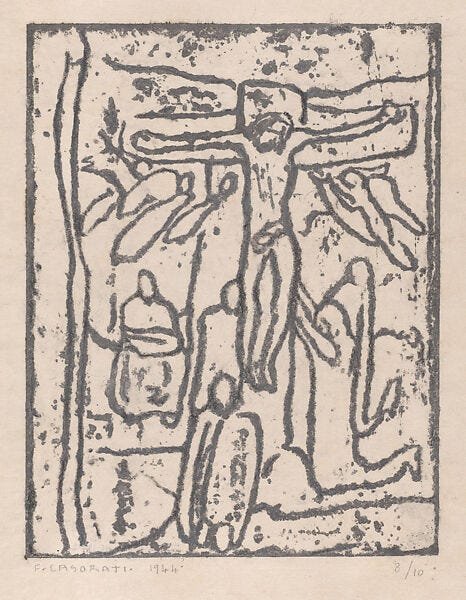

In 1968, during the recovery efforts after the Six-Day War, Israeli construction workers discovered the remains of a crucified man from the time of Jesus at Giv' at ha-Mivtar, in northeast Jerusalem. The victim's ankles appear to have been penetrated from the side by nails. Between the head of the nail and the right anklebone are remnants of a piece of wood that may have been used to extend the head of the nail. The feet seem to have been hacked off after the body's removal from the cross. The two shin bones and left calf bone are broken. Finally, the victim's underarms appear to have been bound to the cross since there is no trace of damage to hands or wrists.

These remains are the sole evidence in all of antiquity of a crucified man.

After their slow, languishing death, Rome left the naked bodies of the crucified upon their crosses for carrion to pick them apart into oblivion. The entire point of crucifixion was not the pain it induced but the shame and degradation it inflicted. The manner of death was meant to render its victim a non-person, to blot them out of history permanently. Rome was so successful that crucifixion's only remains remain that body unearthed by Israeli laborers.

How odd of God then that in Jesus Christ, the Lord uses the same means to blot out the writ against us.

Notice how from verse thirteen to verse fourteen Paul shifts from the second person plural to the first person plural, from you (i.e., the Colossians) to us (i.e., everybody). In other words, every distinction between you and me collapses at the foot of the cross:

“When you were dead in your sins…God made you alive with Christ— He forgave us all our sins. God has blotted out the writ that was against us, He has taken it out of the way for us, nailed it to His cross.”

The Greek word translated variously as writ or handwriting of ordinances is cheirographon and it means, simply, a note of debt. It’s a rare word in the New Testament, but you know it from the prayer Jesus commands us always to pray, “Forgive us our cheirographon as we forgive the debts of others.”

A cheirographon is an IOU.

Thus, “God has blotted out the IOU that stood against us, he has removed it, nailing it to his cross.”

Now, importantly, because the writ against us is an IOU, the writ is not the law. An IOU is signed by the debtor not by the one to whom the debt is owed, and the law bears not our signature but the Lord’s. Therefore, we stand accused not by the Jewish law but by a more foundational, universal IOU that makes intelligible Paul’s transition from you to us.

The debt of Adam.

The sin of Adam.

Just so, what Paul says here to the Colossians is no different than what Paul proclaims to the church at Rome:

“As one man’s trespass led to condemnation for all, so one man’s act of righteousness leads to justification and life for all. For as by the one man's disobedience the many were made sinners, so by the one man's obedience the many are made righteous.”

Contrary to much of the deconstruction of the gospel in progressive circles, Jesus is not the tragic, passive victim of Empire and Religion colluding against him.

According to Colossians, what is nailed to the cross is the IOU owed by us all. As Martin Luther says, Christ bears our actual sins in his body on the tree.

What is nailed to the cross is the writ against us.

And it’s the Father and the Son with their Spirit— not Pontius Pilate— it’s God who nails it there.

Christ just is the cheirographon.

In Pilate’s attempt to blot out Mary’s boy by means of a cross, the triune God in fact blots out all our sins; such that, I can hand over a promise only God can promise.

You are forgiven.

When he was a novice preacher at a parish in Safenwil, Switzerland, Karl Barth, the future theologian, subjected his congregation to sermons on the sinking of the Titantic and, later, on the issue above the fold of every newspaper, the Great War. Looking back on and confessing his early homiletical mishaps, Barth recalled a woman from his church who grabbed him one Sunday by the lapels and begged him, “Please preach on something else other than this dreadful war.”

Not yet understanding how unfaithful he had been at his task, the pastor asked his parishioner what she thought he should preach.

She responded at first by staring at him, astonished he should not appreciate the urgency of the summons laid upon him.

“What shall you preach? The gospel of course— the promise of grace, the word of the cross, the forgiveness of sins. There is no dearth of bad news in the world. You cannot afford to neglect the good news.”

“He forgave us all our sins, blotting out the handwriting of ordinances that was against us, taking it out of the way and nailing it to his cross.”

The reason Paul writes this epistle to the Colossians is to caution them against falling captive to “the elemental spirits.” The elemental spirits lie behind what Paul calls “hollow and deceptive philosophy.” As N.T. Wright comments on this passage, the elemental spirits refer specifically to “the tutelary gods who preside over pagan nations and ethnic tribes.” That is, the elemental spirits represent the melding of God with Country, Religion with Race and Identity— a kind of first century ethnocentric Christian nationalism. Evidently it was as dangerous then as it is now, for it is the occasion that Paul writes this letter to the church.

If your apostle isn’t preaching about Christian nationalism this Sunday, then you need to find yourself another church.

“Surely, you have a word about this for us,” the apprentice Epaphras appeals to his mentor.

And so Paul prays and writes and delivers to them a message.

But notice—

The problem in the world that demands a word from the Lord, the issue tearing at the seam of the church’s unity, the trouble tempting believers away from their brothers and sisters in Christ, Paul speaks to it in a single sentence only.

Verse 8:

“See to it that no one takes you captive by philosophy and hollow deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the world, and not according to Christ.”

The lure of the elemental spirits is the very problem that prompts Paul to write this letter in the first place, but then Paul gives it no more of his attention than a solitary verse before he resumes proclaiming the promise.

To the issue in the world about which the church must say a word, Paul devotes one sentence.

To the gospel without which the church has no word at all for the world, Paul piles up an overwhelming number of verbs at the end of this passage— eight verbs in three verses, with God the subject of them all.

Make alive.

Forgive.

Blot out.

Take away.

Nail.

Disarm.

Put to shame.

Triumph.

As if to say—

About a great many things, the church can say any number of things. But one thing the church must always say: “He forgave us all our sins, blotting out the handwriting that was against us, taking it out of the way and nailing it to his cross.”

Of all the things we can say, that’s the only word that can kill and make alive.

Nearly four years ago, Officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd in cold blood in Minneapolis. For nine minutes, Floyd pleaded, “I can’t breath.” Until finally he couldn’t and his breath became air. With protests flooding the streets and cities starting to burn, the online influences threw down the gauntlet once again, “If your pastor isn’t preaching about George Floyd this Sunday, then you need to find another church. If your church isn’t speaking out against racism this Sunday, you need to find a new church.” Some of you took me to task for not preaching about it the following Sunday. And maybe you were correct to do so.

I had prerecorded the sermon and I was out of town, visiting my niece, but if I’d wanted to do so I could have scrapped the sermon and responded to the moment. At that point in the pandemic, we were good at the technology. Instead I stuck to the text. Even with the world afire with righteous anger, I took it as an item of faith that something more important would be going on with God’s word.

The passage was a different epistle, Paul’s non sequitur in his letter to the Corinthians, “One has died for all; therefore, all have died.” It’s a non sequitur. It doesn’t logically follow that because one man died, all have died. The conclusion does not naturally follow the premise because it’s unnatural. It is revelation.

The one man who died for all is God.

Therefore, all have died to sin.

“You’re home free,” I preached, “You’re safe in Christ and him crucified.”

Later that afternoon, I received a phone call as I drove home from Cleveland. “Are you the pastor— the one who preached that sermon I stumbled across on Facebook?”

“I am,” I mumbled, wondering what this stranger was about to say with my mother sitting next to me in the passenger seat.

“I need to meet with you, in-person, right away,” she said.

I offered her the following morning.

“I think you might just be the person to blame me.”

“Blame you?” I started to say, but she had already hung up.

The next morning I invited her to sit on the sofa in my office. She ripped off her mask and collapsed on the couch like a suitcase thrown onto a motel bed.

“Everyone, for years, has told me that it’s not my fault— my therapist, my doctor, my son’s doctor, my friends.”

“What’s not your fault?”

“My son has special needs,” she answered.

And quickly I interrupted her, “I think I’m with your therapist on this one.”

She held up her hand to silence me.

“Listen!”

She said it so loudly I had no choice but to obey.

“When I was pregnant, I drank. Not all the time. Not every day. But not once. Or twice either.”

She looked at me to see if I understood.

“I did that,” she said with all the matter-of-factness she could muster, “And everyone wants to tell me that it’s not my fault.”

I nodded.

“I saw your sermon and I thought you might be someone who had something different to say to me.”

“It’s my fault,” she said.

“Yes,” I said, “Or, quite possibly.”

She closed her eyes like she’d been in the desert and had finally found water.

When she opened her eyes, she was surprised to see me standing in front of her. I made the sign of the cross over her and I said to her, “For this sin and for all your other ones, I absolve you in the name of Jesus Christ.”

She dried her eyes and wiped her nose with her face-mask. She stood up, kissed me on the cheek, and left down the hallway.

She emailed me every day for a year:

“You set me free to love my son. You set my son free from being the object of my shame instead of the object of my love. You delivered us into a whole new life.”

“Not me,” I replied the first time, “I didn’t even remember to zip my fly this morning.”

On Friday afternoon, I got a phone call from a reporter looking for a comment about our denomination’s global gathering and the conclusion to its long fought feud over the full inclusion of LGBTQ Christians. I corrected some of the errors in his legislative takeaways, and I supplied him with some biographical detail about myself. And then he asked me a question. “I just want to get a quote,” he said, “In light of the changes in your church, what are you going to preach this Sunday?”

As soon as he asked me the question, I thought of that mother, in my office, on my couch, her eyes closed liked a desert wayfarer.

“What am I going to preach this Sunday? The same thing I preached last Sunday. The gospel.”

He laughed like I was joking.

“Seriously?” he pressed, “Do you not support the fact that your church is now fully inclusive?”

“Of course I support it,” I said, “I celebrate it— I’ve had more skin in the fight than most people know, going back almost twenty-five years.”

“So why don’t you plan on preaching about it this Sunday?”

“Here’s the thing,” I said to him, “I’m a preacher. I’m even a Christian. We’re in the resurrection business. There’s nothing wrong with a word like inclusion or welcome. Those are good words. The problem is that neither of those words have ever demonstrated the ability to raise the dead to new life. We’ve only got one word that can kill to make alive.”

“I don’t know that I can use that quote in my story.”

Look, I don’t know who called you on Friday or how you spent your week. But here’s what I do know. Not one of you— gay or straight, black or white or brown, old or young, married or single, rich or poor, homeless or housed, Republican or Democrat, Pro-Israel or Pro-Palestine, yay or nay on Taylor Swift’s latest album— not one of us made it through this week having practiced the perfect righteousness that the holy and triune God demands.

Somewhere between Monday morning and last night you fell short of the total obedience to the law that the Lord commands.

Which means, you came here today in the very same condition in which you showed up last Sunday, dead— dead in your trespasses. Therefore, yet again, unless you want to stay dead, you need to receive and believe a particular promise, the only word that can get death behind you.

Today it sounds like this:

“And you, being dead through your trespasses…you he made alive, having forgiven us all our sins, having blotted out the IOU that was against us. He has taken it away, nailing it to the cross.”

Of all the things we can say, this is the only word we must say.

Trust and believe.

I know!

Some of you accuse me only having one arrow in my quiver, grace.

Blame Jesus!

Every time he shows up on Sunday, he says the same thing too.

Every Sunday he gives you himself and says the same two words, “For you.”

Share this post