Genesis 32.1-32

All this time spent with Jacob, and I’ve neglected to make the fact explicit.

I like Jacob.

I like Jacob even though its not clear from the biblical witness I’m supposed to like Jacob. In a culture that prizes the eldest son, Jacob isn’t. In a religion whose exemplar, Abram, leaves everything behind to follow by faith when God calls, Jacob doesn’t. I like Jacob, but in a tradition where names mean everything, convey everything, foreshadow everything, it’s not clear from the name “Jacob” that we’re meant to root for this character.

When he was yet unborn, Jacob, who wrestles God in the dark along the riverbank, for nine months wrestled his twin brother in the dark waters of his mother’s womb. And when she gives birth to them, Esau first, the youngest comes out clutching at the leg of the eldest.

As if to say, “Me first.”

So Rebekah names him “Jacob.”

Which in 2023 is a little like naming your kid “Elon.”

In Hebrew “Jacob” means heel-grabber, hustler, over-reacher, supplanter, scoundrel, trickster, liar, cheat.

In a religion where names signify and portend everything, it’s not clear that I’m so meant but, nevertheless, I like Jacob.

It’s true scripture gives us plenty of reasons to dislike Jacob. More than twenty years before they meet face-to-face on the banks of the Jabbok River, Jacob took advantage of his brother. One afternoon Esau had returned from the fields, dizzy and in a cold sweat from hunger. Jacob pulled some fresh bread from the oven and ladled some lentil soup from the stove. When Esau asked for it, Jacob demanded his elder brother’s birthright in return.

As Jacob knew it would, Esau’s birthright seemed an intangible thing compared to hunger. Esau accepted the terms of his brother’s extortion. And even if Esau knew not what he’d just done, Jacob certainly did.

But I still like Jacob.

It’s true that his birthright isn’t the only thing Jacob poaches from his brother. It’s true that when their father, Isaac, was weighed down by age and his eyes were cobwebbed by years, when Isaac was dying and wanted to bless his eldest son- a blessing to be the most powerful of all, a blessing that couldn’t be taken back - the old man lay in his goat-skin tent waiting for his eldest son to appear.

After a while he heard someone enter and say, “My father.”

And the old man, his eyes darkened by blindness, asked, “Who are you my son?”

Heeding his mother’s orders, the boy boldly lied and said that he was Esau.

And when the old man reached forward to the touch the face he could not see, the boy lied a second time. And when the boy leaned over to kiss the old man and the old man sniffed the scent of Esau’s clothes, just as Jacob knew he would, Isaac blessed him. Jacob lied to his father to steal from his brother the birthright that he coveted. If you’re counting at home, that’s three of the ten commandments, broken in one fail swoop.

Still, I’ve got my own reasons. I like Jacob.

It’s true that soon after Esau’s rage made Jacob a runaway, God spoke to him in a dream— gave him a vision of a ladder traveled by angels— it’s true that when Jacob awoke from the dream and marked the spot with an altar stone and prayed to God, Jacob didn’t pray for forgiveness. He didn’t confess his sin. He didn’t express any remorse or give any hint of a troubled conscience. Instead Jacob prayed with fingers crossed and one eye opened, a prayer that was really more of a deal, “If you stand by me God, if you protect me on this journey, God, if you keep me in food and clothing, and bring me back in one piece to my house and land, then you will be my God.”

Yet, it’s hard for me not to like Jacob.

I know it’s true that when he had nowhere else to go, his mother’s brother, Laban, took Jacob in and gave him food and shelter and work and, eventually, wives and a family. I know it’s true that after over fourteen years of Laban’s hospitality Jacob became a rich man— but not rich enough to satisfy Jacob who returned Laban’s good deeds by cheating his father-in-law out his wealth. I know it’s true that God, in his compassion, gave children to Leah because Leah’s husband Jacob gave her neither a thought nor a care.

If you’re still counting at home, that’s another couple of commandments broken (which still gives him a winning percentage better than the Washington Nationals are likely to have this season.)

Jacob’s a liar, a cheat, and a thief.

Jacob’s got a wandering eye and a fickle heart.

Jacob’s got shallow scruples and fleet feet.

Jacob’s always ready to run away from his problems.

Jacob’s not a Bible hero.

He’s a heel.

Still, I can’t help it. I like Jacob.

You might not.

You might not like Jacob.

You might not be like Jacob.

Maybe you’re batting perfect when it comes to the commandments.

Congrats. Kudos.

Maybe you’ve never lied to your mother or your father or your husband or your wife. Maybe you’ve never watched idly by as a sibling or a friend or a neighbor wanders out of your life and in to trouble and then beyond your reach. Maybe you’ve never betrayed someone you should’ve honored and obeyed. Maybe you’ve never returned a good deed with a petty one, or turned to God only when you needed him. Maybe. Maybe your family’s never suffered such bad blood that it threatens to hemorrhage or maybe you’ve never let the wounds of a broken relationship fester through years upon years. Maybe you’ve never withheld forgiveness because clenching that forgiveness in your fist was the only control you possessed.

At every point, from his mother’s womb to Jabbok’s river, Jacob has worried about Jacob. Jacob has only ever cared about Jacob. Jacob has looked after no one else but Jacob.

Maybe you’re not like that. Maybe you’ve never been like that. Good for you. Gold star to you. Go ahead and turn your brown nose up at Jacob.

Just because I like him doesn’t mean you must.

Not everyone can relate to Jacob.

Not everybody can identify with someone who suspects his sins are eventually going to sneak up on him from the shadows of his past.

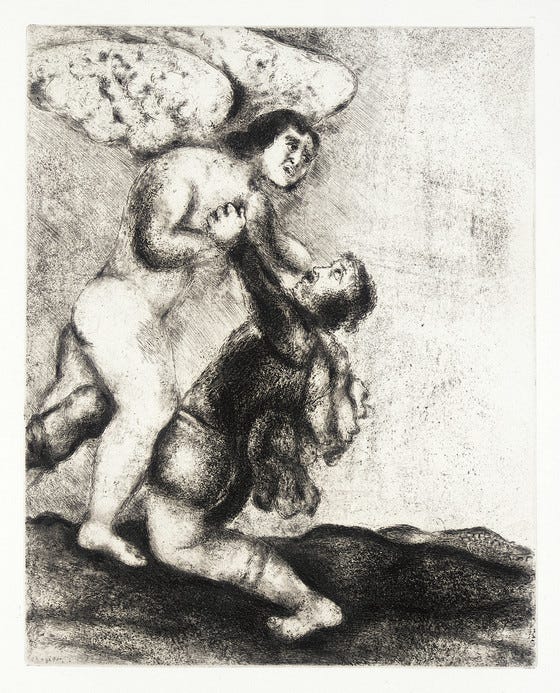

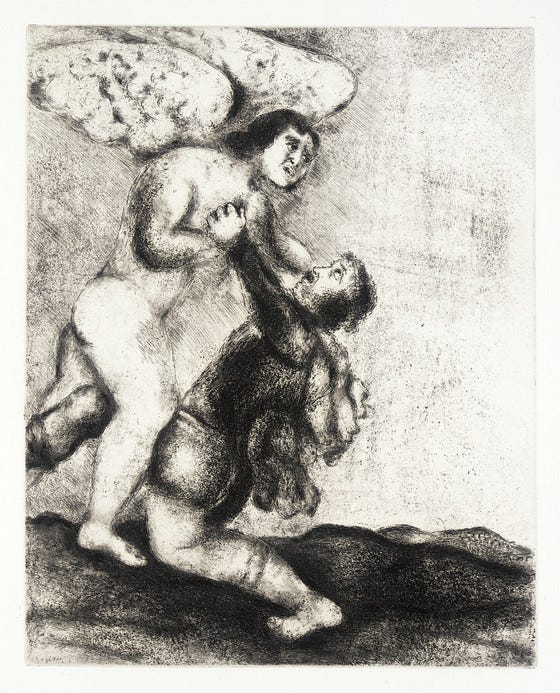

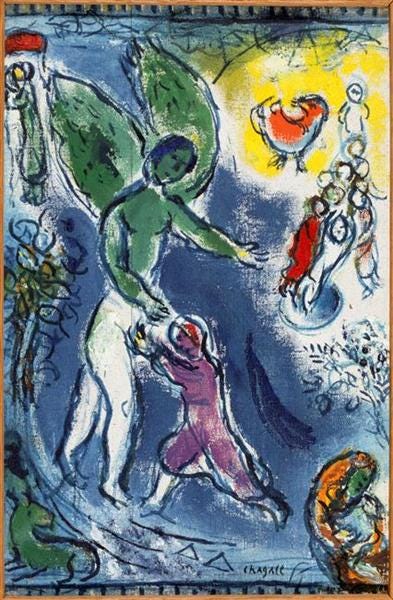

Check the text— Jacob sends his wife and his kids and his possessions packing before a stranger jumps him in the dark and fights dirty until dawn. Jacob ships them off across the Jabbok and then he just waits in the dark for a shadowy struggle he apparently anticipated but had no actual reason to expect.

In other words, the stranger in the shadows doesn’t surprise Jacob because Jacob was expecting that, sooner or later, the other shoe would drop, the bottom would fall out, and his ill-gotten gain would get him.

Maybe you can’t identify with someone like Jacob.

Maybe your rap sheet is clean.

Maybe your conscience is clear.

Maybe your you-know-what really doesn’t stink and so whenever the you-know-what hits the fan it never occurs to you that you had it coming.

Maybe you’ve never clutched the covers at night convinced, “This is happening to me for a reason. God’s doing this to me because of what I’ve done (or left undone).” Maybe you’ve never wondered that this sickness or struggle is because of that sin. Maybe you’ve never harbored the suspicion that the darkness that’s enveloped you is what you deserve.

Lucky you if you can’t relate to Jacob.

Lucky you.

Lord knows I can.

I can.

But that’s not why I like Jacob.

I remember years ago I received a sympathy card with Jesus on the cover.

The card depicts Jesus from the rear. His cloak is piled around his ankles falling on the tile of a bathroom floor. Someone— maybe his mother, Mary— is holding his long, dark hair back away from his face.

He’s squatting.

You know it’s Jesus even from the rear because you can see his wounded feet tucked under his knees. And his pierced hands are gripping the sides of a toilet bowl with the lid up.

He’s about to hurl.

The speech balloon above Jesus’s head reads:

“Don’t listen to my friends. I never said my Father won’t give you more than you can handle.”

That’s why I like Jacob.

I like Jacob because after several years of living with incurable cancer, after eight rounds of stage-serious chemo, after more rounds of maintenance chemo than I can count, after one surgery and thousands of needle pricks and transfusions and panic attacks and thinking about that hour glass from Days of Our Lives, Jacob might be the one person who would never dream of sending someone like me a card that said, “God never gives you more than you can handle.”

Someone like Jacob would never cross-stitch a cliche like that onto oven mitts and leave them with a casserole at my front door.

I like Jacob because Jacob, whom God leaves lame and limping and bruised below the belt, knows that the good news is NOT “God never gives you more than you can handle.”

Jacob has the scars to prove it.

The good news— the only good news— is that God meets us in the very midst of that which we cannot handle.

I spent last Tuesday at the infusion center receiving my latest monthly maintenance chemo to keep the cancer at bay. I’ve been to the infusion center so often my iPhone recognizes the “Cancer Specialists” WIFI network.

Before my chemo infusion, my oncologist felt me up for lumps and red flags. Like he’d done at all my previous visits, the doctor flipped over a baby blue hued box of latex gloves and, with a sharpie, sketched out the standard deviation of years until relapse for my particular flavor of incurable cancer.

Cancer didn’t feel very funny staring at the bell curve of the time I’ve likely got left. Until. When the doctor was done feeling me up, my nurse came to poke around for a vein big enough to handle the chemo. It sounds pathetic but you get to the point where you’re just tired of being sick and stuck all the time with needles.

One of the two TV’s in the lab every commercial break— I’m not exaggerating— featured an advertisement from Lexington Plastic Surgeons, who, according to the voiceover pitchman, have more offices around the country than Skynet.

“Do you think I’d look good if I got a Brazilian Butt Lift?” I asked my nurse as she clamped the needle down into my arm.

She raised her eyebrow at me.

“Um…maybe?” she replied, “You’re not really my type, butt lift or no butt lift.”

The other TV in the lab was playing Rachel Ray’s cooking show.

Every commercial break of Rachel’s show featured a spot selling Rachel Ray’s own line of boutique dog food, which if you’re counting at home is reason #93 to hate Rachel Ray.

“Do you think it strange that in between recipes for people food Rachel Ray is also selling dog food? I mean, are those transferable skills?” I asked my nurse.

She laughed as she hung my bag of pre-meds.

She had short buzzed hair that she’d dyed turquoise that matched the gem stud in her nostril and complemented the purple cat-eye glasses on her nose.

Looking at the tattoo on my arm, she told me that her girlfriend was a tattoo artist.

“We’re thinking of getting married, my girlfriend and me,” she said, “You’re a priest, right? You probably think we’re sinners?”

She was asking, I noticed, not accusing.

“If you’re going to ask me these sorts of questions, I think you should return my copay.”

But she just sat on the wheeled stool next to me, waiting on me.

“Sinners? Yes.” I said.

And then added: “But no more than me.”

She looked confused, like what I’d said wasn’t as bad as she’d feared and not as good as she’d hoped.

“Look,” I said, “Christians have a simple formula:

People are sinners. Christians are people. Christians are sinners.

“So yeah, no more than me.”

She nodded and flicked the tube to start the drip.

Another commercial from Skynet came on the television, this one for breast augmentation and eyebrow lifts and wrinkle removing along with a lie about defying time and aging.

“It’s kind of a waste of their ad budget to have their commercials played in here, don’t you think?”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, it’s kind of obvious and unavoidable here that nobody is getting out life alive but that’s exactly what they’re promising.”

She handed me a little plastic cup of pills (meds to minimize the tremors the chemo causes) and she said:

“Can I ask you, since you brought it up, if you died— or, when you die— do you know where you’ll go?”

“What are you?” I asked, “Some sort of undercover lesbian evangelist?”

She smiled just a little.

“No, I’ve just never been that religious and I don’t know how you know, you know, that you’ll go to heaven or be with God or whatever.”

I nodded a yes.

“You’re really certain?” she asked me.

She was studying me, the way she did at the end of infusions to make sure I was okay to drive home.

She was studying me so I said it, “Yes.”

“How can you be so sure? How can you have that much faith?”

I shrugged my shoulders.

“I am certain,” I said, “but I don’t know that it’s any great faith. I’m sure because, well, because God told me so last Sunday.”

This is my body broken for you.

She narrowed her gaze, trying to determine if I was punking her. She must’ve decided I was playing it straight because, as she smoothed out my crinkled chemo tube and she asked me, “Do you ever wonder where God is…considering…” and she looked around the room and back to me and the chemotherapy bag.

Now it was my turn to stare and study her.

“You see a lot of people lose their faith in a place like this,” she said, “I guess it can be hard to believe there’s a God somewhere in the universe when there’s places like this in it too.”

I shook my head.

Your problem,” I said, “is in thinking that God is somewhere other than right here in a place like this.”

I don’t just like Jacob; I think we need him.

Martin Luther said that, from Adam onwards, you and I are addicted to what he called the “glory story.”

That is, we’re hard-wired by sin to imagine that God is far off in heaven, up in glory, doling out rewards for every faithful step we take up towards him and doling out chastisements for our every slip-up along the way.

It’s the glory story that produces cliches like, “God never gives you more than you can handle” and “Everything happens for a reason.”

It’s the glory story that provokes questions like, “Where is God in the midst of my suffering?”

The glory story prompts those kinds of questions and cliches because it gets the direction of the gospel story backwards. The gospel story, the story of the cross, is not the story of our journey up to God but God’s journey down to us. The story of the cross is a story of God’s condescension not our ascension. And the story of the cross isn’t a story that starts with Jesus. Rather the God who comes to us in the crucified Christ is the God who has always condescended. Indeed, that’s why the first Christians believed it was the Lord Jesus Jacob wrestles here in the dark of the night. This angel in the darkness is the Second Adam who has the authority to (re)name God’s creatures.

And so I don’t just like Jacob; I think we need him.

We need Jacob to inoculate us against the glory story and all the unhelpful questions and cliches it begets.

We need Jacob to remember that:

If we are to find strength from God it starts with searching for him in our weakness.

If we hope to find wholeness from God it begins by seeking him out in our wounded-ness.

If we dream of finding healing from God we first must look for God not up in glory but down in the shadows of our sufferings.

Without Jacob, when we cry out to God for help and healing we are liable to point our mouths in the wrong direction. Up into glory rather than down in to the darkness and out into the shadows that surround us.

So I don’t just like Jacob; I think we need him.

Because it’s not just that the power of God is revealed in the weakness of Jesus Christ, it’s that the grace God gives to us in Jesus Christ— the healing grace God gives to us in Jesus Christ— can only be received in a weakness like Jacob’s.

Only in our weakness and wounded-ness do we realize our true helplessness and only in helplessness can we discover the healing power of his blessing— that’s not just the Jacob story that’s the gospel story.

That’s the one way love of God called grace.

That’s what we mean when we say that you are saved in Christ alone through trust alone; we mean that you alone— by your lonesome— do not have the strength to save yourself. You are as helpless as Jacob, hobbled over with his hip out of joint. That’s why the bread is broken and why you come to the table with the open, empty hands of a beggar.

It’s only when you realize you have nothing to offer that you’re ready to receive what God has to give.

As she pulled the needle from my arm, I said to her, “Your problem is in thinking that God is somewhere other than right here, in a place like this. You’re making a mistake that goes all the way back to the beginning of the Bible. God isn’t up somewhere in glory. The true God isn’t anywhere but here in the shadows and the darkness and the suffering. The true God leaves behind wounds because he meets us in our struggles.”

But I could tell from the squint behind her purple glasses that she didn’t follow me so I said to her:

“Look, since you’re the lesbian evangelist nurse, this might come in handy the next time you see someone on the edge of unfaith.

Tell them, “God didn’t give you cancer, but if God is to be found anywhere it’s in your experience of cancer.”

Tell them, “God makes his office at the end of your rope.””

“Which means,” I added, “the question for faith is not “Where is God in the midst of my struggle?” As though, God is absent. The question for faith is “What is God up to in the midst of my struggle?””

What is God up to?

To all of you who are just hanging on, to any of you who are in the thick of what you can barely handle, to those of you with toes already out over the edge on the precipice of unbelief, hear the good news: the God who came down to jump Jacob in the darkness of his guilt and sin— he sneaks up on you too.

He’s come down as low as he can go.

He’s no higher than a tabletop.

He’s right in front of you.

In loaf and cup.

He’s biding his time, waiting for you, with whatever struggle you’re wrestling, to grab hold of the graspable God.

Come to the table with whatever wounds or worries you are bearing and demand from him the blessing that is Christ Jesus himself.

The body and the blood— they are the edible promise, Christ’s last testament, that one day the Lord Jesus will say to you too, “You have struggled with God and prevailed…”

Because this is his body broken for you, because you have been baptized into his righteousness, one day Israel will be your name too.

Share this post