Miracles are not simply about divine power overcoming natural resistance; miracles are the revelation that nature itself is destined for transformation.

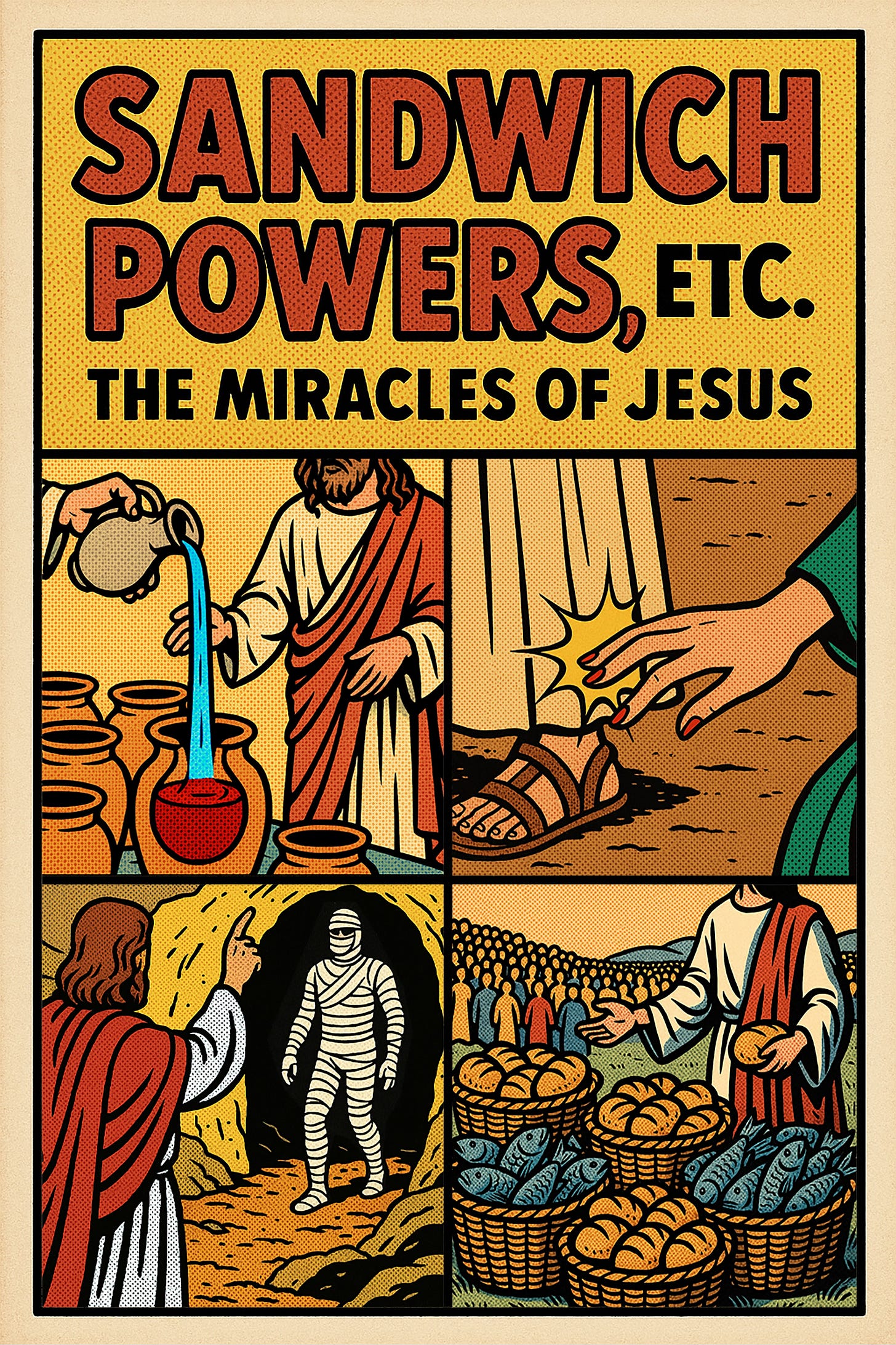

On Sunday, I began a long sermon series in which I will preach through the miracles of Jesus as recorded in the Gospels. In no small part, I want to help my hearers think theologically about the miraculous. My sense, after twenty-five years in ministry, is that believers tend to treat the New Testament’s miracle stories as narrative devices, non-literal illustrations or, as John frames them, signs that point to the identity of the LORD Jesus. But those same Christians have no qualms about submitting names for their church’s prayer list.

This is a problem.

For the problem of miracles just is the problem of prayer.

To petition the Father in prayer is nothing less than to ask for a miracle.

So I’ve been thinking about miracles.

Not everything in my notes thus far made it into Sunday’s sermon.

In an essay originally published in the journal First Things and now included in his book Revisionary Metaphysics, Robert Jenson asserts:

“In a world without stories, miracles are just anomalies.”

By stories, Jens means Story with a capital S. Without a narrative which posits an Author and so coherence to the events of history, time is just one damn thing after another and miracles are mistaken as random, fortuitous events. Without a meta- narrative, miracles are, at best, anomalies—events that appear to interrupt the normal course of nature but lack explanatory coherence. At worst, they are dismissed outright as premodern illusions or manipulations.

Thomas Jefferson, founder of my alma mater, exemplifies modern discomfort with the claims of the scriptures. Beginning in the Enlightenment, the modern world tends to view nature as a closed, autonomous system governed entirely by impersonal physical laws. Correlatively, the modern world— even the default Christianity of most modern believers— views God not unlike Jefferson’s distant Clockmaker, who having once created the universe now relates to it in a hands-off manner. Thus the God of most modern “belief” is immune to time; just so, the God of most modern “belief” is the god of the religion of Plato— immune to time. So understood, miracles are nothing less than divine intrusions into time.

Jenson cuts to the heart of this impasse.

Jenson insists that the problem of miracles (and thus petitionary prayer) is not with miracles per se, but with the modern world’s loss of narrative. For Jenson, creation is not a neutral arena of events, but a dramatized sequence authored by the triune God. Miracles are not exceptions to the world’s order, but disclosures of its true telos.

Since Jens lives rent-free in my head, readers will know already that central to his theological vision is the claim that God is identified by the story of Israel and Jesus. “The God of the gospel,” he writes, “is identified by and with the particular plotted sequence of events that make the narrative of Israel and her Christ.” For Jens, divine identity is not abstract or static; it is revealed narratively, as a movement from promise to fulfillment. This movement is not outside time but internal to it.

As he writes:

“God is not timeless. He is the one who keeps his promises.”

Put differently, the ontology of God is narrative; creation itself is storied.

Time is not the residue of past divine activity but the medium of God’s self-communication. If creation is storied, then miracles are no longer violations of the universe’s structure but its truthful appearances. “Miracles,” Jens writes, “are the intrusive visibility of the real world’s truth in a world that denies it.”

Far from being anomalous, the miraculous is revelatory.

Miracles, answers to prayer— they signal the in-breaking of the eschatological future, the Last Future where the Risen Jesus lives as its first resident, into the present. There is a reason he titles his book Revisionary Metaphysics. Jens’ claim that the world is a story stands in intentional conflict with the Enlightenment view of nature as a mechanistic system. Jefferson et al presumed a world of isolated causality, where the laws of physics and biology function deterministically; A.I., it should be noted, relies upon the very same view of creation— it assumes that Jesus is not alive so as to be able to surprise us.

But if Jesus is alive, then miracles are neither irrational nor intrusive, for the the world is not a closed system. If creation is teleologically shaped by the God who raised Jesus from the dead—then miracles are not anomalies but signs of the world’s actual grammar.

Jenson, as well as, for example, the theologian Sergius Bulgakov, regard the resurrection of Jesus Christ as the paradigmatic miracle. Easter is not merely one event among others; it is the climax of the divine narrative within history. “The resurrection,” Jens writes, “is the eschaton within history. It is God’s final word spoken early.” The resurrection reveals the world’s true End—reconciliation, not decay.

All other miracles— even those which precede it in Israel’s scriptures— participate in the miracle that is Resurrection.

As Bulgakov stresses:

“The resurrection is the triumph of the Holy Spirit, not as suspension of death’s law but as the unveiling of life’s deeper law.

The risen Christ discloses the world’s true End: not entropy, but theosis. All miracles, understood in this light, are akin to the Transfiguration: present-day anticipations of the Last Future.

Jenson thus reframes the meaning of miracle.

It is not simply about divine power overcoming natural resistance. It is the revelation that nature itself is destined for transformation. And this where the alleged problem of miracles is but the problem of petitionary prayer. They both rely upon providence. That is, miracles are not exceptions to divine governance; they are— in concentrated form— expressions of it.

As the providence of God made flesh, it is no wonder then that miracles follow Jesus as much as outbreaks of the Spirit.

For Jens, prayer is nothing less than participation in providence, and the miraculous is but the LORD’s response to our petition. Just so, miracles are integrally linked to human participation. Jens argues that prayer is not an attempt to influence an otherwise deterministic system— this is exactly how many Christians imagine prayer. Prayer is rather participation in the shaping of time by God.

He writes:

“To pray is to be drawn into God’s own providential ordering of time.”

In other words—

Because creation is storied, the world is governed not merely by causality but by promise.

As the people called to proclaim that gospel promise, the church is thus not simply the body that remembers miracles. She is the sphere in which miracles continue to occur.

Because the church knows the Story, she is the body who knows to notice miracles.

And to name them as such.

Starting with the ordinary miracles of loaf and cup, word and water.

As Jens puts it:

“The Church the miracle of time’s healing.”

The sacraments and the gospel word that attaches to them are reminders that miracles are not irrational intrusions into an impervious material order. They are manifestations of a deeper rationality—a divine logos that orders all things toward communion.

In a world with a Story, miracles are not anomalies.

They are announcements.

The Author is risen indeed.

And his Spirit yet speaks.

Stories are all we have, all that makes us and all we will leave in the world. Sharing stories, and thus participating in stories is God’s gift.

Which Jenson book (or paper?)