John 18:1-19:42

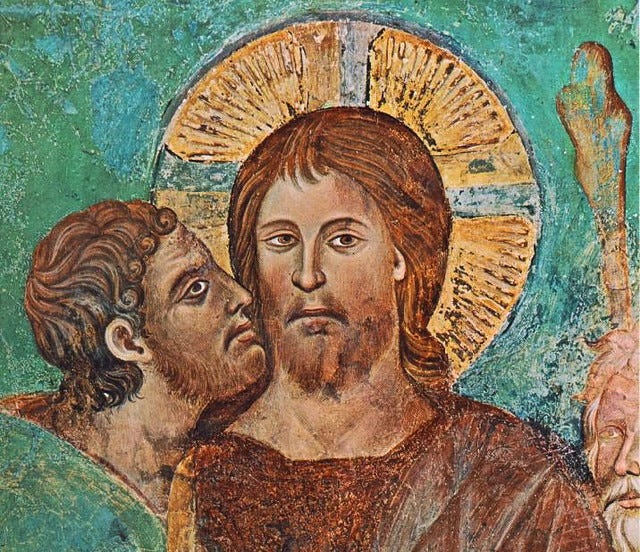

Two or three hours after Jesus washes the feet of his disciples, Judas leads a torch-carrying posse of religious officials to the garden of Gethsemane on the Mount of Olives where Jesus is praying.

“We’re looking for Jesus of Nazareth.”

Jesus responds with a self-attestation that is as stripped down and bare as he soon will be upon the cross.

“I AM,” announces.

And immediately, John reports, Judas and the lynch mob stumble backwards and fall to the ground.

They understand.

One is not bold in an encounter with God.

Perhaps Jesus’s incredible self-assertion is the reason that Judas repents of his act almost immediately and forthwith returns the blood money.

Judas does so before Jesus is even arraigned before Pilate.

Jesus had said very carefully at the beginning of the Gospel that he chose Judas knowing Judas would hand him over to his enemies. This stone that Judas sets to rolling is— strangely, simultaneously— the eternal will of God.

Judas hands Jesus over to the chief priests.

The chief priests hand Jesus over to the Gentiles.

The Gentiles hand Jesus over to Pontius Pilate.

Pontius Pilate hands Jesus over to the mob.

The mob hands Jesus over to the cross.

And in every link in the chain lies the Father handing over the Son.

From all eternity, God willed to let this assault be made upon him. Nevertheless, Judas’s disobedience is certainly not obedience. Judas’s name is honorific, an homage to Israel’s last mighty military leader and messianic candidate. His other name— Iscariot— suggests that Judas belonged to the Sicarii, a sect that agitated for the violent overthrow of the empire. The Sicarii were exactly the sort to find Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim a disappointing messiah. Judas determines to hand Jesus over the Saturday before in Bethany, just after Jesus lauds Mary for lavishing upon him a prodigal amount of costly nard.

The Gospel of John concentrates its indictment upon Judas but Matthew, Mark, and Luke make clear that all of the disciples recoil when Jesus praised Mary for glorifying Jesus— specifically, glorifying him in his death.

None of them want a crucified Lord.

Thus Judas merely actualizes a sin that was a possibility for them all.

Judas is the only apostle from the tribe of Judah— as is Jesus; thus, like Jesus, Judas represents all of Israel. Just so, Judas personifies all our rejection of God. But, “betray” is not quite the right word to describe Judas’s act. All during his final week, Jesus has come in and out of the city to teach at the temple. He’s not been hard to find. He’s hardly an anonymous figure. He’s not in need of identification. The chief priests did not require a traitor to finger the suspect. With Jerusalem teeming with Passover pilgrims and tense with revolutionary fervor, the chief priests simply sought an opportunity to arrest Jesus when such an arrest would not set off an uproar.

Judas informs them of such a time and place.

He’ll be in the garden. Late tonight. After the passover. Just a few with him.

And in response the chief priests immediately weigh thirty pieces of silver. It’s an odd amount to have at the ready until you recall that it’s the exact amount the prophet Zechariah associated with the price of a bad shepherd.

A bad shepherd— hence, Judas is not precisely against Jesus.

Rather Judas is not for Jesus in the way that Jesus demands of us if we are not, inadvertently, to be against him.

Mary glorifying Jesus in his death—

She is not exceptional.

She is what Jesus expects.

While Judas concluded to hand him over in Bethany, the chief priests first plot to kill Jesus after he raises Lazarus from the grave. At the soon-to-be-empty tomb, Jesus declared to the astonished onlookers, “I AM Resurrection and Life.”

And quickly Caiphas and the chief priests conclude:

“If we let him go on like this, everyone will believe in him, and the Romans will come and destroy both our holy place and our nation…It is better to have one man die for the people than to have the whole nation destroyed.”

In other words, their reasoning is that of Judas.

What good is a messiah if he’s only going to get himself crucified?

And us crucified with him?

He’ll be in the garden. Late tonight. Just a few with him.

At the Fall, in the garden, God went searching for Adam, whose sin had caused him to hide in shame. “Adam, where are you?” the Lord had asked. On the eve of redemption, sinful Adam comes searching for God who is hiding in plain sight, naked and unashamed, in a homeless carpenter. “We’re looking for Jesus of Nazareth,” we say.

After he walked on water, when Jesus taught in the temple and upset more than tables and cash registers, John reports that “No one was able to lay a hand on Jesus because his hour had not yet come.” But when his hour does come, when the handing over of Jesus by Judas leads these begrudgers through the darkness of night to the light of the world, Jesus voluntarily and deliberately gives himself up. The one who has preached peace does not resort to violence in order to resist them. He identifies himself.

No— he reveals himself.

“We’re looking for Jesus of Nazareth.”

“I AM,” announces.

And immediately, they stumble backwards to the ground.

“I AM.”

Ego eimi.

As Fleming Rutledge writes:

”This statement cannot be construed as anything other than a deliberate appropriation by Jesus of the name given by God to Moses from the burning bush. Therefore, precisely at the moment when his passion begins, Jesus unequivocally identifies himself as nothing less than the living presence of the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the creator of the universe, the Lord who is and who was and who is to come.”

Moses said to God, “Suppose I go to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ Then what shall I tell them?”

“Tell them I AM has sent you,” God says to Moses from the burning bush.

“We’ve been sent for Jesus of Nazareth,” we say.

“I AM,” says God.

Martin Luther compressed the mystery of this self-assertion by Jesus with the Latin phrase Finitum capax infiniti, “The finite is capable of containing the infinite.” The glory of God is camouflaged by humility and suffering, Luther said, for our God likes to hide himself beneath his opposite.

Of course this mystery also produces the absurdity of the Passion; that is, Judas et al are against the very God who is for them in Jesus Christ.

Then again, this mystery that produces the absurdity of Good Friday also begets the offense of the gospel; namely, Judas is the first of the sinners to save for whom Christ came in to the world.

Just the other day I typed into Google’s search engine the incomplete sentence, “God is…” and even before I was done typing Google autofilled the most common choices.

God is love.

God is good.

God is dead.

And then the next three:

God is in control.

God is just.

God is gracious

Good Friday is the only moment in time where all of those sentences are true statements.

But when I scrolled even further down the list of the most popular searches for the definition and identity of God not one of them said, “God is a crucified Jew who lived briefly, died violently, and rose unexpectedly.”

Ironically, our search history proves that Jesus did not die alone.

Judas too suffered death in place of others exactly to the extent that, like Judas, neither do we much want a crucified God.

As the Apostle Paul notes at the opening of his letter to the Romans, fallen humanity is fallen precisely in that we don’t want to know about the real God and his will. But on Good Friday we are without excuse. We know the real God, and he has told us more about his will for our lives than any of us are willing to obey, for the one who bears our sins in his body on the tree began his journey there by saying, “I AM.”

“We’re looking for Jesus of Nazareth.”

“I AM.”

True God from true God.

Begotten not made.

Of one being with the Father.

Nearly every account of something Jesus says or does in John’s Gospel ends with someone believing in Jesus. Believing not in the signs he performed or in the truths he spoke but purely and simply in him. When Jesus transforms water into almost two hundred gallons of top-shelf wine, the wedding at Cana doesn’t end with the partygoers exclaiming “Wow!” or looking forward to free Chardonnay forever. No, John says the disciples saw and believed in Jesus himself who is “the best wine kept until now.” When the man born blind sees Jesus for the first time, he says, “I believe.” Indeed John’s Gospel ends with Thomas testifying, “My Lord and my God.”

The only instance where Jesus says or does something in John’s Gospel that does not end with someone believing in Jesus is when Judas hands Jesus over to the chief priests’s posse. After stumbling backwards and falling to the ground, Judas runs away. He returns the thirty pieces of silver to the ones who bought him. And then he enters a passion of his own in a place the priests later named Akeldama, Field of Blood [Money].

Where Jesus gives up his life upon a tree, Judas takes his life upon a tree.

Where Jesus surrenders his life believing the Father will vindicate him, Judas forsakes his life upon a tree believing there was no longer any hope for him.

Where Judas usurps the role of Judge over his life, Jesus submits to being the Judge judged in our place.

Nevertheless, Karl Barth writes, Judas, though he may not fathom it, “is still an elect and called apostle of Jesus the Christ.” If Jesus comes to save the lost— and there is no one in the Gospel stories who is more lost than the one who betrays God for the modern day equivalent of $216— then surely the saving grace of God would include even Judas! If the shepherd goes to any length to save the single lost sheep, if the widow lights a lamp in the middle of the night to find a lost coin, and if a father joyfully celebrates the return of the prodigal, then surely, Barth insists, Judas is not out of reach for the One who has come to save us all.

According to Barth, after Christ himself, Judas is the most important character in the New Testament because Judas is the executor of the New Testament.

He is the executor in that he wills what God wills to be done.

As Barth writes:

“The paradox in the figure of Judas is that, although his actions as the executor of the New Testament is so absolutely sinful, yet as such, in all its sinfulness, it is still the action of that executor. The divine and human handing over cannot be distinguished in what Judas did…in the case of Judas, sin is made righteousness and evil good…Was it not Judas, the sinner without equal, who offered himself at the decisive moment to carry out the will of God, not in spite of his unparalleled sin, but in it? There is nothing here to venerate, nor is there anything to despise. There is place only for the recognition and adoration and magnifying of God.”

In fact, Judas on his tree, utterly lost and without merit of any kind, becomes an icon of the merciful depths of the crucified love on Calvary’s tree. The love that is God is crucified love even— especially— for him.

And if for him, for you.

Ultimately, in handing Jesus over, this is what Judas took upon his conscience— to bring Jesus into the situation where apart from the Father no one can help Jesus. In handing Jesus over, Judas perverts his office as an apostle into its exact opposite. Rather than bringing sinners under the power of Jesus, he’s delivered Jesus into the hands of sinners.

Nevertheless!

As Barth writes:

“It is a serious matter to be a Pharaoh, a Saul, a Judas…a sinner…but whatever judgment God may inflict on Judas, God certainly does not inflict on Judas what God inflicted upon himself by handing over Jesus Christ.”

“We’re looking for Jesus of Nazareth.”

“I AM,” Jesus replies.

“So the soldiers, their officer, and the Jewish police arrested Jesus and bound him,” John concludes, “…and they handed him over to Caiaphas, the high priest that year, who was the one that had advised the Jews that it was better to have one man die than for all to die.” Only Easter can reveal the irony: Caiaphas is correct. “Because the one man died for all,” Paul writes long before John writes his Gospel, “all have died.”

The divine and human handing over cannot be distinguished.

Therefore—

In Jesus’s death, the Judas in Judas dies.

In Jesus’s death, the Peter in Peter dies.

In Christ’s death, the Judas in you dies.

In Jesus’s death, the Peter and the Pilate in you die too.

Because by water and the word, YOU ARE in him who says, “I AM.”

The promise alone should make you shudder and stumble backwards.

For the news itself of Christ and him crucified is an encounter with the One who will raise him the dead.

Share this post