Transfiguration Sunday — 1 Kings 19.1-6 & Mark 9.2-9

The last time I preached through the Book of Kings and preached on Ahab and Jezebel’s violent regime was during our second war in Iraq. It was during Lent and in the sermon the Lord summoned me to speak a word about the use of state-sponsored torture. Newspapers had only recently begun reporting on the Torture Memos which documented the ghastly abuses by at the prison in Abu Ghraib. The images outraged the world.

In the face of such revelations, the churches in America were silent.

I was young and brash and preached what I took to be self-evident.

“Why is the church in America so quiet these days?” I exhorted my hearers.

I let question linger for an uncomfortably long silence before I continued:

“Why are Christians so quiet about this particular issue? What is the matter with us? The left wing of the church is preoccupied with homosexuality and the right wing of the church is consumed by abortion. Why is this? Has the church lost its nerve? Has the church forsaken the scriptures? Has the church forgotten we worship a crucified Lord?

No matter what a person has done or is suspected of doing, once that person is taken into custody, he or she becomes defenseless. The Old and New Testaments alike are clear: abuse of a defenseless person is an abomination in God’s sight. The defenselessness of a fetus is a central argument advanced against abortion.

This conviction about defending the defenseless lies at the very heart of our faith. Yet we are silent, as quiet as all his followers who did not shout, “Do not crucify him!”

It may not have been the most prudent word to preach. Or sensitive.

But it was true.

Therefore it was God’s word.

And God’s word, scripture says, not only makes alive but kills.

The word of the Lord that Sunday morning struck a blow.

It disturbed the “peace.”

As soon as I handed over the benediction, a church member assaulted me in the narthex and, sticking his finger in my chest, hollered at me, “Just where do you get off preaching like that, preacher?!”

I stammered.

“Well, Senator,” I said, “It is Lent and the Lord was tortured to death.”

The Chair of the Armed Services Committee shook his head and waved his finger at me.

“You tell me, preacher— if Jesus was still alive, do you honestly think he’d having anything to say about torture and the government?!”

“Um, well Senator, uh…I mean, he was crucified, I think...um...maybe he would have...” I started to say.

He shook his head and waved me off.

“Jesus would be rolling over in his grave if he knew you’d brought politics into our church! Just where did you get the idea that politics has any place in the pulpit?!”

“He doesn’t have a grave…it’s empty…” I muttered to myself.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“Never mind,” I said.

He stood there, his hands on his hips, dandruff on his shoulders, waiting for me to answers.

Finally, he repeated his question, “Where did you get the idea that politics has any place in the pulpit?!”

I stammered, “Uh, it’s called the Book of Kings.”

He thought I was being cute.

“You better watch out!” he threatened, “I could have you run out of this place!” And then he shook his now crimson head, motioned for his wife to catch up to him, and then he hurried off.

A few weeks after, on Easter Sunday, when he arrived, opened up the worship bulletin and saw that I was the preacher, he turned right around and left the way he had come. I wasn’t the only one who noticed, and I was made aware of the damage I had wreaked. Later, I left and went home, feeling not a little sorry for myself and ruing a calling I had not chosen but nevertheless could not shake.

For a brief moment, it appears God’s wayward Israel is back on track.

The word that struck like a fever into the heart of the earth has broken and the judgment that had parched the promised land for three years is over. The barren deity Baal has been disgraced and his false prophets have been dispatched. Ahab has departed from Mt. Carmel, with the Man of God running out ahead of him as a herald of Israel’s king and the Lord’s covenant with Israel renewed.

Alas, the very same word of the Lord that had induced faith in Israel, “Yahweh indeed is God; Yahweh indeed is God,” arouses opposition from Israel’s queen.

Like Pharaoh before Moses, when she learns what Yahweh has done, Jezebel’s heart hardens.

Realizing she’s on the wrong side of the true and living God’s work in the world, Jezebel neither repents nor relents. She resorts to wrath.

Whether or not the Lord is responsible for the slaughter of the four hundred and fifty prophets false prophets, Jezebel clearly believes she has been addressed by Yahweh in the killing of her prophets.

The Lord’s word to her is the piece of news that propels her act.

And Jezebel vows to make Elijah one of the corpses floating in the wadi, a brook flowing red with blood.

No sooner has success come to the Man of God than God’s enemies pick a fight with him.

Commenting on this passage and comparing it the similarly hostile reactions to the ministries of Jesus of Nazareth and the apostle Paul, the Reformed theologian Peter Leithart asks:

“Why do the church’s enemies have to pick a fight just when things get rolling?”

“The answer,” Leithart insists, “is they don’t. The church does.”

The church’s enemies need not pick a fight.

But the church must always pick a fight.

Peter Leithart writes:

“Jesus does not come to bring peace but a sword, to set brother against brother, mother against daughter, [senator against preacher].

Following its master, the church likewise provokes the hostility, hatred, and resentment of the world at every turn. This is not the result of some flaw in the church’s ministry, but the opposite.

When the church is faithful, it announces judgment of this world (John 12:31), the universal corruption and disorder of humanity (Rom. 1:18–32), and the overthrow of the prince of this world (John 16.11).

We do not need Nietzsche to tell us that we are dominated by lies and violence, motivated by pride, envy, lust, wrath, and vengefulness. We do not need Foucault to teach us that the world languishes under the dominion of the dark powers, principalities, and wickedness in high places. [We do not need Critical Theory to teach us that our systems and institutions are not immune from the contagion of original sin.]

We proclaim Christ and him crucified. Inherent in the gospel is the condemnation of this world, and when we preach such a gospel, we cannot help but pick a fight.”

We cannot help but pick a fight.

Notice—

Jezebel’s actions are neither surprising nor instigative.

Jezebel’s actions are not even actions.

Jezebel’s actions are really reactions.

Elijah is the aggressor.

Like Elijah the Troubler of Israel, the church is an aggressor, if and when we refuse to be silent and proclaim the gospel that is at once the judgment of “this present evil age.”

Present evil age— that’s how Jesus describes the world that tortures him.

As Peter Leithart puts it:

The church does mean to do harm to unbelief, to injustice, and to wickedness. The church does mean to do harm, casting down every vain imagination and defeating every thought that exalts itself above Christ Jesus. The church does mean to do harm, by proclaiming the gospel until every knee bows down in surrender to Jesus Christ the Lord.

The gospel is the opposite of the Hippocratic oath!

We mean to do harm.

When we do not forget our baptisms, followers of Jesus are no less irksome than the Troubler of Israel.

Years after he accosted me in the narthex, he came to me, inquiring about baptism. The Lord had not saved him through water and the Spirit, and he was at an age where it nagged at him. In the intervening years, I’d grown on him and he had learned to trust me.

We were talking about baptism in my office, my print of Karl Barth before an empty tomb hanging behind his head, when all of a sudden he changed the subject.

He took off his glasses.

He rubbed his bald head with his sleeve.

And he said, “All those years ago, when I got angry with you for your (he struggled still to call it such) sermon. You let me walk away. You didn’t pursue me or follow up with me. Why?”

And this time I was sitting but I resumed my stammering, “Uh…”

He shook his head and put his elbows on his knees, leaning forward.

“Was what you said about the Bible true?” he asked me.

“Yes,” I think so— I mean, I believe so.

He nodded like I was a witness in a committee hearing.

“And was what you preached about Jesus true?”

I nodded.

“Then why for God’s sake did you let me walk away?”

I felt cheeks flush red.

“I was…I was afraid…”

He smiled graciously and filled in the blank, “You were afraid to pick a fight with a senator.”

I shrugged my shoulders in submission.

“Well, take it from a politician. There’s nothing that’s true that’s not worth fighting over.”

I nodded, not accustomed to being on the receiving end of a sermon.

“And if it’s a matter of ultimate, eternal truth,” he said, looking at the carpet, “Well, then, I expect you should speak as plainly and fight as indecently as you know how.”

Inherent in the gospel is the condemnation of this world, and when we preach such a gospel, we cannot help but pick a fight.

Benjamin Lay was a seventeenth century Christian, whom popular history has forgotten. A dissenter and a strategic practitioner of incivility, Lay was an English commoner who traveled the world as a sailor.

Afflicted with kyphosis, Lay stood barely beyond four feet tall.

Yet his stature did not stand in the way of his witness.

In particular, Lay agitated against slavery and the “false ministers” who tolerated or defended the practice. At church, Lay would start arguments with preachers in the middle of their sermons.

A letter sent from his church in London to a church in Philadelphia, where he was booked to speak, accused him of “Indiscreet Zeal.”

As a sailor, he and his wife had been banished from Barbados for denouncing the sugar industry and inviting the slaves who enabled it to dinner at his family table.

On September 19, 1738, Lay attended a worship service in Philadelphia.

He smuggled into the service a military uniform, a sword, and a Bible that he’d rigged for a prophetic purpose.

In the middle of the preacher’s milquetoast sermon, Benjamin Lay stood up and shouted that God loved all people equally, regardless of how sinners sought to interpret his word.

Lay then threw off his cloak, revealing his hidden tools.

He proclaimed, “Thus shall God shed the blood of those persons who discriminate against their fellow creatures.”

Then he stabbed the Bible he had brought with the sword had had carried under his cloak.

Only Lay had hollowed out the pages of the Bible and placed in the pocket a pig’s bladder filled with pokeberry juice.

Thus when he proclaimed the word of the Lord, he simultaneously splattered blood on the slave keepers and their apologists.

As one historian remarks:

“As long as Christians owned slaves, there would be no business as usual if Benjamin could help it. His brothers and sisters in Christ had made peace with the devil, so he used his body to disrupt their hypocritical, pious routines.”

In other words, he knew that if the gospel is a promise of God’s Future then likewise is it a judgment on our present.

And so the dwarf practiced indiscrete zeal.

The day before his trial for picking a fight in Birmingham, Alabama, Martin Luther King Jr. preached at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. The violence that would be unleashed on the Freedom Riders in Alabama was a reaction. Those bearing the word of God were the aggressors.

Acknowledging such, King addressed concerns that his witness had upset “the peace and civility of the community.”

In his sermon at Dexter Avenue, King proclaimed provocatively:

”If peace means accepting second class citizenship, I don't want it. If peace means keeping my mouth shut in the midst of injustice and evil, I don’t want it. If peace means being complacently adjusted to a deadening status quo, I don’t want peace. If peace means a willingness to be exploited economically, dominated politically, humiliated and segregated, I don’t want peace. So, in a passive, non-violent manner, we must revolt against this peace.”

The judge who found King guilty suggested in the sentencing that King’s manner of witness was indecent for a Christian.

Between Benjamin Lay and MLK is two hundred and eighteen years.

Between both of them and Mary’s boy is nearly two millennia.

And between Dr. King and you and me is still nearly seven decades.

In other words, God’s drafted us into a battle that is bigger than us.

Once Elijah’s aggression sets Jezebel’s hatred in motion, the Troubler of Israel retreats beyond Jezebel’s reach, to the southernmost edge of the Kingdom of Judah.

Sitting under a solitary desert tree, Elijah despairs. Elijah under the broom tree sounds exactly like Jesus in Gethsemane.

“Remain here with me…for I am so depressed I could die,” Jesus begs the disciples in the garden on the night he’s handed over to be tortured.

This correlation should not surprise us.

Our passage displays not simply a clash between two fierce wills, Elijah versus Jezebel, but a conflict between two mighty powers, the power of Almighty God versus the power that is Not God.

As the Dutch biblical scholar, M.B. Van’t Veer writes:

“Jezebel is a prototype of the ancient opposition between God and Satan. This opposition receives its concrete exemplification in these two people of flesh and blood, in whose life the powers from above and the powers from the abyss are manifested. Their struggle forms part of the one great struggle.”

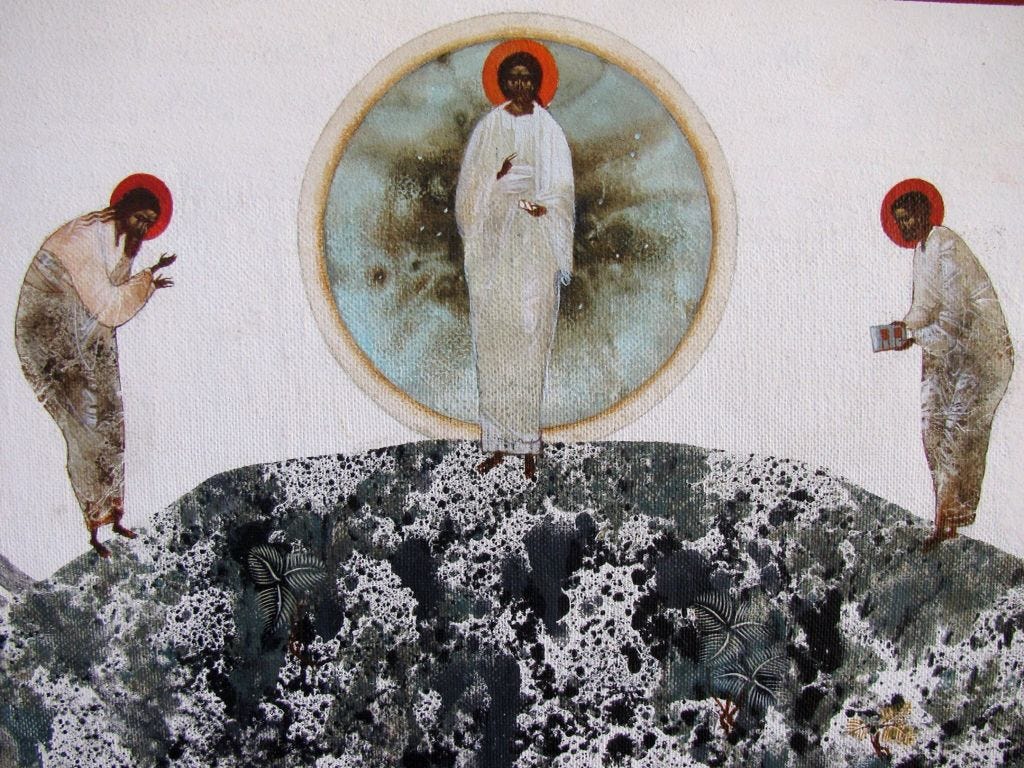

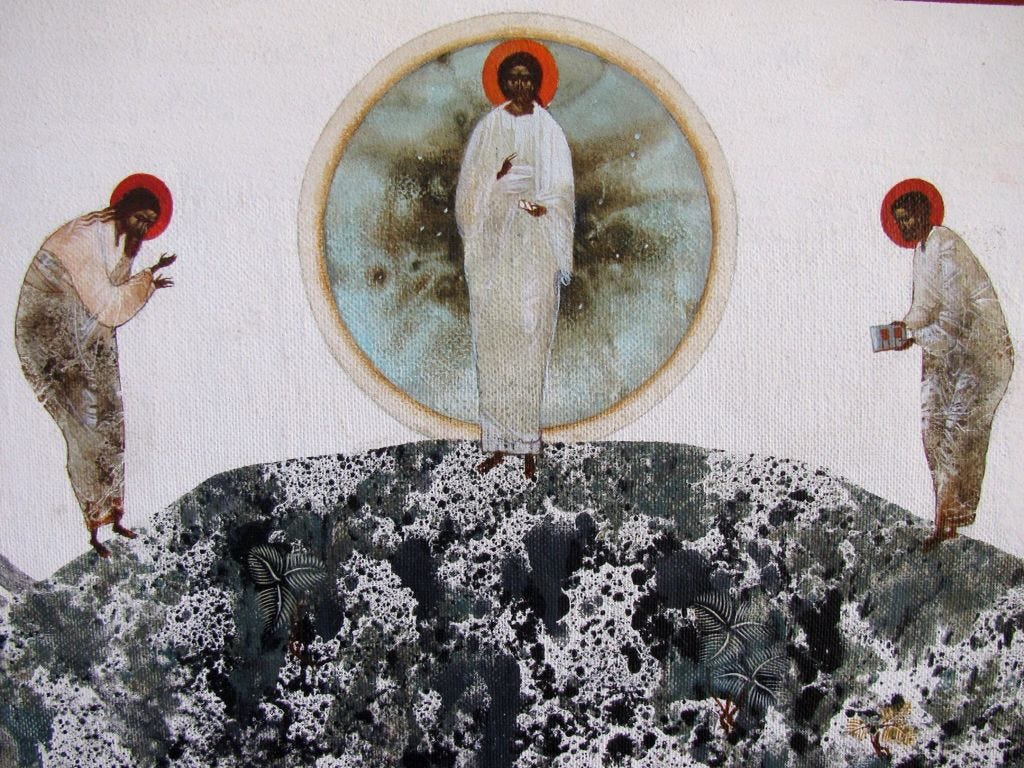

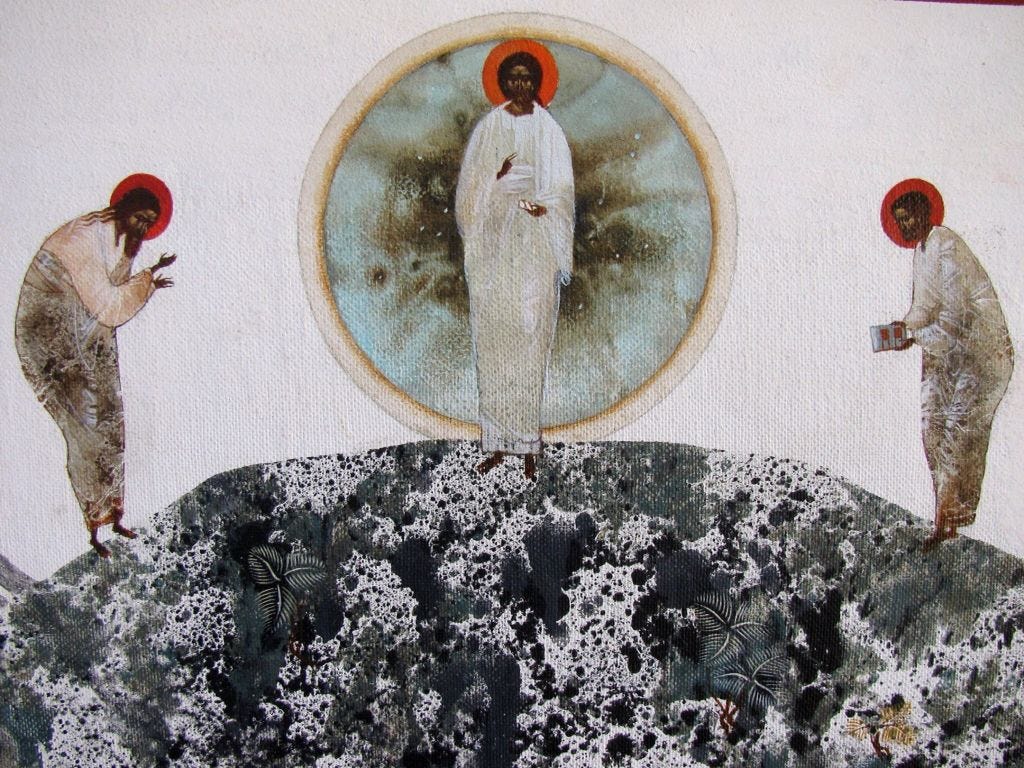

Surprisingly, the clash between Elijah and Jezebel, the opposition between Almighty God and his Enemy, is the conflict the Gospel of Mark shows you on the Mount of Transfiguration.

Typically, interpreters will suggest that Moses and Elijah represent the law and the prophets and thus Jesus is the summation of Israel’s scriptures.

But as common an interpretation as that is, it doesn’t square with how Israel read her own scriptures.

In the Old Testament Moses is only secondarily the receiver of the law; in the Old Testament Moses is primarily the prophet.

And for that matter, Elijah is not really a prophet.

No book of the Bible bears his name. Kings only refers to him as a prophet once, calling him instead the “Man of God,” and the “Troubler of Israel.” Once again, Moses represents the prophets not the law. And Elijah is not even a proper prophet. So the “law and the prophets” slogan is not the correct takeaway from the Transfiguration.

Rather than each representing a different feature of Israel’s scriptures, they both share Israel’s exclusive vocation.

Moses and Elijah both picked fights.

They are both Troublers of Israel.

Moses went before Pharaoh bearing the word of the Lord, “Thus says Yahweh the God of the Hebrews: “Let my people go, that they may serve me.

Elijah appears in Ahab’s council bearing a similar word, “As the Lord the God of Israel lives, before whom I stand, there shall be neither dew nor rain these years, except by my word.”

Moses and Elijah do not summarize all the law and the prophets. They represent the single battle the Lord wages against the Enemy, whom Jesus names “the Prince of this world,” whom Paul calls the Powers of Sin and Death, and whom Peter labels the Adversary.

The Devil.

To his credit, Peter understands what he sees on the Mount of Transfiguration.

With the two Troublers of Israel beside him, Jesus, who is soon to get himself crucified, is ablaze with the glory of God.

Peter responds by suggesting they build three tabernacles, booths— a reference to Sukkoth, a harvest festival that in Peter’s day anticipated the eschatological harvest.

Seeing Christ transfigured, Peter knows he’s seeing Jesus as he will appear at the end of the age when Christ, as Paul writes, will “deliver the kingdom to God the Father after destroying every rule and every authority and every power… and put all his enemies under his feet…”

Peter suggests building booths because he’s just seen the end of the battle begun in Moses and Elijah.

Peter suggests building booths because he knows the Man in the Middle is the last Troubler of Israel.

Peter suggests booths because he understands that he’s just glimpsed the one who will finish the fight.

Peter’s only mistake is thinking the victory can come apart from the cross.

And our bearing the word of it.

There’s nothing that’s true that’s not worth fighting over.

After he delivered his small sermon to me, I taught the senator the theology of baptism, including that line about renouncing the spiritual forces of wickedness.

“If that’s true,” he said, “then the fight is even bigger than I ever imagined.”

He chuckled as he said it.

But his face belied the laugh.

“I suppose baptism means I’m called to be as irritating as I find you sometimes,” he said and then paused in the middle of his thought, like he was thinking about the wake that would come with the water.

“I’m a politician,” he said and threw out his arms like we were haggling and far past his limit, “Silence is courageous. How can I possibly be so truthful as to pick a fight?”

“No offense,” I replied, “but knowing you— it’s not likely. It’s damn near impossible, I’d say. But with God, who knows? Maybe you’re part of the all in “all things are possible for God.””

Maybe the Lord is able to make us bolder than we can bear.

Share this post