I continued our Lenten sermon series on the Seven Sorrows of Mary with John 19.17-27.

Nine years ago, during the first Trump term, I preached on the scripture assigned to me from the beginning of the Book of Exodus. There in the first chapter of Exodus Moses reports that a new pharaoh ascends to the White House, a president who does not know the previous administration’s advisor— Isaac’s son, the dreamer Joseph. Observing the rapid birth rate of these refugees who’ve crossed over the border from Israel, Pharaoh posits the first great replacement theory. He frets these immigrants will soon replace Egypt’s natural born citizenry. Hoping to induce them to self-deport, Pharaoh first inflicts upon the Hebrew immigrants harsh labor. Later, when harsh labor does not remedy the perceived dilemma, Pharaoh resorts to infanticide, “The king of Egypt said to the Hebrew midwives, one of whom was named Shiphrah and the other Puah, “When you serve as midwife to the Hebrew women and see them on the birthstool, if it is a boy, you shall kill him.”

Armed with such a pregnant passage, I stepped into the pulpit on the twenty-fourth of September and, straightaway into my sermon, I punched down.

No sooner had I engaged in a quick bit of exegesis than I pivoted to the present day, wielding the scripture passage as a pretext to excoriate the new president’s draconian immigration policies. I struck a prophetic posture. I opened the vent on the fire and brimstone. I laid down the law. Specifically, I exhorted my hearers to heed the LORD’s commandment to Moses on Mount Sinai, “When an immigrant sojourns with you in your land, you shall not do him any wrong. You shall treat the immigrant among you as a native-born, and you shall love him as yourself, for once you were aliens in the land of Egypt.” Now notice— in my selective sermonizing I neglected to mention abortion, an issue every bit as front and center at the beginning of Exodus as immigration.

I concluded the sermon with the If/Then, Either/Or conditionality that is the hallmark of the law. And remember— the law, scripture says, only always accuses. The law elicits only the opposite of its intent; it does not create the righteousness it demands. Nevertheless, I mistakenly preached as though my listeners had free will. “Either serve the LORD Jesus Christ and welcome the immigrant,” I preached, “Or ship them out— detain them, deport them, separate them, mother from child— and, by doing so, serve the Pharaohs who crucify the LORD anew.” “Choose this day whom you will serve,” I hollered, “You’re either on the side of the crucified, or you’re on the side of those who build crosses.”

To close, I even borrowed a quote from Peter Marshall’s famous sermon on Elijah versus the prophets of Baal, “Trial By Fire.” “If Jesus be LORD, then follow him,” I preached, “but if the President be Lord, follow him, and go to hell!”

And then I walked out of the pulpit as though it was a mic-drop moment.

Admittedly, in hindsight, it was a little heavy-handed.

But to be honest, initially I judged it a good sermon. Of course, I thought it was a good sermon because my listeners— that is, the ones who already agreed with me on the issue— told me it was a good sermon. A sure sign I had decided what to preach before I ever listened for the Word of God to have its way with me.

In other words, I had attempted to twist Jesus to my own ends.

“Standing by the cross of Jesus were Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene, and his Mother Mary.”

The Mother of the LORD does not ask for the life that alights upon her at the annunciation. Nevertheless, Mary says “Yes” to God”s “Yes” to lost humanity. To the angel Gabriel’s intrusive announcement, Mary replies, “Behold a slave of the LORD; let it be with me according to your Word.” Miraculously— full of grace—Mary manages to say “Yes” to the Triune God’s “Yes” to us. For that matter, Mother Mary seems never at a loss for words. When Mary retreats to Elizabeth’s house to ponder the mystery of the incarnation and thereupon her cousin addresses her, “Blessed are you among all women,” Mary immediately strikes upon words for the occasion. Mary sings, “My soul proclaims the Lord’s greatness, And my spirit rejoices in God my savior…”

When Jesus inaugurates his ministry at a wedding in Cana of Galilee and soon thereafter the father of the bridegroom runs out of wine, Mary does not hesitate. Words do not fail her; immediately she turns to the servants of the host and commands them, “Do whatever he tells you.” When the Pharisees and the scribes up the ante and turn the gears of their plot against her boy, demanding from him a sign, Jesus replies caustically, “A wicked and adulterous generation seeks a sign and a sign shall not be given it.” No stranger to danger, Mary risks her son’s rebuke and intervenes, sending for him to return home.

Once her unasked for life arrives, Mary is no more a passive victim than her boy. At every turn, Mary always knows what to say. Or, not to say.

Not only does Mary say “Yes” to God’s “Yes” to us, Mary does not say “No” to God’s “No” to humanity’s lostness.

As Jesus utters his seven last words from the cross, Mary does not offer a single one.

Indeed beginning with the day she relinquishes him at temple, handing him over to the Father, the only person to accept Jesus on his own terms is his Mother.

On that Sunday in September, Charlotte Rexroad lingered in the narthex after worship.

Charlotte had been the chair of the Staff-Parish Relations Committee when the bishop appointed me to the church eleven years earlier. At the mandated “Meet the Pastor” encounter, Charlotte dressed like Jackie Onassis, wearing a vintage, soft turquoise suit. Soon after, I learned that it was not a costume. Charlotte was proper and dignified and astonishingly empathetic.

After I went on medical leave for my first bout with cancer ten years ago, Charlotte brought me lunch every Wednesday. Every week she made me a homemade Rachel sandwich— like a Rueben but with chicken breast— along with chips, a pickle, and a bottle of Thousand Island Dressing. It was not long before I had more bottles of the salad dressing in my refrigerator than chemotherapy drugs. Charlotte had organized a baby shower when we adopted our first son, Gabriel. Charlotte engaged every Bible study I taught like her GPA teetered on the precipice and a diploma hung in the balance. The Word were words of life for her.

Jesus was as real to Charlotte as the forty-eight bottles of Thousand Island she had brought to my house. She often disaffiliated from women’s prayer circles, chagrined such groups did little actual praying.

If ever I have met a human creature being fashioned into God, it was her.

She possessed a forthrightness made possible by her faith. I know so because that Sunday nine years ago her candor cut me to the quick. The law kills. And having laid down the law, Charlotte applied it in kind. She loved me. But— thank God—she loved Jesus more than me. Hence, she risked speaking the truth.

Charlotte was too polite and respectful to shame me in front of onlookers. Only after the crowd had petered out, did she approach me. She gave me a tight, fierce hug and a gentle kiss on my cheek. She patted her hands on the stole against my chest and then she put her hands on my elbows and bore holes in my eyes.

“Well, reverend, you certainly preached the gospel out of that sermon,” she said softly.

Confusion creased my brows, “Um, thank you.”

“It was not a compliment.”

They were just five words.

But they stung me.

“Tell me,” she said, “Maybe I was visiting my son in New Jersey and missed it. Exactly which Sunday during the previous administration did you preach that sermon? Certainly you must have preached a similar sermon because— as I’m sure you’re aware— that president started family separations and deported more people than this president.”

“I didn’t realize you were a supporter of…” I mumbled, sweat starting to bead on across my head.

“I’m not,” she corrected me, “I guess I’m an independent these days. But I’m definitely partisan when it comes Jesus. And today, whether or not what you said happened to be true or biblical, it sure sounded like you were using Jesus for your own project rather than pointing us to him and his work.”

In the Gospel of Luke, just after the devil tempts him in the wilderness for forty days, Jesus returns home to Nazareth to preach his first sermon. Jesus announces that the prophet Isaiah’s promise is fulfilled in him; the LORD’s covenant blessings will extend beyond his people Israel even to the ungodly Gentiles. Those in the synagogue respond by attempting to toss Jesus to his death.

If Jesus will not abet their worldview, they will not abide him.

In the Gospel of Matthew, just before he enters Jerusalem triumphant to a king’s welcome, the mother of the sons of Zebedee sees in Jesus’ impending reign an opportunity for her boys and so for herself. She braces Jesus with a request, “Say that in your Kingdom these two sons of mine may sit one on your right and one on your left.”

She sees in Jesus only what he can do for them.

When Jesus gives the twelve disciples power and authority over the demons, those same two “sons of thunder,” James and John, see in such privilege only the opportunity to manipulate the power of Jesus to settle an old grudge between the kingdoms of the North and South. “Lord,” they ask Jesus, “May we command fire to descend from heaven and to destroy them?”

They find in Jesus a tool for the preexisting partisan acrimony.

After Jesus’ temple tantrum, Judas’ betrayal is not outright treachery so much as an attempt to fit Jesus to Judas’ own agenda, forcing Jesus to act violently against the unjust temple system.

Rather than being with Jesus to the end, Judas attempts to manipulate Jesus to his own preconceived ends.

Even Pontius Pilate initially refuses to condemn Jesus. Pilate resists Christ’s condemnation not because Pilate is a righteous man but because Caiaphas seeks to extract such a sentence from Pilate. And Pilate insists on reminding the chief priest who the boss is in Jerusalem.

Caiphas and Pilate simply view Jesus as a pawn in their power struggle.

Even Peter! At the Transfiguration, on Holy Thursday, and just after the LORD calls him to follow, Peter does not want a crucified messiah. Peter wants only a Christ who conforms to his expectations.

Like Jonah attempting to flee from the God who dispatches him to hated Nineveh, in the end every last person in the gospels attempts to turn Jesus to their own ends. In spite of the fact Jesus is never for a moment in their power. In the Gospel of John, Jesus does not pray in Gethsemane for the cup to pass him. Jesus instead asks in the garden, “What shall I say? “Father save me from this hour”? No, for this purpose I have come to this hour.”

Though he appears to be a victim, beaten and spat upon and led to his execution, in reality Jesus is turning— through his voluntary self-offering— the destruction of his body the temple into the act of raising it up.

And Mary alone is his accomplice.

In the end every last person in the gospels attempts to turn Jesus to their own ends.

Everybody but his Mother.

That is, Mary assents to and cooperates with the End elected by the Son. Mary does not say “No” to God’s “No” to sinful humanity. The Son suffers at the command of his own divine will and none other, but his Mother does not resist. She does not say “No” to the cross.

On Good Friday, Mary does not shout, “Do NOT crucify him!”

Mary never pleads, “Do not crucify him!”

For the first time in her vocation, Mary does not speak. It is as if her silence, like Simon of Cyrene, helps her son to carry his cross. In fact, neither mother nor child utter any words along the Via Dolorosa, as though the pain and the urgency and the effort of the Road of Sorrows is their shared labor.

Just as Jesus contains in himself the coincidence of opposites, so too is the work of salvation both human and divine, the mutual labor of the Son with his Mother.

Elizaveta Pilenko was born in 1891 along the Black Sea in the Russian Empire. Her parents were devout Christians and raised their daughter such that, as a child, she emptied out her piggy-bank to contribute to the painting of an icon of the Mother of God for her family’s church. When she was a teenager, Elizaveta’s father died unexpectedly, a tragedy which twisted her faith into atheism. In 1910, Elizaveta married a Bolshevik activist who introduced her to a community of artists and poets and writers. To her surprise, among their many discussion topics, the group often talked theology.

Miraculously, her faith returned.

As godless communism consumed her country, Elizaveta secretly wore lead weights sewn into a hidden belt as a way of reminding herself "that Christ exists.” She joined an Orthodox Christian group, the Russian Student Christian Movement in 1923 and soon began to write on theology and the lives of the saints. A refugee in Paris, in 1932 the theologian Father Sergei Bulgakov consecrated Elizaveta as a nun in the Russian Orthodox Church. In taking her monastic vows, she chose for herself the name of the LORD’s Mother.

Mother Maria of Paris refused to flee to safety for America when the Germans invaded France in 1939. "If the Germans take Paris, I shall stay here with my orphans and old women,” she replied to entreaties, “The end is not mine to choose; I must follow Christ wherever he leads me.” A year later, in addition to smuggling children out of the country in trash cans, Mother Maria of Paris conspired with her priest-in-charge to provide certificates of baptism for Russian Jews hoping to avoid the camps. Nazis arrested her a year later and sent her to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Only a month before the camp was liberated, she was executed when she insisted the guards take her life in place of a Jewish child.

Deaf to the pleas for common sense, Mother Maria responded, “It is not for me to turn the LORD Jesus to my preferred end. This path is none other than his labor to which he enjoins us to share.”

Before she was martyred, Mother Maria authored an essay on her namesake, in which she wrote:

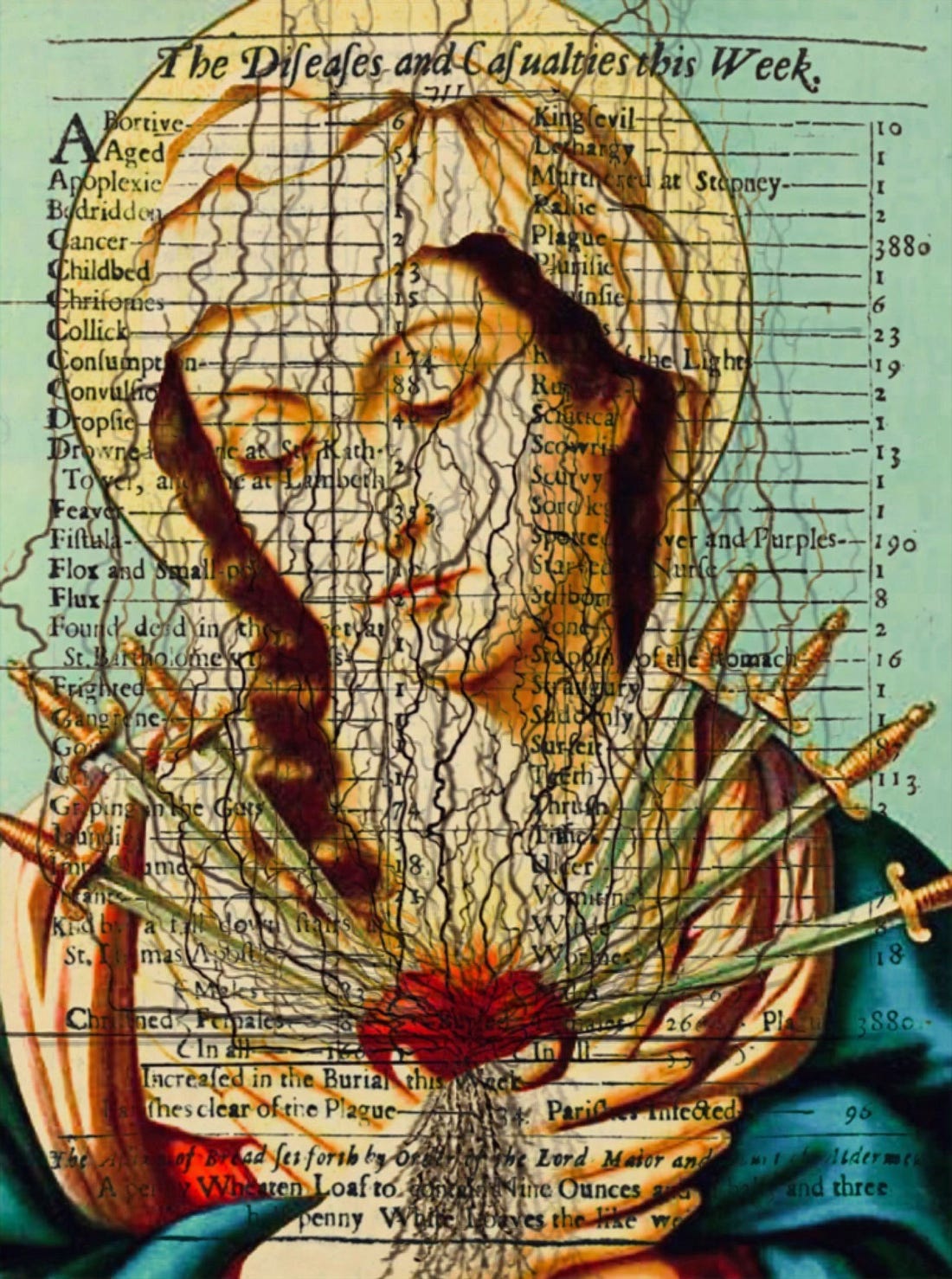

“The cross of the Son of Man, voluntarily accepted, becomes the doubled-edged sword transfixing the soul of his Mother, not only because she voluntarily choose it, but because she cannot not suffer the sufferings of her son... He undergoes the voluntary sufferings on the cross, she co-suffers with him. She co-participates. She co-feels, co-suffers. She is co- crucified… The whole mystery of Mary is in this co-uniting with the work of her son…”

I recently spent ten days in Asia Minor, following in the footsteps of Paul’s missionary journey, exploring the apostolic churches of the New Testament, and visiting the Byzantine basilicas where the ancient church fathers formulated the ecumenical creeds which govern us today. Across all those sites, which span centuries, I saw shockingly few crosses and zero depictions of the crucifixion. There were many icons of the Triune God at table with Abraham and Sarah. There were abundant images of Mary with child, and there were still others of Christ the Cosmic Judge. There were even several Anastasis icons, images of the Risen Christ yanking the dead by their forearms up through doors of Hades.

But there were no icons of the crucifixion of the LORD.

And the reason is simple.

For the first millennia of the faith, the Passion was the climax of Christ’s labor but it was not itself the central redemptive event.

For the ancient fathers and the first Christians the Son’s saving work was not his suffering and death but his faithful and obedient life lived unto death— even death upon a cross. This is nothing other than what the apostle Paul writes to the Colossians— that when the Father delivers the crucified Son from the tomb, as though from a womb, Christ becomes the firstborn of a new creation. Or as Maximus the Confessor puts it, the Resurrection is a new Big Bang; at Easter God inaugurates a second cosmos, a new origin of creation, in Jesus Christ.

Thus resurrection happens not simply to the crucified Jesus but to the whole timeline of Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim. This entire life, from Bethlehem to Calvary and every moment in between, is what God vindicates by raising it up from the grave.

Jesus saves.

Not the cross.

As the Epistle to the Ephesians announces, Christ’s faithful life, an obedience that did not yield in the face of death, is what recapitulates— re-sources— all things in himself, overcoming sin and thereby healing our afflicted nature. Maximus echoes Ephesians when he writes, “Jesus is neither mere man nor naked God, for the preeminent lover of humanity has become— unlike us— a truly human creature; so that, human creatures may now become portions of God.”

He does not mean merely to absolve us.

He means to make us equals.

And if his faithful life is the means by which he does so, then Mary’s work of delivering him to the world does not end at his nativity but continues until the moment he gives up his Spirit. Mary’s labor pains do not cease on Christmas Eve but they stretch forth across his lifetime, all the way up through noon and three on a Friday afternoon.

Jesus saves not the cross.

It is his faithful, obedient life even unto death that heals our nature.

And therefore—

His Mother shares his work by refusing to shout, “Do not crucify him!”

“I’m definitely partisan when it comes Jesus. And today…it sure sounded like you were using Jesus for your own project.”

I was standing in the narthex, my shame revealing itself in beads of sweat erupting across my forehead.

When Charlotte released her hands from my elbows, I confessed.

“You’re right,” I said, “I’m so embarrassed. I don’t know how I could be so blind. I don’t know how I could’ve done that.”

She shushed me.

She embraced me.

And she whispered into my ear.

“We all try to bend God so he suits us. Fortunately, like Mary with Jesus, God does not save us without us. If I hadn’t said anything to you, Jason, I’m certain God would’ve sent someone to set you straight.”

“Amen,” I whispered back.

Like everybody but his Mother, we are adept at twisting Jesus to our own ends. We make him a mere Absolver of sins. We turn him into a Teacher of wisdom. We shrink him to a Stalwart for social justice. We make him the object of spirituality, the face of nationalism, the promise of prosperity, the payment for trespasses, the transaction necessary for salvation.

But the LORD Jesus wants to make us equals, members of himself, portions of God.

He aims at nothing less than to be at-one with you.

All in all of you.

Just so—

He insists on getting in you.

Quite simply if surprisingly, Jesus dies upon the cross— and his Mother lets him— so that he might become our food and drink.

So come to the table.

Taste and see.

Eat and drink.

Feed on him by faith.

Like Mary at his cross, the labor is mutual.

Share this post