Genesis 30.1-24

In a 1995 essay entitled “Hermeneutics and the Life of the Church,” the American theologian Robert W. Jenson suggests that Christians evidence the inspiration and authority of scripture just to the extent we struggle to say what the text straightforwardly says.

That is, we avow scripture’s inspiration and obey scripture’s authority precisely by avoiding the privileging of parts we prefer and by wrestling with the parts we would prefer to avoid.

He writes,

“We all agree here, I suppose, that the Bible is somehow authoritative. But how does that work? For actual congregations of believers; I suggest, the matter is decided entirely by practice and very simply.

When we hear preaching in the broadest sense, that is to say, when the church's servants call us verbally to faith and obedience, do we observe the preacher struggling to say what the Bible says?

On more formal occasions, do we observe the preacher, or teacher struggling somehow to say what a specific text says? If we do, we then and there experience the authority of Scripture.

It is not a question of the preacher's or teacher's success in saying what Scripture says; the observable effort is by itself the necessary hermeneutical principle.”

Brothers and sisters, observe.

You’re about the see the authority of scripture in action. A sermon on this specific text— believe me, it’s a struggle. I don’t know what to say about what this scripture says; which is to say, I don’t know what to do with this tangled mess of people. Nor do I know what to say about the God who would have anything to do with them.

In the Book of Ruth, when Boaz prepares to marry Naomi’s stubborn, gentile daughter-in-law, the people of Bethlehem bless Boaz by saying, “May the LORD make the woman, who is coming into your house, like Rachel and Leah, who together built up the house of Israel.”

Even within the polite confines of a wedding toast, the people of God cannot avoid acknowledgement that the house of Israel is built upon a ramshackle foundation. The people of Bethlehem don’t say “May the LORD make Ruth, who is coming into your house, like Rachel, who built up the house of Israel.” Their benediction does not credit Rachel, the one whom Jacob loved (for a time) with constructing the house of Israel. It’s Rachel and Leah, the one whom Rachel’s impulsive lover wed on accident. “May the LORD make the woman, who is coming into your house, like Rachel and Leah, who together built up the house of Israel.” And, let’s be honest, even this mazel tov is too decorous a commendation.

It’s actually Rachel and Leah and Bilhah and Zilpah who lay the foundation for the house of the chosen people of God. And let’s not leave out Laban. After all, Jacob’s children are born on the estate of his petty, con-artist father-in-law, who just after this passage attempts once again to swindle his daughters’s husband.

The house of Israel is built on what reads like the transcript of an episode for the Jerry Springer Show.

When it first aired in 1991, TV Guide proclaimed the Jerry Springer Show “the worst TV show of all time.” But this episode in the Book of Genesis, it’s a chapter in the greatest story ever told. No, even more so this is a chapter in the narrative by which the Triune God identifies himself. There simply is no other God behind or beyond this seedy story.

Ladies and gentlemen, eyes up here. See the authority of scripture in action.

Watch me work. Look at me labor, likely in vain. I struggle to know what to say about what this scripture says. I don’t know what to do with these bitter, jealous, conniving people.

What kind of God would have anything to do with such people? We haven’t even gotten to the part of the story where the children of this five-some leave their little brother for dead to be sold into slavery in Egypt.

This passage has so many composite parts it’s easy to miss the movement of the plot. By Genesis 30, the once single, still exiled Jacob is married. He’s married to the beautiful Rachel, whom he loves. And he’s married to her sister, Leah, who, the Bible reports, has “nice eyes,” a Hebrew euphemism for “she’s got a nice personality.”

Jacob’s wedded life did not begin well and in Genesis 30 we learn— to the shock of no one at the wedding— that it is not going well. Genesis 29 concluded by telling us that that Jacob “loved Rachel more than Leah” and that “the Lord saw that Leah was hated.” If the cliche is true that a happy wife means for a happy life, then Jacob has two unhappy lives. Jacob may not have loved Leah, but evidently this did not prevent him from making love(?) to Leah. Jacob has four sons with Leah: Rueben, Simeon, Levi, and Judah. The first three sons all have names which are nothing more than passive aggressive puns expressing Leah’s acute unhappiness. Rueben, in Hebrew, means “Because the Lord has looked upon my affliction; maybe now my husband will love me” Simeon, in Hebrew, means “Because the Lord has heard that I am hated, he has given me this son also.” Levi— it doesn’t mean jeans— in Hebrew, it’s “Now this time my husband will be attached to me, because I have borne him three sons.” No child should have to bear such a burden.

Meanwhile, the romance that began with a stone-rolling meet-cute at a well does not weather well. Rachel’s barrenness fills her with envy for her sister, “Give me children,” she screams at Jacob, “or I shall die!” And Jacob responds with the calculated cruelty only a spouse can muster, “Whom am I, God? He’s the one who’s withheld from you the fruit of the womb.” Notice, Jacob doesn’t say us, “…withheld from us the fruit of the womb.” He’s made her all alone.

Rachel envies Leah her children. Leah envies Rachel her husband’s love. Consequently, both initiate a dysfunctional competition against the other. Each wife drafts her maidservant to outdo the rival spouse. Rachel recruits Bilhah to give her husband babies. Leah enlists Zilpah to add to her offspring. And evidently, amidst all this acrimony, Jacob has opted to boycott Leah’s bed; such that, Leah hires her husband for sex, trading Rachel an aphrodisiac fruit for the body of the husband who does not love her. “You must come in to me,” Leah says to Jacob, “for I have hired you with my son’s mandrakes.”

If you can keep up, by the end of the scripture text Rachel has contributed one child, Joseph, to the building up of the house of Israel. Leah gives birth to six sons and one daughter. Bilhah handmaids two sons. Zilpah offers another two boys. And in the very next verses, the children’s Grandpa, Laban, tries to steal all their grocery money through a grift having to do with the spottedness of sheep and goats.

These people—

This is the hot mess that is the foundation of the house of God’s chosen people.

“It is not a question of the preacher’s success in saying what Scripture says,” Jenson writes, “the observable effort is by itself the necessary hermeneutical principle.”

I wonder, have I labored long enough for scripture to exercise its authority over us?

I’ll work a bit harder.

Take my first church. Please, I wish someone had taken it from me.

A member of my congregation, Bill was a philandering, swindling contractor.

Against all good judgment and common sense, a couple in the congregation, Tim and Diane, had cracked open their nest egg and hired Bill to build a home overlooking the Delaware River. Their dream home became a nightmare when Bill took their money, used it pay off other debts and business endeavors, and then declared bankruptcy. I remember sitting in my sock feet in their half finished house listening to Diane rage as she unpacked decorative plates.

“Preacher, when you sit him down,” Diane had wagged her finger at me, “Make sure you go Old Testament on him.”

We all met in the church parlor. Tim and Diane, and Bill. And me. Tim and Diane sat in front of a dusty chalk board with half-erased prayer requests written on it. Bill sat in a rocking chair backed up against a wall, a criminally tacky painting of the Smiling Jesus hung in a frame right above his head.

I opened with what probably sounded to everyone like a condescending prayer.

No one said “Amen.”

Instead Tim and Diane exploded with unbridled anger and unleashed a torrent of expletives that could’ve peeled the varnish off the church parlor china cabinet. And Bill, who’d always been an unimaginative, sedate— even boring— church member, when backed into a corner, became intense and passionate. There was suddenly an urgency to him. With surprising creativity, Bill had an answer, a story, a reason for every possible charge.

In the middle of Bill’s self-serving squirming, Tim and Diane threw back their chairs and, jabbing her finger in his direction, Diane screamed at him, “You think you can just live your life banking on God’s forgiveness?!”

And then she pointed her finger at me instead and with a thunderous whisper said, “After all the good we’ve done for this church, we shouldn’t even need to be having this conversation!”

Then they stormed out of the church parlor. And they caused even more commotion when they left the church for good. Meanwhile Bill just sat there with a blank, guilt-less expression on his face and that offensively tacky picture of Jesus smiling right above him.

After an uncomfortable silence, I said to Bill, “Well, I guess you’re probably wondering if we’re going to make you leave the church?”

He squinted at me, like I’d just uttered a complete non sequitur, “No, why would I be wondering that?”

“Well, obviously, because of everything you’ve done. Lying and cheating and robbing your neighbors. It’s immoral.

And Bill nodded.

“The way I see it,” Bill said, “this church can’t afford to lose someone like me.”

“Can’t afford to lose someone like you? You’re bankrupt. You can’t even pay your own bills, Bill, much less help us pay our bills. What do you mean we can’t afford to lose someone like you?”

Bill nodded and leaned forward and started to gesture with his hands, like he was working out the details of another crooked business deal with great effort.

“You’re seminary educated right preacher?” he asked.

I nodded.

“And of course you know your Bible a lot better than me.”

And I feigned humility and nodded.

“I could be wrong,” he said, “but wouldn’t you say that the people Jesus had the biggest problem with were the scribes and the Pharisees?”

“Yeah,” I nodded, not liking where this was going.

“And back then weren’t they the professional clergy?” Bill asked. “You know...like you?”

“Uh-huh,” I grumbled.

“And, again you’ve been to seminary and all, but wouldn’t you say that across the whole Bible, the people God has a special heart for, the people God just loves to call and use, are people more or less like, well, people like me.”

“You slippery son of a...” I thought to myself.

“Sure, I know what I deserve,” Bill said, rocking in the rocking chair, “but that’s why you all can’t afford to lose me.”

I struggled to catch his meaning.

“I’m not sure I follow.”

“Well, without someone like me around church, good folks like you are liable to forget how it’s lucky for all of us that we don’t have to deal with a just God. Without someone like me around, good people like you might take it for granted how lucky it is that all we ever get is a gracious God who refuses to give us what we deserve.”

I can’t prove it, but I swear Jesus’ smile had grown bigger in that offensively tacky picture hanging above Bill on the wall. Maybe Jesus’s smile had gotten bigger because Bill was smiling. And I wasn’t.

I suppose it’s not just Jacob’s haram that’s a hot mess.

The Holy Bible is riddled with worse than unseemliness.

Evidently Noah packed more than animals two-by-two onto the ark because, after the flood, he passes out drunk and naked and then, to add injury to insult, he curses the grandkids who discover him. Two of the three patriarchs in the Book of Genesis pass off their wives as their sisters to lure the attention of other men. Abraham does it twice, and he even strikes it rich through the scheme. Along the way in the word of God, a son will sleep with the mother of his half-brothers. A daughter-in-law will dress as a prostitute in a ploy to seduce the father of her two dead husbands.

And in inverse proportion to the soap-opera sordidness of scripture there is not any hint of divine condemnation.

The Lord never so much as scolds Abraham for pretending Sarah is his sister. God doesn’t even should on Isaac for doing the same with his wife, Rebekah, “You probably shouldn’t do that, Issac.”

Consider the verbs Genesis credits to God in our text.

God gives.

God chastens.

God hears.

God gives (again).

God heeds.

God gives (again).

God endows.

God remembers.

God heeds (again).

God opens.

God removes (shame).

Not a single verb of reproach.

Each and every tawdry time, the God of Israel is like Jesus before the woman caught in adultery, saying “Neither do I condemn you.”

This is surprising.

After all, ever since the moment the church became predominantly a gentile church, we have been told again and again that the God of the New Testament is somehow different— greater in graciousness, more merciful— than the God of the Old Testament.

The God of the former is a loving promise-maker, we’re told on good authority, while the God of the latter is a vengeful law-layer.

“Preacher, when you sit him down, make sure you go Old Testament on him.”

“Have you actually read the thing?” I thought to myself.

If you look to the next chapter, to the resolution of Laban’s double cross of Jacob, you see that Genesis credits God with a verb that is even more direct. God speaks. The word of the Lord comes to Jacob and tells Jacob how to outfox his father-in-law.

God speaks. The word of the Lord comes to Jacob.

It’s critical we understand that locution.

If we do not, then Christians have neither the reason nor the right to read Israel’s Bible as also our scripture.

When the Old Testament tells us that “the word came to…” it does not mean that the Father sent some words to one prophet or patriarch and then sent another batch of words to another prophet or patriarch.

If that’s what it means, then, for Christians, the documents which comprise the Old Testament are nothing more than interesting historical background and cultural context for the New Testament.

Of course, this is all the Old Testament is for a great many— maybe most— Christians.

But this is not what “the word of the Lord came to…” means.

When the Old Testament tells us that the word of the Lord came to Jacob, when the Old Testament reports that the word of the Lord came to Isaiah son of Amoz, when the word of the Lord came to Elijah, saying ”Go and present yourself to Ahab, and I will send rain upon the land,” the word of the Lord in the Old Testament is the word incarnate.

The logos is Jesus.

The reason the word of the Lord responds, over and over again, to the hot mess that is the house of Israel, responds just like Christ before the woman caught in adultery, is that the word of the Lord in the Old Testament is Jesus.

Fully human, fully divine Jesus. Jesus did not become fully human and fully divine— that’s not the dogma. Jesus is fully human and fully divine, eternally so.

As Jesus says in the Gospel of John, “Before Abraham was, I am.”

The logos who speaks in the Old Testament is not some other extra word of God.

The logos is Jesus.

It’s Jesus, the Good Shepherd, who inspired David to pray, “The Lord is my shepherd…” The reason Isaiah prophesies that the messiah will be a Man of Sorrows is that the word who came to the prophet Isaiah was Jesus, the Man of Sorrows. This is why you cannot say that Jesus never said anything about how you should treat immigrants or practice chastity or any of the other subjects that are inconvenient in our secular age, for the word of the Lord that came to Moses on Mt. Sinai was Jesus.

To say, as the creeds and the apostles do, that Jesus is preexistent is to say that it is Jesus who is the voice that addresses his people in the Old Testament. And it’s no different for us today. When we preface the reading of scripture by saying, “Listen for the word of the Lord…” the creeds and the apostles would have us listen for the Lord Jesus, whether the scripture is from Matthew or Luke, Genesis or Judges.

If the word of the Lord in the Old Testament is not Jesus, then for us the Old Testament can only ever be the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible.

It cannot be scripture.

As Robert Jenson writes,

“It was a great maxim of all pre-modern interpretation that the very word who is incarnate as Christ was not first heard when he became flesh and dwelt among us. God speaks throughout the life of Israel and in her scriptures, and when he speaks this utterance is not another than that same word who is named Jesus.”

After their blowup with Bill, I found Tim and Diane waiting for me in the parking lot.

She poked me in the chest.

Hard.

And she hollered even harder, “YOU DIDN’T CONDEMN HIM AT ALL! I TOLD YOU TO GO OLD TESTAMENT ON THAT SOB!”

I bit my lip and mulled it over for a moment.

“I think I kinda, sorta did go Old Testament on him,” I said.

“We all agree here, I suppose, that the Bible is somehow authoritative. But how does that work?” Robert Jenson asks. Scripture’s authority works, he says, by watching a preacher or teacher struggle— and maybe fail— with an odd or inconvenient text.

Well, you may not be able to see from your seat in the pew, but I am sweating now and I have sweated. I’ve toiled and labored. And the upside of all my effort is that you can rest.

You can rest in the promise that God will deal graciously with you.

He will be Mercy to you when he finds you a hot mess.

After all, if Jesus is the word who addresses us in the Old Testament and if Jesus is what God says to us again in the New, then you and I are like characters in the last third of an Author’s unfinished play.

There is still more.

There is still more future, more time.

There is still these last days, the final bit of the third act.

And there is yet the finale.

But the Author has made choices in the first two acts.

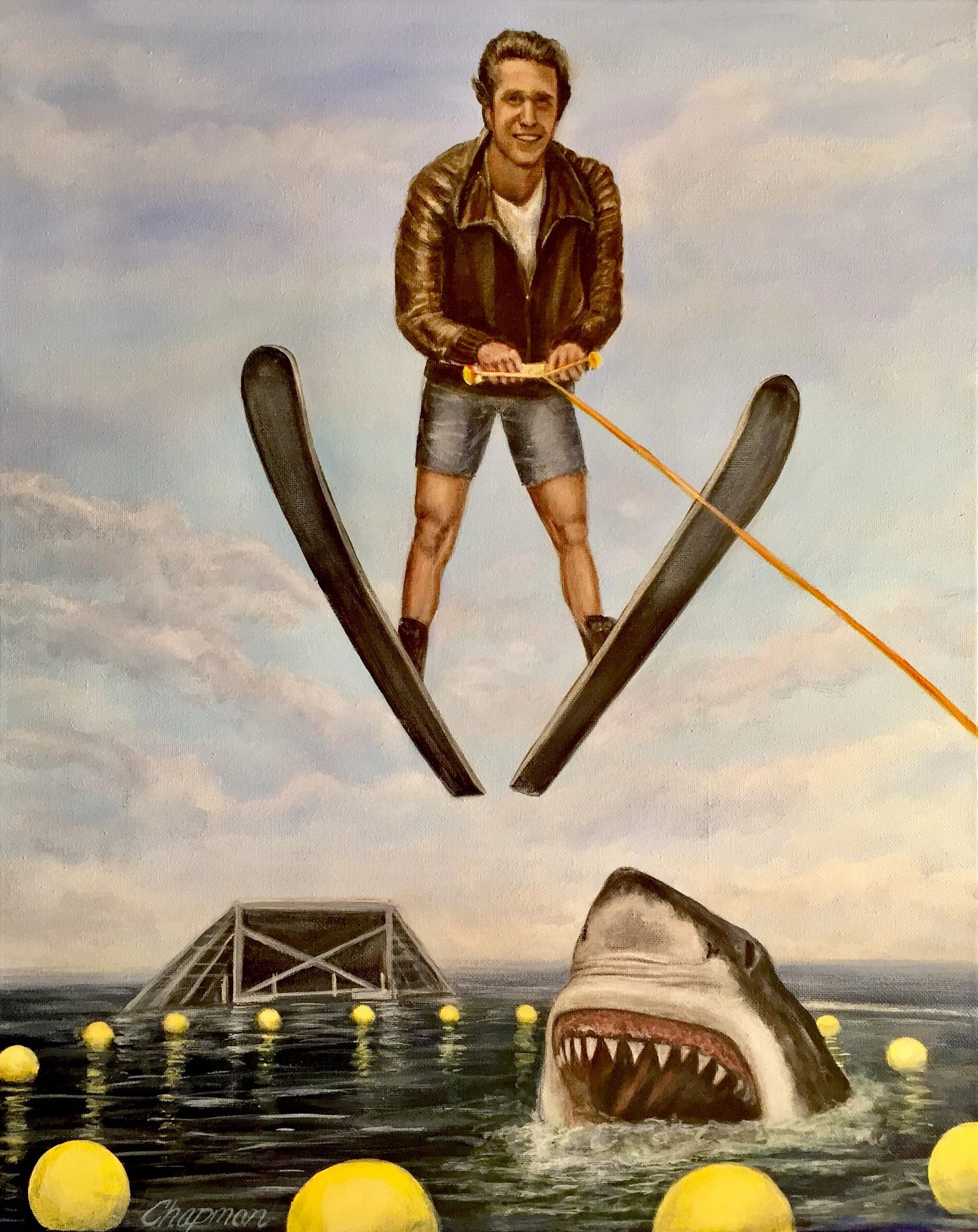

The Author has limited the options before him, and in doing so the Author has limited himself. He can still surprise us, sure. But the story we inhabit is not absurd. The story we inhabit has an Author with intentions; therefore, whatever the Author does next with us he’s not going to jump the shark. The balance of the story must be consistent with the words he’s already committed to the page.

Therefore, whatever is in store for you, you can rest in the knowledge that it will sound like, “Neither do I condemn you.”

Share this post