Justification is the Reverse of Predestination

Our righteousness is a matter of the same God who hardened Pharaoh’s heart

The lectionary passages assigned for the Second Sunday of Lent center on the Reformation’s linguistic rule for preachers who would speak gospel, otherwise known as the doctrine of justification by faith alone— apart from works.

Thus, in Romans 4 the apostle Paul recalls Genesis 22 to assert that faith in the message of Christ and him crucified, at which Peter recoils in Mark 8, is the only criterion by which God reckons us righteous before his judgment.

Typically, preachers interpret this rule for preachers to mean that the hearer’s response (belief) is the sole property according to which God will save them, which of course makes faith exactly what the Reformation sought to unseat— an anxiety-producing human work. For instance, if your faith supplies the righteousness a holy God requires for salvation, then how can you ever establish that your faith is sufficient? Did you venture forth at the altar call out of authentic faith? Or did you do so in a moment of ecstatic experience or under the duress of peer pressure? And if it was a genuine gesture of faith, then how does your present compare to it? Does it look more mountain or mustard seed?

While I insist that I belong to a tribe of Jesus’s friends whose doctrine is actually justification by works apart from faith, the Reformation’s rule has become, in the Christian cohorts who retain it, the very bondage from which Martin Luther worked to free troubled consciences. That this is so illustrates Robert Jenson’s caution about the church’s slogans:

“The problem with slogans is that as over time they become increasingly necessary, they just so tend to acquire live of their own, and then can become untethered from the complex of ideas and practices which they once evoked.”

It’s sadly ironic that so many should now construe the rule for gospel as a law.

After all, it should appear obvious that justification does not denote a human work of any kind given that the slogan renders its grammar in the passive voice: You are justified in Christ alone by grace alone through faith alone according to scripture alone. What the Reformers revolted to recover becomes clear when the rule’s speech is flipped from passive to active voice: God-in-Christ is— graciously, apart from works— making you righteous (because the gospel is a word in which Christ gives himself to you).

In other words, justification conveys just this surprising, perhaps unsettling, news:

You are not the protagonist of the Story you call You.

The doctrine of justification insists upon nothing other than the one-way love of God.

Justification implies not predestination so much as post-destination. Nothing exposes the weakness of justification as a word of law not gospel quite like the resistance it elicits once one points out how it seeks to center God as the active agent.

The Reformers intended to issue the claim in bracingly clear terms:

All things happen by God’s will.

This is merely a restatement of Martin Luther’s insight in the Bondage of the Will:

“For if you doubt…that God foreknows and wills all things, not contingently but necessarily and immutably, how will you be able…to rely on his promises?”

Luther goes on to conclude that our resistance to the doctrine of predestination is truly just a distrust of God.

Just so, our discomfort with justification’s correlative reveals our functional atheism.

The church’s slogan about our justification simply names that God wills in our act of gospeling just as God works in our response of faith— because faith is neither an attribute nor an accomplishment but a gift of God the Spirit. Hence, more so than we’d like countenance, the linguistic rule known as the doctrine of justification betrays essential connective tissue to texts like Exodus 9.12, in which Yahweh hardens the heart of the very Pharaoh to whom Yahweh has dispatched Moses to plead for mercy on behalf of God’s people.

Notice—

The doctrine which has centered the centrality of individual decision (for Christ) is actually a rule of speech that celebrates God as the active agent in all of the salvation story.

Surprisingly then, Romans 4 is no less a troublesome text for autonomous individuals than Exodus 9.

On the dialectic between the Lord’s agency and our own, Jenson writes:

God is said both to blind and deafen Israel and to send prophets in the hope that they may see and hear and repent. This is not mere incoherence. It is rather one manifestation of a logic that runs through all scripture.

The questions always come up, wherever the realities of God and faith are taken seriously. Putting them in the popular language about salvation: If salvation depends wholly on God, and if not everyone is saved, then if God does not choose to save me, what is the use of my faith or works? Or if I am responsible to open my own eyes, how can I fully rely on God as my Savior, since I may at any moment undo everything by failing that responsibility?

What we must come to understand is that neither question is appropriate, for the simultaneity of “God decides and works all things” and “see, hear, and be saved” is itself the truth about our situation with God.

Believers are bound to “work out [their] own salvation,” precisely because “it is God who is at work” in them (Phil. 2:12–13). Both propositions can be true, and true only together, because between God’s will and a creature’s will there is no “zero-sum game.”

When you and I must decide some matter, to the extent that you choose I do not, and to the extent that I choose you do not. Thus we are always negotiating, for we are both finite creatures with a limited scope for choice. But it does not work that way when God decides to open my eyes and I must, in response to his simultaneous appeal, myself decide to open my eyes. High medieval Scholasticism’s statement of the relation between God’s choice and ours is so simple and so patently right that it is very hard to grasp: God’s will is impeded by nothing; therefore if he chooses that I shall do x, I will do it; and if he chooses that I shall do x of my own free will, that is how I will do it.”

In this way, the doctrine of justification is no more than a riff on the doctrine of creation ex nihilo. That is, God does not act upon his creatures in the same way his creatures act upon each other; in fact, he does not act upon them at all. What God does is speak creatures into being ex nihilo, continuously and eternally.

The Creator both hardens Pharoah’s heart.

Whilst Pharoah freely hardens his heart.

Both statements must be true if the creatio ex nihilo is true.

Just so—

Our justification is a matter of the same God who hardened Pharaoh’s heart.

The Creator gifts us faith through the gospel.

Simultaneously, through the Lord, we freely open our hearts to the gospel’s content, Mary’s boy who lives with death behind him.

Ironically, such an uncompromising emphasis on God’s active agency throws us back onto what the slogan originally intended to secure, trust in God alone.

This is not about an abstract deity “picking” from outside of time. Rather, it describes the God whose reality and will are disclosed only in the event of speaking the gospel, who is the absoluteness and unconditionality of the gospel. The absoluteness of the gospel, Jenson writes, is the absoluteness of that very word the hearing of which, and only the hearing of which, is the event of our freedom before God.

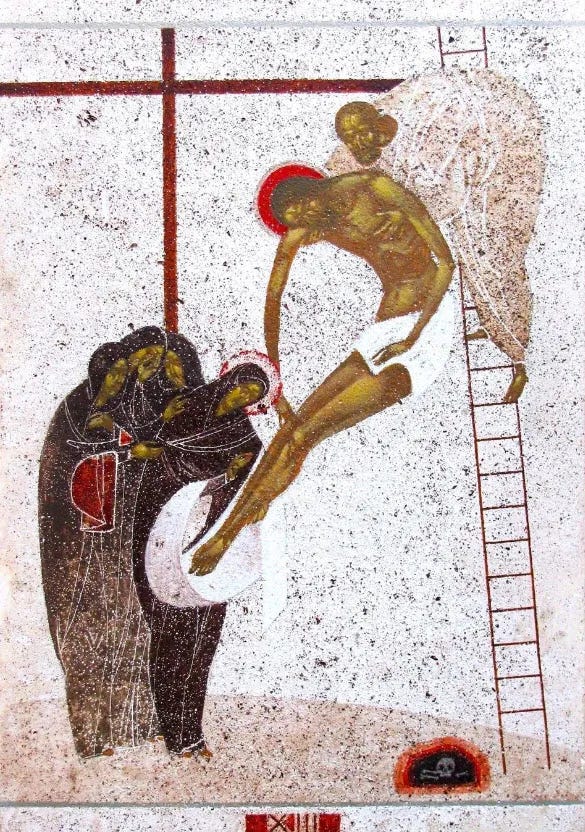

(art by Lyuba Yatskiv)

Might a loss of a sense of the efficacy of the sacraments contribute to the anxiety that you aptly named within Protestant circles regarding salvation? The existence of a tangible source of salvation from God does remove some of the onus from the individual to have their faith completely in order. A strong belief in the efficacy of baptism and the Lord’s supper reinforces the reality that faiths and salvation are both from God.

Jason, Grace and peace to you and to your family! Is the extensive quote that you have from Jenson in his "Slogan" book or somewhere else? I'd like to do some reading!