Grace UMC — Acts 1.1-11

One of my friends, a member of my former church, spends half his year in Florida. He coaches cross-country at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. He was on a group text thread with his runners as the coaches and runners messaged each other pleas for help and advice for where to flee as they attempted to escape the school shooting in 2018. He messaged me that night to give me the names of his kids who were still in surgery, and the name of the murdered bus driver who drove the team to all their meets. He asked me to add them to the church prayer list.

“Pray for Maddie,” he messaged me, “She has a collapsed lung. She was shot in the arm and the leg and the back. Her ribs are shattered. I’m not in denial or shock. I’m not depressed. I’m just angry. I’m just really, really angry. The SOB pulled the fire alarm so he could shoot the teachers and the children as they exited. And I’m angry at the thought that the Church has nothing else to say except we’re called to forgive Nikolas Cruz for what he did. Those who would forgive apart from all his evil deeds and America’s sinful indifference being put to rights have substituted themselves for God. Whatever happened to judgment? If Christianity is nothing more than an apparatus of absolution and forgiveness, then it’s positively immoral. If that’s blasphemy so be it.”

It’s not blasphemy.

And he was not wrong.

If the name of your church, Grace, is all there is to the Gospel, if forgiveness is all there is to Christianity— forgiveness without judgment, absolution apart any justice, love without any reckoning with sin— then Christianity is immoral.

The New Testament scholar Reginald Fuller registers the very same point in his book Interpreting the Miracles.

“Forgiveness,” Fuller insists, “is too weak a word for what God does.”

Forgiveness is too weak a word for what God does.

Grace doesn’t go far enough to describe the purposes of God.

The day after the Parkland massacre he messaged me again:

“Thoughts and Prayers?! WTF?! What’s even more galling is that as the nation grieved last night, just hours after the massacre, the NRA contracted the same operatives who circulated conspiracy theories about Sandy Hook and committed funds to an attempt to spread allegations that the Parkland student protesters— my kids— were child actors. I gotta tell you Jason, when the majority of American Christians believe that two people of the same sex kissing each other is a bigger problem than gun violence, I really can’t identify as being a Christian anymore.”

And…he doesn’t.

Grace didn’t go far enough for him in order for the Gospel to sound like good news.

Like Jesus today disappearing behind the clouds, Bob left.

But if forgiveness is too weak a word for what God does, what is the better word?

Ask the average American churchgoer to describe God and he or she will almost certainly first describe God as “loving.”

This is not wrong.

It’s thin.

American Christians also commonly characterize God as compassionate, merciful, welcoming, accepting, and— of course— inclusive. Very few Americans however— very few white Americans— will think to respond to such a question by describing God as just. This is both odd and unfortunate because the revelation of God as a God of justice is such a recurring theme in the Old Testament that we should regard it as the keystone of Israel’s faith and thus at the center of the mind of Christ. Anyone who prays the psalms for any length of time will note their relentless lament that without judgment, without justice, nothing can else flourish.

The centrality of God’s justice is to be found as early in the scriptures as the Book of Genesis where Abraham appeals to the Lord, “Shall not the Judge of all the earth do right?” If there’s a single, overriding message of the Old Testament prophets, a message we believe Jesus makes flesh and carries in him to the cross and today takes with him to the right hand of God the Father— if there’s a single, unrelenting refrain in scripture it is, “Something is wrong and must be put right.”

Indeed, from Genesis 1 to Revelation 21, the holy scriptures bear witness that the predicament of fallen humanity is so serious, so grave, so irredeemable that nothing short of divine intervention can rectify it.

Rectification— that’s the better word.

It’s the word the Lord proclaims to the prophets, like when the Lord declares through Isaiah to those held in bondage, “Hearken unto me, O house of Jacob, I bring near my righteousness; it shall not be far off, it shall not tarry.”

I bring near my righteousness; it shall not be far off.

The Apostle Paul takes up this loaded Old Testament word, righteousness, when he announces that in the coming of Jesus Christ the righteousness of God is being unfurled. Whenever we reduce the Gospel to a cliche like “God is love” or to a cliff note like “Christianity is about forgiveness, “ it’s the righteousness of God that is missing.

God is Love. The Gospel is about grace. Christianity is about forgiveness.

But love and grace and forgiveness are too weak of words for what the God of the Bible purposes to do.

For Paul and the prophets, absolutely central to their message is the righteousness of God. Nevertheless, the English word righteousness is so antiquated and religious, it’s easy for us to miss entirely the radical scope of the biblical message.

Pay attention— Drew assured me you all were sharp enough to keep up; Milton wasn’t so sure.

The words translated variously in your Bibles as righteousness and justice and judgment and justification and deliverance and rectification— in Hebrew and in Greek, they are all the same word. Dikaiosoune in Greek.CTzedek in Hebrew. Now, righteousness is a noun in English, but in both biblical languages it functions as a verb.

Righteousness is not simply an attribute of God. Righteousness is the activity of God. Righteousness is more than who God is. Righteousness is what God does. And it’s meaning in the Bible is manifold.

God’s judgment is God’s justice, and God’s justice is God’s righteousness and God’s righteousness is God’s justification— it’s all God’s rectification; it’s all God’s work of putting God’s world to rights.

Last month, as part of a pilgrimage to Israel, I toured the tunnels only recently excavated beneath the Western Wall of what remains of the Temple in Jerusalem. Far below the Wailing Wall, where believers pray aloud and stick notes to God in between the stones, archeologists have uncovered intricate drainage systems, elaborate mikvahs, and even a Roman theater. It’s a massive and impressive structure— some of the stones in the Temple wall weigh more than two Airbus 320 planes put together; nonetheless, when the Second Temple was unveiled and the ribbon cutting commenced those who could remember the first Temple did not join in the celebration.

They wept.

Standing in the shadows under the Wailing Wall, our tour guide asked us what sounded like a simple Sunday School question, “Why did they weep when they saw the new Temple? Why did the Second Temple not compare to Solomon’s Temple?”

Being an Enneagram 8, I started to raise my hand in the dark, but he didn’t wait for an answer.

“The new Temple wasn’t as good as the old Temple,” he explained, “because the Jews who returned home from exile were poor and uneducated— the C students. They didn’t have the smarts or the shekels to restore the Temple to its former glory. Meanwhile, all the educated and elite Jews made peace with their situation and remained in exile. They gave up on their God and they gave in to their enemy. They accepted the scourge that afflicted them and settled for this world, the world the way as it is, as the only possible world and thus they made their home in Babylon.”

“Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up at heaven?”

Every year the Great Fifty Days of Easter ends with Jesus, who was high and lifted up on a cross for the forgiveness of your sins and raised up from the dead for your justification, taken up to sit at the right hand of the Father. Every Easter season ends with the Ascension. Every Easter ends with angels asking us, “Why do you stand looking up to heaven?”

Why?

We look for the Kingdom of Heaven because we live in this world.

How could we not look for the Kingdom of Heaven?

This world is not yet what God declared of it at the beginning.

Things are not as they should be nor are they yet what God has promised they will one day be.

Though we often forget it, as they did again this Tuesday, the Powers of Sin and Death have a habit of rudely reminding us: this world is not yet once again “very good.”

Nor are you.

Nor am I.

So the answer to the angel’s question is an easy one.

Why do we stand looking up at heaven?

Because— bigger than grace, more than forgiveness— the promise of the Gospel is that a better world is on the way.

A better world is on the way.

With this picture in the Book of Acts of Jesus high and lifted up beyond the clouds, St. Luke shows you what Paul and the prophets tell you with that word, rectification. The good news of the Ascension is not that Jesus was raised to sit at the right hand of the Father. The good news of the Ascension is that one day, from the right hand of the Father, Jesus will return to this world, bringing heaven with him, and all that is broken will be mended. From the Father’s right hand, Christ will come again and make all things new.

God forbid that we ever get so comfortable with this world. God forbid that we ever grow so comfortably numb to this world and its cut-and-paste tragedy that we stop looking up to heaven.

This is what the theologian Karl Barth meant when he wrote, “What other time or season can or will the Church ever have but that of Advent.”

Whether the calendar say it’s Easter or Ascension or just an ordinary Tuesday, no matter what the headlines say, no matter how good you feel about the face in your mirror, every day is Advent.

Every day is a life of waiting in this world for the better world that Christ Jesus our Lord promises will come.

Every day is Advent. Every day we’re waiting for the return of the King. Waiting for him to put the world to rights. Waiting for him to rectify all that is wrong and, seemingly, irredeemable.

Rectification— not just forgiveness, more than simply love, bigger than grace.

Rectification— that is the word for what God purposes.

Rectification— that is the far reach of God’s Gospel promise.

Rectification— one day all who’ve been lost will be raised up and mended, mourning and crying and pain and DEATH will be no more.

And every wrong will be put to rights.

Rectification— that’s the word that should keep Wayne LaPierre awake at night; that’s the only word that is good enough to be heard as good news in a place like Uvalde.

Today is Ascension Sunday, sure, but every day is Advent.

In the meantime, do we just wait?

Do we do no more than stand still, looking up at heaven?

On my way home from the Holy Land last month, I read a story in the New York Times about Andriy Zelinskyy, a Jesuit priest who serves as the coordinator of military chaplains for the Ukrainian Catholic Church.

Having just returned from the front, Father Zelinskyy explained his role as a representative of the Church amidst so much violence and injustice:

“We priests must help the soldiers choose good, seek truth, contemplate beauty, and pursue justice not only because these are all essential to preserving their true humanity but because goodness, truth, beauty, and justice describe the world that is to come. The Kingdom Christ promises that he will bring when he returns. In a sense then, I see my role as helping lean the Kingdom of Heaven towards the soldiers.”

You may not wear a collar like Father Zelinskyy or a stole like Pastor Drew, but for all of you who have been born of water and the Spirit, your vocation is not appreciably different.

The baptismal font is a time machine, a summons to live as though you’re from the future, tipping tomorrow out onto today.

And it’s not the tall, impossible task it might sound.

Notice—

Father Zelinskyy never set out to land himself in the pages of the New York Times. He never determined to be a hero or a saint. He’s not doing anything different today than he was doing ten years ago when he first became a priest and a chaplain. When the extraordinary moment met him, it discovered him doing the same ordinary work of the Church he had been doing before:

Hearing confessions and absolving trespasses.

Proclaiming the promise of the Gospel.

Offering Christ in bread and wine.

Clothing sinners with Christ’s own righteousness by water and the Spirit.

Leaning the Kingdom of Heaven towards this world.

My friend—

He may have left Christianity Inc, storming off in a cloud of righteous anger. But he’s never stopped submitting prayer requests. “Pray for Alyssa,” he messaged me this week.

“She was one of my runners. She’s an advocate now, eloquent and impassioned, but she’s still got wounds that can’t be seen and will never be healed. I’m sure those wounds are aching right now. I’m still angry and I’m not coming back to Christianity, I will ask you to pray. I don’t have any choice. If there’s a better world on the way, it’s clearly not going to be one that we build. It can only be one that is brought to us— one we absolutely do not deserve.”

He left.

But he still wants the Church to pray.

The challenge of faith in this time of Advent is not to discern what we ought to do to respond to extraordinary, difficult moments.

The challenge of faith in this world is to trust that when the moments meet us we’ve already been given the work we must do.

As the angels say at the Ascension, “Why bother looking up to heaven?

When the Kingdom finally does come, it’s going to come in the same unimpressive way it did before— it’s not going to look any different than the life he’s already shown you.

In other words, it’s not on us to make the world a better place. That’s an impossible task. We can’t do what only God can do. We’re not called to make the world a better place. Rather, in this time of Advent, we’re called to be the better place God has already made in the world.

So fear not.

Because we’re never not in the time of Advent, our task today is the same as our task yesterday and it will be here for us tomorrow too. At your church and mine.

As your own pastor put it after the mass shooting in Las Vegas:

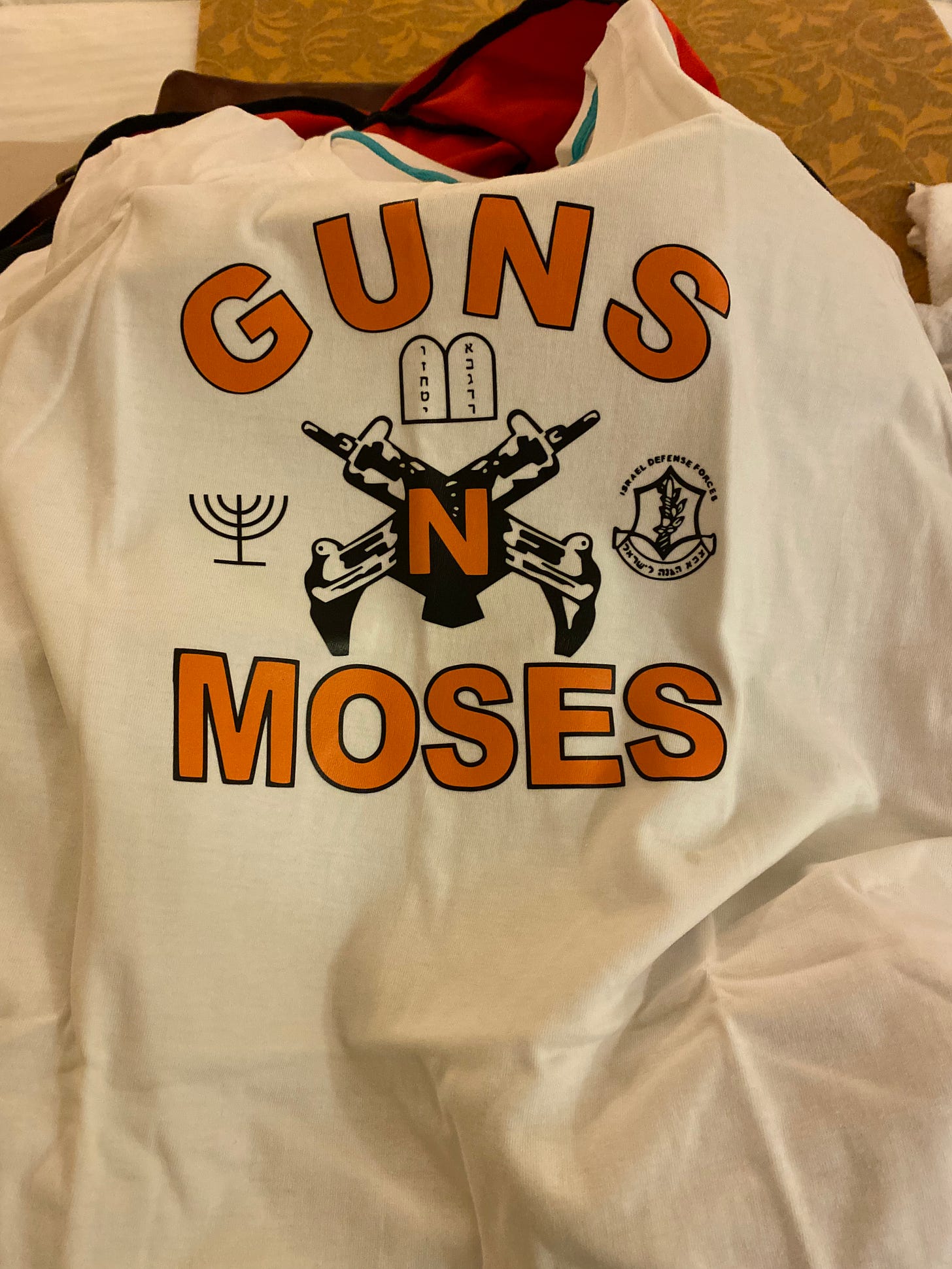

“It’s the task of the Church to be the reason someone— not everyone, someone— no longer owns guns.

It’s the task of the Church to be the reason someone— again not everyone, just someone— is no longer a member of the KKK.

It’s the task of the Church to be the reason someone has a friend outside their race.

It’s the task of the Church to be the reason someone who voted Democratic invited a Trump supporter to coffee.

It’s the task of the Church to be the reason a real estate developer built affordable housing in the same neighborhood they themselves would be willing to live, why someone has a roof over their head when their family kicked them out of the house, why a child of abuse is not destined to become abusive, why someone was forgiven, and not cancelled, why someone was imprisoned, and not killed, why, in the moment just before someone died from a gunshot wound, they were unafraid.

As the world once again works its liturgy of Death, let us abide the liturgy that’s been gifted and tasked to us: the liturgy of Life and Life Everlasting.”

In this ongoing Advent, our task is simply to be the Church, to tip tomorrow out onto today, to lean the Kingdom of Heaven out onto this world with far too much Hell in it.

Our task is to be the Church until our ascended King comes back in final victory.

Share this post