The lectionary Gospel for this coming Sunday of Epiphany is John 1:43-5:

The next day Jesus decided to go to Galilee. He found Philip and said to him, "Follow me." Now Philip was from Bethsaida, the city of Andrew and Peter. Philip found Nathanael and said to him, "We have found him about whom Moses in the law and also the prophets wrote, Jesus son of Joseph from Nazareth." Nathanael said to him, "Can anything good come out of Nazareth?" Philip said to him, "Come and see." When Jesus saw Nathanael coming toward him, he said of him, "Here is truly an Israelite in whom there is no deceit!" Nathanael asked him, "Where did you get to know me?" Jesus answered, "I saw you under the fig tree before Philip called you." Nathanael replied, "Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!" Jesus answered, "Do you believe because I told you that I saw you under the fig tree? You will see greater things than these." And he said to him, "Very truly, I tell you, you will see heaven opened and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of Man."

People often send me their questions about faith, doubt, God, and the Bible.

A recent such question was posed so:

“Jason, there are a lot of questions I could submit to you, but in my opinion, given what science teaches us about the world’s origins, all those questions boil down to the biggest question of all.

Is there a God?”

When I started out as a pastor twenty plus years ago, it was vogue to reconstruct catechesis under the slogan “Living the Questions.” Of course, the gospel can never be said the same way twice; therefore, it’s appropriate to present the message of Jesus’s death and resurrection according to the idioms of our time and place. Nevertheless, it was the case then as much as it is now: you don’t need any encouragement to question the faith.

Many beleaguered believers never venture beyond deconstructing their former faith. Indeed, ours is a cynical culture, one that conditions us to question and doubt received tradition and the institutions that steward it, including the Church and her gospel.

Now I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with questioning; I’m not suggesting there’s anything wrong with doubt.

After all, by definition the very concept of faith requires doubt.

You can only have faith in what is not certain.

For example, I have faith that my children will always love me, but that my children will always love me can never be a certainty. And if something is not certain then it is not immune to doubt. There’s nothing wrong with questioning.

Jesus in the middle of Sunday’s lectionary Gospel passage chastises Nathaniel for believing too quickly, too blindly:

Nathanael replied, "Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!" Jesus answered, "Do you believe because I told you that I saw you under the fig tree? You will see greater things than these."

The problem is that I don’t know many people who are like the Nathaniel, believing quickly and without question.

Instead I know a lot more people who are like the pre-Christian Nathaniel at the beginning of the Gospel story—

The Nathaniel who rolls his eyes dismissively at the notion that any wisdom could ever come from a backward, ignorant, archaic place like Nazareth.

I know a lot more people who are like that Nathaniel, who think all religion is, in a sense, “from Nazareth.”

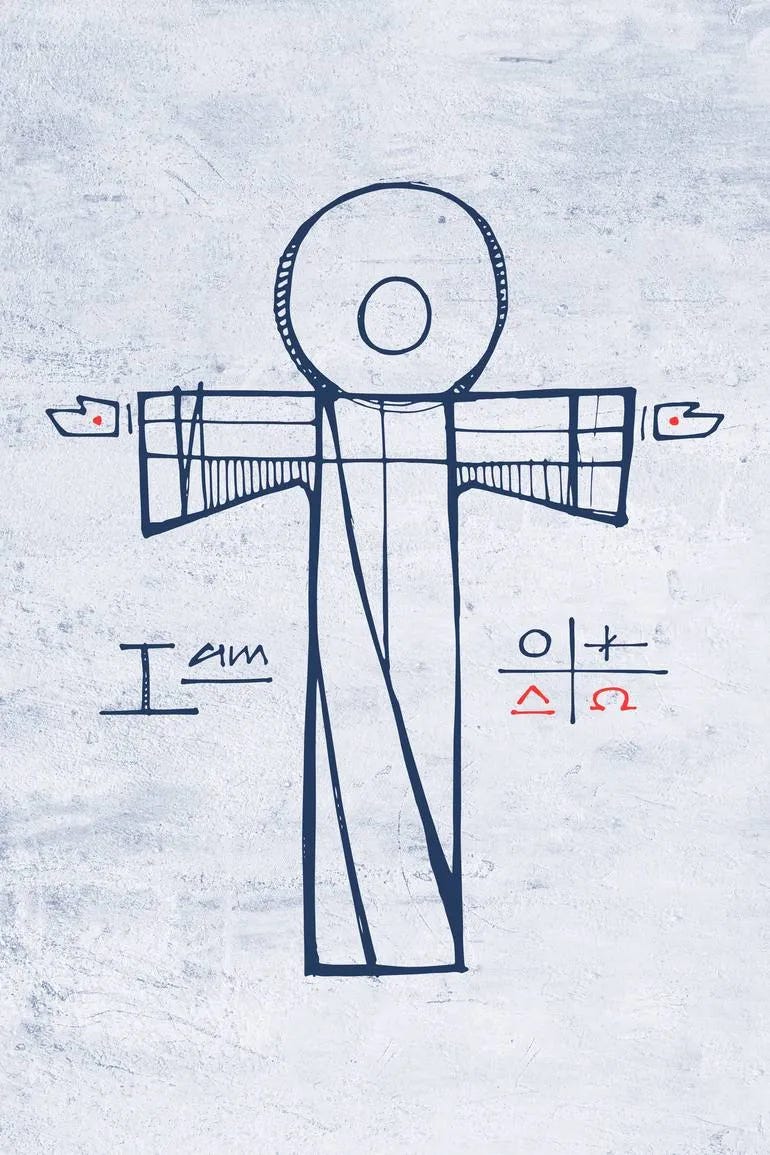

If you think you have to choose between intellectual honesty and belief in God, then you’ve simply not understood what Christians mean by the word God.

If you think empirical science could ever disprove God, then you’ve only proven that you forgot to investigate the ancient meaning of the word God. If you think the biggest question boils down to “Is there a God?” then you don’t realize what Christians— and Jews and Muslims and Hindus and even some Buddhists— mean when we say the word God.

So in light of the lectionary Gospel for this Sunday of Epiphany, I don’t want to encourage you to question your faith.

Or rather, instead, I want to encourage you to question your faith in the assumptions the modern world has given you:

The assumption that the 21st century raises questions to which the ancient faith has no answers.

The assumption that Christianity is not as intellectually rigorous as any other discipline.

The assumption that we as modern people know a great many things the ancient Christians did not know— and that may be true, but it’s also true that the ancient Christians knew a few things very well that very few of you know at all.

Namely, philosophy and logic.

I don’t want to encourage you to question God.

Instead I want to make an argument, for God.

I want to make a philosophic argument, one that comes out of the ancient Christian tradition, from Thomas Aquinas, who was probably the greatest thinker in the history of the Church. I want to take you through Thomas’s argument because if you understand his logic then you will understand what Christians mean, fundamentally, by the word God.

If you understand the word God, then you will understand why “Is there a God?” is not, in fact, the biggest question.

Rather, God is the answer to the biggest, most obvious question of all.

Now first, Thomas would say that not only is the question “Is there a God?” not the biggest question of all; it’s not even a good question. It’s a bad question. Why?

It’s a bad question because its premise is wrong.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tamed Cynic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.