"Not in His Wrongness"

In a sermon that is truly theological, no side is affirmed uncritically.

To be blunt, but I sometimes wonder if an ailment afflicting Christ’s body is that too many of her public proclaimers appear not to like their hearers.

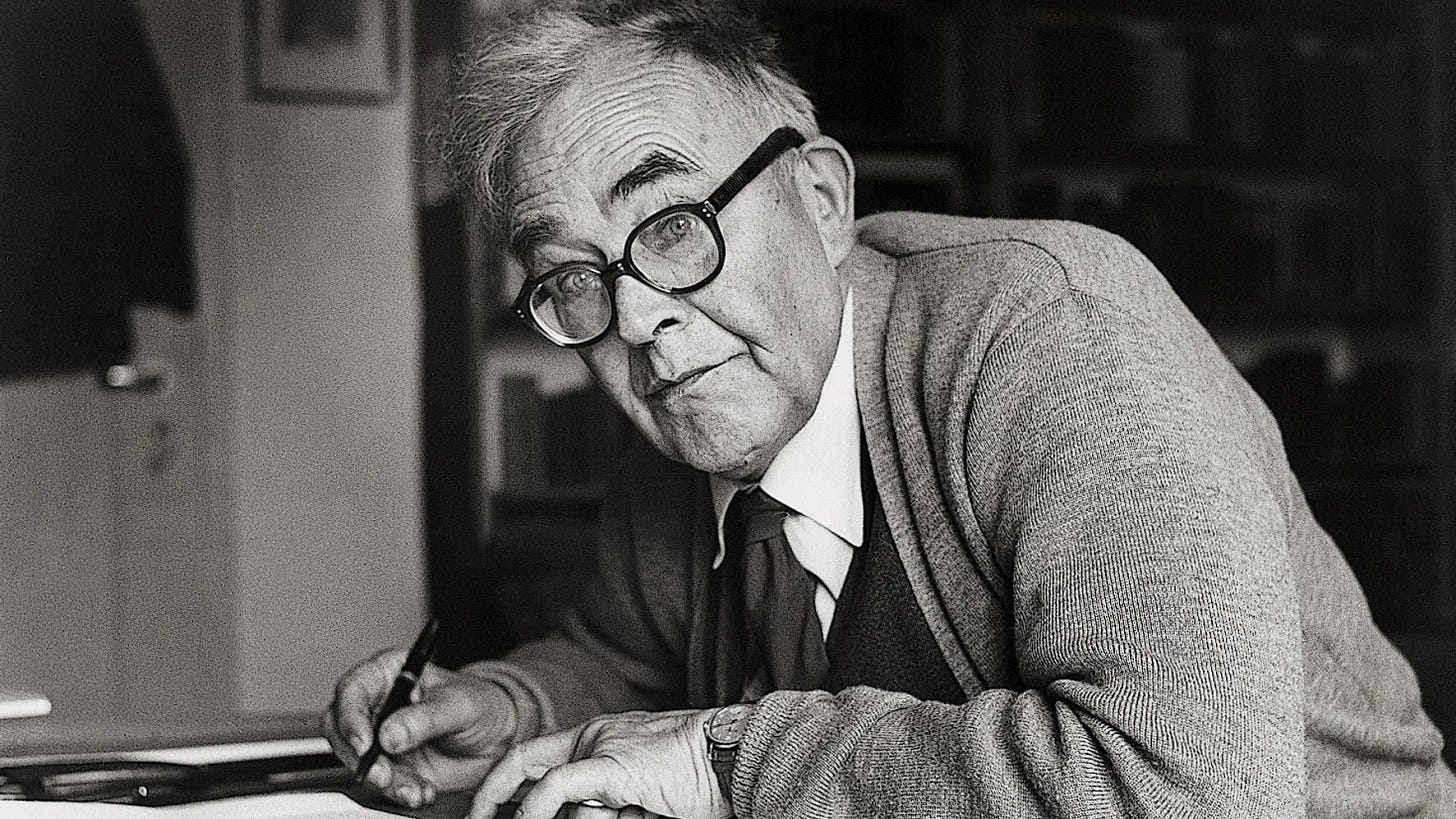

At some point during the inaugural year of the Iowa Preachers Project, I commended Angela Dienhart Hancock’s wonderful book Karl Barth’s Em…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tamed Cynic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.