Romans 1.13-17

When I was a student at the University of Virginia, I befriended the retired theologian Juliann Hartt. One afternoon over glasses of sherry, I confessed to Dr. Hartt a particular sin that burdened me. Because I was a relatively new Christian, Dr. Hartt gospeled me on the sly.

He told me a story.

Taking a few sips of sherry, Dr. Hartt in his North Dakota accent said, “My father, as you know, was a prairie pastor. Well, he had a friend, a colleague I suppose you could say, a Norwegian Lutheran pastor named Johan Aasgaard. One time, at some conference or another, Dr. Aasgaard told my father about a woman who was in his congregation.”

Dr. Hartt took a sip from his short, little glass:

“Dr. Aasgaard had performed this woman’s wedding just a few months earlier. She came to see Dr. Aasgaard one afternoon not long after the wedding.‘Dr. Aasgaard, I have to talk with you,’ she said, shaking and trembling and crying, ‘I must talk to you now.’ So he knew she’d come to confess something to him. And he said to her, ‘There’s a liturgy in the hymnal for someone in your situation.’

He opened the book up to Luther’s service of confession and absolution, and he invited her to kneel there in his office just as he knelt in front of her. “They began working their way through the ritual, and she confessed to her preacher. She told him that before she had been married or even met her husband, she’d had a relationship with a doctor. She’d become pregnant by the doctor, and the doctor, who wanted nothing to do with a child, pressured her and pressured her and pressured her into having an abortion.”

Dr. Hartt stopped and looked at me to make sure I understood.

“Bear in mind, this was in the 1920s. She relented under his pressure and the doctor arranged for a colleague to do it and she had the abortion. “‘That was the end of the relationship with the doctor,’ she confessed to Dr. Aasgaard, crying.”

And Dr. Hartt continued the story:

“When her husband started courting her, she felt like she should tell him what she had done, but she couldn’t bring herself to tell him. And when the relationship became serious, she felt like she should tell him what she had done, but she couldn’t bring herself to tell him. And when he proposed to her, she felt like she should tell him what she had done, but still she couldn’t tell him. And when they got married, every day she felt like she should tell him what she had done, but she could never bear to do it. “‘Now,’ she said to her preacher, ‘every time he touches me all I can think about is what I’ve done and how I’ve betrayed him. And whenever he talks to me, all I can think about is what I’m keeping myself from telling him.’

“When she finished confessing her story,” Dr. Hartt told me, “this pastor stood up and placed his hand on her forehead and said to her, ‘In the name of Jesus Christ and by his authority alone, I declare unto you the entire forgiveness of all your sins.’ “‘She wept for a long while,’ he told my father,” Dr. Hartt said, “and then she stood up, wiped her eyes dry, and straightened herself up and said, ‘Well now, I guess I better go home now and tell my husband this story.’ “And Dr. Aasgaard looked her straight in the eyes and said, ‘What story?’”

What story?

Of course, the preacher Aasgaard lied— there was no wonderful exchange between the woman's sin and Christ Jesus’s righteousness— if it is not true that the gospel “is the power of God for salvation to everyone who has faith, to the religious first and also to the irreligious.” Likewise, if the gospel is not the power by which God creates— by speech, by promise— a perfectly right relationship with him, then the sin— my sin— for which Dr. Hartt first told me that story remains on my rap sheet. And I am dead in my trespass.

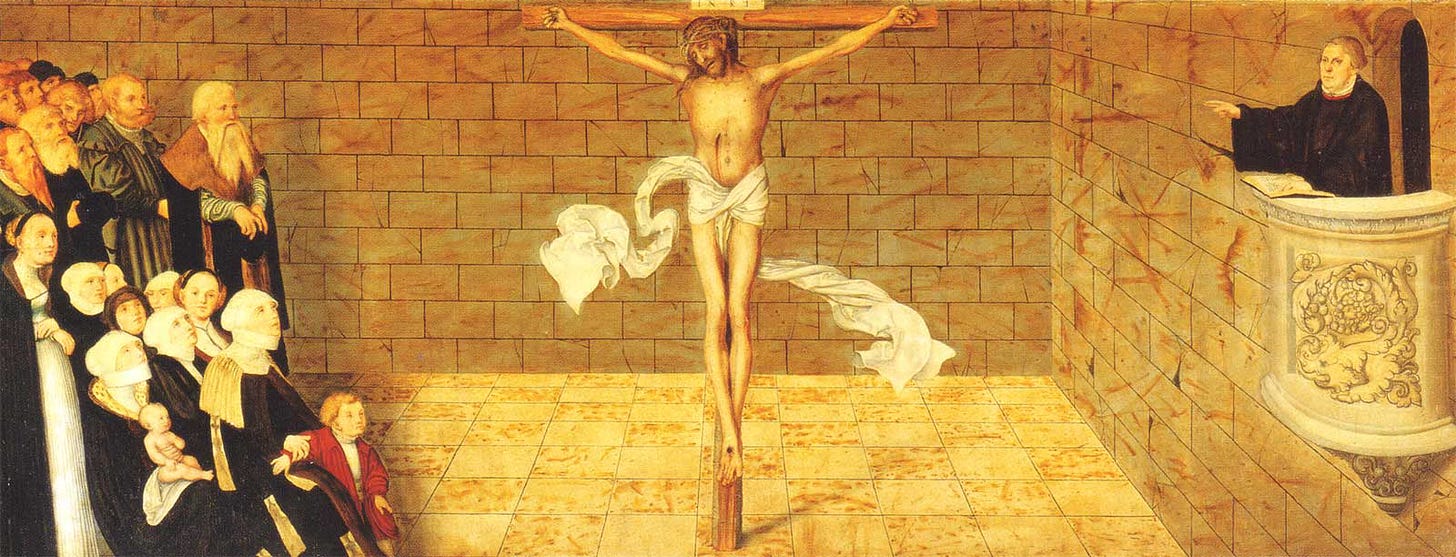

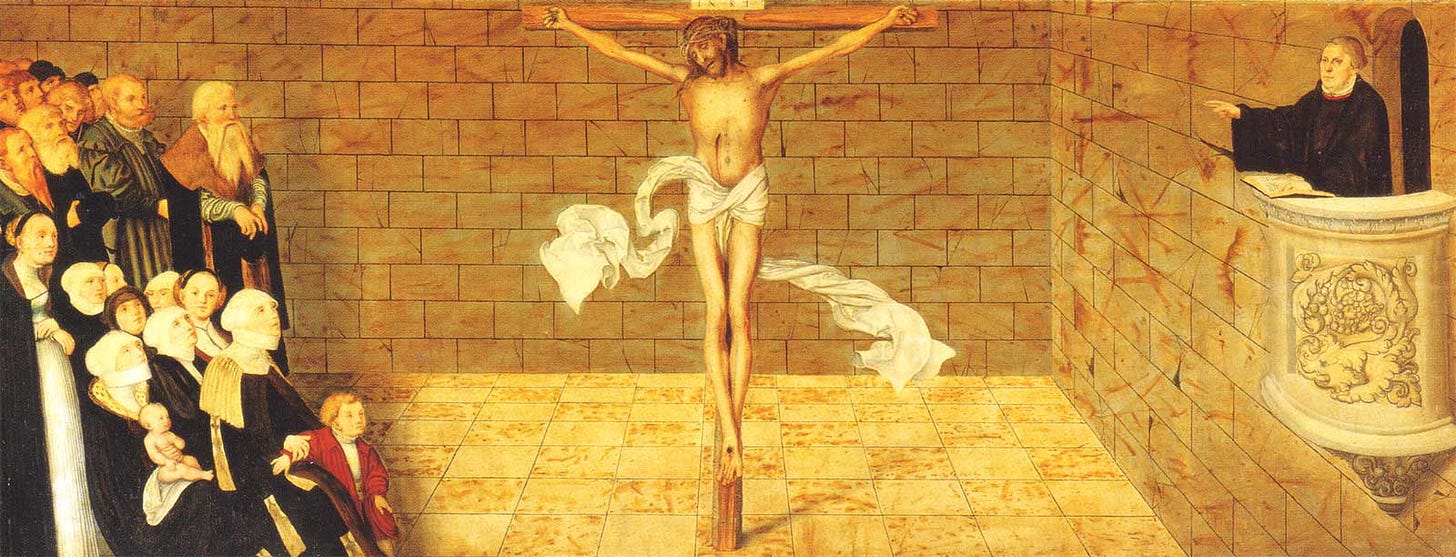

A little over five hundred years ago, Martin Luther, the founder of the Protestant movement, was a biblical scholar at the University of Wittenberg and an Augustinian monk. He wrote textbooks on the scriptures. He lectured on the scriptures. He prayed the scriptures several times a day.

And he hated God.

Or rather, he hated the God given to him by a church that had lost the gospel.

Late in his life, looking back on his discovery of and conversion to that gospel, Luther credited Paul’s thesis statement in the Epistle to the Romans.

Luther writes:

“I greatly longed to understand Paul’s Epistle to the Romans but nothing stood in the way but that one expression, “the righteousness of God,” because I took it to mean that justice whereby God is just and deals justly in punishing the unjust. My situation was that, although an impeccable monk, I stood every day before God as a sinner troubled in conscience, and I had no confidence that my merit would assuage him. Therefore I hated God and murmured against him. Night and day I pondered until I grasped that through gift and sheer mercy God justifies us through faith. Thereupon I felt myself to be reborn and to have gone through open doors into paradise. When I discovered the distinction that the law is one thing and the gospel is another, I broke through.”

The power of God’s gospel as the Spirit led Paul to proclaim it to the church at Rome ignited the Reformation.

By speaking promises, God justifies you.

By trusting those promises, God gifts you a right relationship with him.

Period— no asterisk, no fine print, no reciprocity required.

Again and again, Paul’s Epistle to the Romans has roused the church to passion and freedom.

Two centuries after Luther, John Wesley, the founder of a renewal movement in the Anglican Church, experienced a similar discovery of the power of God’s gospel. The son of a priest, John Wesley was already ordained in the Church of England. He had sailed the Atlantic as a missionary. He had earned a reputation for works of mercy to the poor and exhorting believers to live holy lives. Nevertheless, he had not received and believed the gospel. In his own words, Wesley was an “almost Christian.” Near the end of his Sermon on the Mount, in a passage the lectionary pairs with Paul’s thesis statement, Jesus warns his hearers, “Just because you pray, “Lord, Lord,” does not mean you will enter the kingdom of heaven. Only the one who does the will of my Father in heaven will so enter.”

And the gospel makes God’s will clear and inexorable. God justifies us by speaking promises. Therefore, it is the will of the Lord that you trust those promises.

“Not everyone who says to me, “Lord, Lord,” will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only one who [has faith] will so enter.”

Whereas Luther hated God, Wesley feared him. The Lord who demanded perfect obedience under the law riddled him with anxiety. But then! On May 24, 1738 at a quarter to nine in the evening, John Wesley sat in reluctant attendance at a Bible study on Aldersgate Street where he heard a member read Luther’s Preface to Paul’s Letter to the Romans. And the power of the gospel got him; he broke through.

Wesley writes:

“While Luther was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone, for salvation; and an assurance was given me that He had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death.”

Again and again, whenever the church has awakened from its static, slumbering status quo the crater left behind is the explosive apostolic gospel Paul proclaims to the believers in Rome.

Just over a century ago, Karl Barth was a pastor of a little church in a working class village in Switzerland when he learned that all of his former teachers in Germany had signed an official endorsement of the Kaiser’s war effort. Concluding that his liberal theological education was rotten at the root, Barth set out to rediscover the gospel for himself. Barth went to Paul’s Epistle to the Romans where he broke through:

“Paul’s gospel [of Christ apart from works of the law] has stood always on the brink of heresy…And yet, any reader ought seriously to reflect whether this persistent covering up of the dangerous element in Christianity is not to hide its light under a bushel.”

In Paul’s thesis statement, Barth discovered that the one way love of God announced in the gospel is simultaneously a powerful judgement on the “criminal arrogance of religion and all other human projects.”

The “Yes” of the gospel is for the Jew and the Greek exactly because the gospel is first a “No” that is all-encompassing.

God justifies us by speaking promises.

We are justified only by God speaking promises.

Thus, the gospel’s Yes is also God’s No against all other attempts to accrue righteousness.

Though he was not an academic, Barth’s commentary on the Epistle to the Romans “exploded like a bomb on the playground of the theologians.” Just so, Barth’s reclamation of the gospel laid the groundwork for the Confessing Church’s resistance to Nazism during the next world war.

Again and again, God’s gospel in Paul’s letter has freed the church for joyful obedience.

The church’s task of gospeling merely attempts to say what Paul proclaims to the church at Rome, a promise with the power to produce a question like, “What story?”

As the New Testament scholar Frederick Dale Bruner translates the verses:

“For I am not ashamed of the gospel, for in this news is opened up and poured out a perfectly right relationship from and with the true God and this relationship is received by simple faith.”

Unlike his other letters, the reason Paul writes to the church in Rome is not explicitly stated. While the why of the epistle is unclear, the who is detailed. At the end of chapter sixteen, Paul signs off with his greetings to his readers and the list of addressees surprising. Most of the names Paul names are women’s names, including Junia, whom Paul calls an apostle. In addition to women, several of the names Paul names are slave names. And at least two of the names Paul names are prisoners.

That is—

To people chiefly characterized by weakness and oppression, people who live at the beating heart of the empire that made Mary’s boy Pilate’s victim, Paul writes that the gospel is the dynamis (power, dynamite, TNT) of God invading the world to do what only God can do, speak into existence a right relationship with him that has none of your fingerprints on it.

One way love apart from an iota of anything added by you.

This is precisely why Paul must stipulate that the gospel is simultaneously a potential source of shame. The reason the church so often drifts from the gospel is that the gospel is offensive.

As Luther writes:

“The sum and substance of this letter is this: to pull down, to pluck up, and to destroy all wisdom and righteousness of the flesh, no matter how heartily and sincerely they may be practiced.”

In other words, no righteousness that comes from us— not our good deed doing, not the purity of our hearts, and not the zeal of our piety— will endure before God. God’s Yes is also first God’s No. God in his gospel assaults the pious and the pagan alike merely by speaking a promise to which the only response is faith.

To make it plain—

If the message does not elicit questions like:

“Shall we sin the more so that grace may abound?”

“Is the law to no avail?”

“Can I then do nothing?”

If the gospel does not provoke such questions— if the gospel does not bring you to the precipice of heresy, if the gospel does not strike you as “a dangerous element” in Christianity— then it is not the gospel.

Paul has to make explicit that he is not ashamed of the gospel because the gospel is offensive to EVERYONE BUT GOD.

The gospel is the great leveler, for everyone who is saved is saved in exactly the same way.

The church does not have valedictorians— not even an honor society.

Everyone who is saved is saved in exactly the same way.

Faith.

Alone.

Apart from works.

Which is to say, irrespective of your goodness or your badness.

I remember the time and day and place that I broke through.

It was a Wednesday afternoon in October in 2002. It was a hot Indian summer day and the gathering space for worship at Trenton State Prison felt claustrophobic with humidity. Large outdated fans pushed the thick air around the room and sweat gathered on the top lips of the guards.

Sister Rose led the inmates through the simple liturgy and, as the assistant chaplain, I preached a homily on a passage from 1 Corinthians quite like Paul’s thesis to the Romans. After the service finished, as Sister Rose and I took down the makeshift altar and some of the men stacked chairs, a small inmate with an oily face and long fingernails named Christopher crept up to me. This was his second or third time in worship.

“What you said— what you preached— about how God give Jesus for the forgiveness of our sins,” and then he patted his chest, “I’m here for that.”

Not catching his meaning, I nodded and invited him to come back next week.

“Nah dog,” he said, “I mean, if what you preached is God’s promise— then I believe it. I take him at his word. I have faith.”

I smiled, about to give him a lame attaboy.

But he wasn’t done.

Nor was God done with me.

Quickly, Christopher followed up his profession of faith with an uncomfortable question.

“I have faith. So, that means even after everything I done, I’m right with God?”

I hesitated.

I stalled.

The reason?

In that prison, like many prisons, the inmates who attended the Christian worship service did so because the nature of their crimes was such that church was the only place in the prison outside of their cells where they safe. Most of my congregants at the prison had committed unspeakable assaults upon the most vulnerable population, crimes that— almost to the person— had been perpetrated on them when they were children too.

Christopher was naive enough to think I hadn’t heard him.

“Preacher, I said I believe. I take God at his word. Does that mean I’m right with God?”

To say yes ran counter to every conception of justice and morality I knew.

From behind me, I heard Sister Rose clear her throat and in her Kindergarten teacher’s voice whisper, “If you can’t say yes, Pastor Jason, then you should be attending Mass with me this Sunday.”

I nodded, first to her and then to him.

“Yes,” I said to Christopher, “Yes, you’re justified.”

And Christopher smiled and then exploded in tears, like a chain somewhere within him broke loose.

“That’s crazy!” he laughed with new life.

“No,” I said, “It’s God’s gospel.”

After he’d settled and wiped his eyes, Christopher looked at the two of us and asked if he could confess the sins that no longer condemned him. Sister Rose gestured us to sit at two of the remaining chairs. I sat facing him and we both leaned over to pray and I listened and gritted my teeth as he confessed crimes so ghastly I hope one day I can forget ever having heard them.

When Christopher was done confessing, I put my hand on his head like Sister Rose had taught me. I laid my fingers in between his unkempt corn rows. His head was hot and sweaty and greasy and I felt certain the Lord— or maybe his Enemy— was testing me to see if I’d do the deed and hand over the goods.

“In the name of Jesus Christ…” I began.

He cried again as I absolved him of his sins.

When we were done, he stood up and straightened his khaki uniform.

“Thank you for listening to my story,” he said to me.

Immediately, I thought of that afternoon sipping sherry with Dr. Hartt, and I replied to Christopher, “What story? It’s gone now. It belongs to the Lord Jesus.”

As he walked away, Sister Rose looked into my eyes and asked, “What are you thinking?”

“I’m thinking I just became a Christian— for real,” I said.

Christ apart from works.

I’d broken through.

While the good news is good, the good news is not new.

At the top of his epistle, Paul insisted that God’s gospel is the very same promised that the Lord laid on the lips of Israel’s prophets. As a for instance, in his thesis statement Paul points back to the prophet Habakkuk, “The righteous shall live by faith.” Indeed Luther believed these verses operated as our entrance into the Old Testament exactly because Israel’s scriptures make the selfsame promise as the gospel.

For example, Jeremiah tells sinful Israel, “The Lord is our righteousness.” The prophet even goes so far as to posit this promise as the people’s own name, "And this is the name by which Israel will be called: ‘The Lord is our righteousness.’” The Lord— not our commandment keeping— is our righteousness. The promise in the mouths of the prophets is no different than the gospel given to the apostle; namely, the gospel frees you from the accusation of the law because through the gospel God gifts you a perfectly right relationship with him.

Ok.

How? How does the gospel give you a right relationship with God? You might be worse than Christopher. How does this work exactly?

Luther’s answer:

God creates by speech; just so, God can create righteousness by speech too. Therefore, while righteousness cannot be earned, it can be promised.

To believe in God’s promise as Abraham did is to be right with God.

Because faith honors God.

Faith says to God what any lover longs to hear from their beloved, “I believe what you say. I take you at your word.”

Thus, the gospel is but the obverse of the first commandment, “I am the Lord your God— you are mine; I’ll never let you go.”

Last Sunday I preached for a congregation in Southern California.

After the morning service, a parishioner embraced me and thanked me on the way out. “Thank you for preaching the gospel,” she said, “Forgiveness. On account of Christ. For you. I heard it last Sunday and I’m so relieved you handed it over this Sunday.”

I must’ve looked at her quizzically because she elaborated.

“Somewhere between Monday morning and last night I stopped believing it. I needed to hear the gospel this morning.”

Here’s the thing—

If the gospel was about morality or justice, then I should’ve asked what she had done to so need the word that frees her. But Christ doesn’t call us to ask questions. He sends us to hand over promises.

As she turned to walk to her car, I asked her a question.

“Tell me,” I said, “not many listeners respond that way to preaching. How did you learn that’s what you’re supposed to be listening for in a sermon?”

She looked at me like the answer was so obvious the question must be a trick.

“The Bible?” she said, and then she added, “If the gospel is the explosive material, why would we waste our time with anything else?”

As Protestants, we believe that Jesus is present in the loaf and the cup, not through any philosophical abracadabra of substance and accidents. We believe the bread and the wine are his body and blood simply because the Lord Jesus told us so.

We take him at his word.

And therein, taking the loaf and the cup we are justified.

The bread and the wine in our hands and on our lips just is our righteousness.

Which makes you coming to the table the church’s only altar call.

So break through.

And come to the table.

Share this post