Revelation 21.1-6

There is a wonderful crescendo at the end of a famous sermon by the ancient church father Leo the Great, in which the fifth century preacher riffed on the two little words, “pro nobis.”

For us.

For us, he got up off his knees in Gethsemane.

For us, he carried his cross to Calvary.

For us, he surrendered his hands and his feet and his breath.

For us, he entered into death.

And storming the gates of hell, he harrowed it— for us.

Over ten years ago, in the days after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut— days which were deep into Advent— I referenced Leo the Great’s sermon in a reflection I wrote for my congregation:

When it comes to Christmas (and Christianity in general, for that matter), we tend to think the operative word of the season is “for.” Christmas is a time we feel drawn to doing things for others.

“For” is our operative Christmas word.

But that’s a problem. Because “for” despite all its good intentions, can’t repair broken the relationships between us, ease the alienation amongst us, or keep the poor from remaining strangers from us.

More fundamentally, our fixation with “for” at Christmastime is problematic because “for” isn’t the way God celebrates Christmas. Remember, the angel says to Joseph, “Behold, the virgin shall bear a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel,’ which means, “God is with us.”

With.

It’s a tiny little word but it gets to the heart of Christmas.

In fact, with is the most important word in the Bible. Scripture testifies that God’s grace in Jesus Christ is “the beginning of all the ways and works of God;” therefore, God’s whole life and action and purpose are shaped to be with us.

One of the lessons we discover when we refuse to run away from the sorrow of those mourn is that with is a lot more difficult than for. For doesn’t require a conversation, a real relationship, or any change in your own life to incorporate the other. What makes a gesture like “thoughts and prayers” ring hollow is not that they’re necessarily ill-intentioned, but that what those who weep the tears of Jesus need is not words for them but the faithful presence of a people who will be with them.

But with can be scary because the with seems to ask more of us than we can give.

And that’s why it’s gospel, good news, that God didn’t settle on for.

At Christmas, God said unambiguously, “I am with you. My name is Emmanuel, God-with-us. And how do we celebrate this good news in a world seemingly bereft of any? By being with people in their distress, even when there’s only so much we can do for them. By being with one another as an end in itself. By being with God in word and wine and bread rather than rushing in our anxiety to do or say, type or tweet, yet more things for God and others. More so than for, with is the word that gets decisively to the crux of the Story God is creating.

“And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, ’See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them.”

The Father only speaks to us in the Gospels two times.

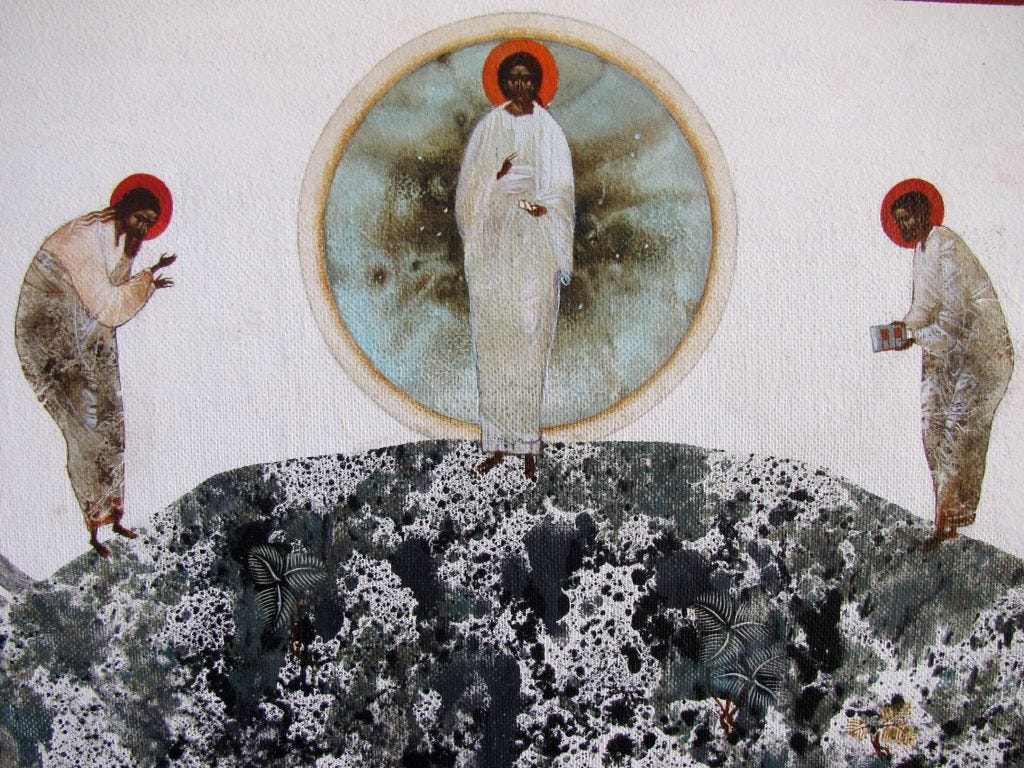

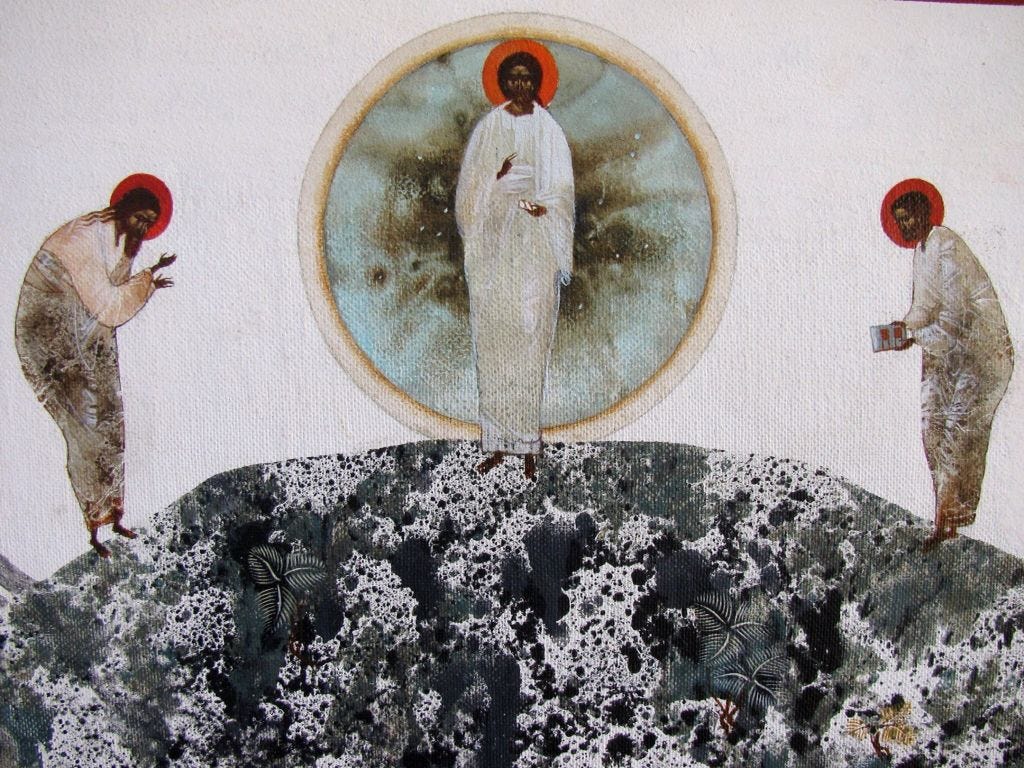

The first time God speaks is at Jesus’s baptism in the Jordan when the Father declares, “This is my priceless Son, with whom I am well-pleased.” The second time the Father speaks to us is on the high mountain where Jesus is transfigured before Peter, James, and John. Both times the Father speaks in the Gospels it’s to signal his identification with the Son who is likewise Mary’s boy and soon will be Pilate’s victim.

That the Transfiguration is just the second time the Father speaks in the Gospels is the interpretative key, for it discloses to us that the Transfiguration signals not an alteration in Jesus but a revelation of Jesus.

The disciples experience an epiphany. They experience what alcoholics call a moment of clarity. They see briefly who Jesus has been all along.

In the words of the church father, St. John of Damascus:

“Christ is transfigured, not by putting on some quality he did not possess previously, nor by changing into something he never was before, but by revealing to his disciples what he truly was.”

As Jesus shimmers with the uncreated light of God’s glory, Moses and Elijah appear on the mountaintop alongside the incandescent Christ. Of the three, only Jesus is like the Burning Bush, afire with the kabod of the Father but not consumed by it. The disciples see what the creed says— that Jesus is “Light from light, true God of true God, of one being with the Father.” Later in his life, recalling his glimpse of glory, the Apostle Peter will write in his second epistle that, looking back, the Transfiguration was the defining experience of his life.

In the moment, however, Christ’s transfiguration is more reality than the disciples can bear.

As before in the Gospels, Peter fills his fear with words:

“Lord, it is good for us to be here; if you wish, I will make three tabernacles here, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.”

Tellingly, Jesus does not once again rebut Peter, “Get behind me, Satan!”

Jesus says not a word.

In fact, the Mount of Transfiguration is the only instance in any of the Gospels where Jesus does not respond at all to something someone has said to him.

The Transfiguration is the only instance where Jesus offers no reply.

Thus, Peter is not completely wrong.

He is more correct than we typically credit him.

It is good to dwell with Christ.

Indeed dwelling with God as God is your destiny from before the foundation of the world.

“I will be your God,” the Lord uttered in his primal promise, “and you will be my people.”

Peter’s mistake is not in wanting to abide on the mountain and dwell with God.

Peter’s mistake is thinking that Jesus, Moses, and Elijah require three tabernacles when they need only one dwelling place.

Peter’s mistake is not realizing that Elijah and Moses are not separate from Christ.

They are already in Christ.

With him.

In him.

He is their home.

Ellen Baxter is the founder of Broadway Housing Communities in New York. In the 1970s, as a psychology student at Bowdoin College, Baxter set out to discover a more humane way to treat the mentally ill.

As an undergraduate, she faked her way onto a psychiatric ward with a bogus diagnosis of dangerous depression so that she could observe how the patients were treated.

She left convinced that American culture's obsession with improving and fixing and changing ourselves had infected the mental health system too.

We're stuck on recovery, I heard her tell NPR.

We're stuck on recovery, but when you fail to deal with people as they are, when you're dead set determined to do things for them, fixing them and changing them, you end up changing them for the worse.

Because you erode their humanity.

Ellen Baxter's research through old medical journals and psychology articles led her to a modest village in Belgium named Geel.

According to those dusty journals, Geel had the highest success rate of recovery for the mentally ill.

At the center of Geel is a church dedicated to Saint Dymphna, who was martyred in Geel in the seventh century.

Saint Dymphna is the patron saint of the mentally ill, which is why, beginning in the eighth century, Geel became a pilgrimage destination for the mentally ill.

Five centuries later, starting in the 13th century, the residents of Geel began boarding those pilgrims into their homes.

Geel became a place where everyday people, farmers, bartenders, blacksmiths, ordinary people, welcomed the mentally ill into their homes, no questions asked.

Just as they were.

No matter the risks.

Welcome them like you would a beloved aunt or uncle.

By the 19th century, this practice of hospitality earned Geel the nickname “Paradise for the Insane.”

And by the turn of the 20th century, this Christian practice became a public system where doctors now place patients into the homes of hosts who have no idea what diagnosis their guests bring with them.

By 1930, over a quarter of all the residents of Geel were mentally ill, about 12,000 people.

According to Ellen Baxter, the average length of stay for a guest with a host family— and notice they call them guests, not patients— the average length of stay for a guest is 28.5 years.

More staggering, in Geel a third of all of the guests stay with their host foster family for almost 50 years.

They take these broken, crazy guests into their homes, and they live with them. In many cases, they die with them.

Baxter won a grant fellowship to study for a year in Geel.

She describes going from house to house in Geel, interviewing foster families, asking the same questions, and always getting the same answers.

“Do you find it to be a burden?”

“No."

“Do you find it tiring?”

“No.”

“Do you find it painful?”

“It's just life,” the bus driver told her.

“Over and over again,” she says, “I heard the same response from host foster families.

Host families would shrug their shoulders and reply that “crazy” is just a part of normal life.

It made me wonder if I had stumbled upon a race of angels.”

But Ellen Baxter says she still didn't understand why the villagers of Geel were so successful at rehabilitating guests, more successful than modern medicine.

And these are people with serious mental illnesses.

She didn't understand what made it all work until she met someone that she calls “The Buttons Guy.”

The Buttons Guy was a middle-aged man, a boarder, who every single day would twist all the buttons off of his shirt, nervously twirl them off slowly every single day.

And every single night— every single night— his host foster mother would sew all the buttons back onto the button guy's shirt.

Every day for 30 years, he twists them off.

And every night, she sews them back on.

"What a waste of time,” Ellen said, she said, when she first heard the foster mother describe what she did in order to live with the Buttons Guy.

“You should sew the buttons back on with fishing lines so he can't twist them off."

And the host mom reacted with something like offense.

“No. No, that's the worst thing you could do,” she said. “This man needs to twist the buttons off. It helps him to twist the buttons off every day. You don't understand,” she explained, “In order to accept the mentally ill into your home, you first have to accept what they're doing. You have to accept their oddness and their idiosyncrasies. You've got to let them take their buttons off.”

“Being with them, she told Ellen Baxter, “is the first step in being able to do anything for them."

And that's when Ellen Baxter stumbled upon what she calls the “Solution of No Solution.”

Once she knew what to look for in Geel, she said she saw it practiced from house to house.

What freed guests for healing and rehabilitation was the way their hosts refused to treat them as people with problems to be fixed.

Instead, they just welcomed them into their homes to share life with them.

The hosts’s acceptance of their guests without any expectation of changing them is itself the elixir with the power to change them.

Ellen Baxter calls what she found in the homes of Geel, quote, “The strange healing power of not trying to fix the problem for them.”

The strange healing power of that little word.

With.

A decade ago, I concluded my letter to the congregation thusly:

If we are to offer our thoughts and prayers for those who sorrow, then let us pray rightly. As Robert Jenson insists, "We pray to God (the Father) with the Son and in Jesus’s Spirit. If we only pray to God, if our relation to God is reducible to the ‘to’ and is not decisively determined also by “with” and “in,” then it is not the true God whom we identify in our address, but rather some distant and timelessly uninvolved divinity whom we have envisaged…

The particular God of scripture does not just stand over against us; he envelops us. And only by the full structure of the envelopment do we have this God-who-is-with-us.” If there is any hope in this present evil age, it’s praying with Jesus, in his Spirit, to the God who has promised to be come and be with us.

Only that compact, conclusive word alone— with— can rectify what is wrong with us.”

The serpent says to Eve in Eden, “You will not surely die. For God knows that when you eat of the fruit of the tree…you will be like God.”

The last book of the Bible reveals what had been hidden in the first book’s opening chapters.

The serpent is not wrong.

Satan’s trespass is not to lie.

The Tempter’s trespass is to give away the plot of the Story.

Death will be behind us.

We will know God as God.

And just so, we shall be like him.

This is what the prophet sees and hears in the Apocalypse’s penultimate chapter.

The picture John sees matches the promise he hears:

“See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them.”

But then— notice— the prophet does not see God the Father.

Even in the Fulfillment, the Father’s infinity exceeds our grasp.

“God is unknowable in two senses,” Robert Jenson writes: “first, when we know God, we embark on an act that can never achieve rest, since it is finite knowledge of an infinite object; second, the very completeness of his revelation hides him. When God is all in all, these two come together. God will be more and more unknowable for being so intimately known. In God, we will know that he is infinitely beyond us. And this experience will be precisely the experience of his glory and of our participation in it. Even in the light of eternal beatitude, God is only known by being forever sought.”

Even at the End, the Father is a figure unseen.

Instead John sees the dwelling place descend from heaven to earth, already prepared by God.

The Tabernacle that is the New Jerusalem measures 12,0000 stadia— 1,500 miles— in every direction. Thus the City of God is a perfect cube. “It lies foursquare,’ John reports, “its length the same as its width.”

That is, the Kingdom is a perfect cube.

Just like the inner sanctum in Israel’s Temple.

In other words, it is the Holy of Holies stretched to an infinite size fit for all.

The Lord will be our dwelling place.

And since only God can dwell in the Holy of Holies, it follows that shall be made like him.

Therefore, being taken into the heavenly home will simultaneously be our healing.

On the mountaintop, Peter was only wrong about the number. To Eve in Eden, the Tempter’s trespass was not to lie. Like Peter, the serpent is correct. The Tempter’s trespass was to give away the plot prematurely.

We will be like God and live with death behind us.

The Tempter’s trespass was spoiling the plot.

But then, so did the ancient church fathers when they summarized the gospel with the slogan, “God became what we are; so that, we might become God.”

God means to make us like him.

And God means to make us like him precisely by welcoming us into the home that is him and dwelling with us— we who are so disconnected from reality if it is true that Jesus Christ is Lord.

“God became what we are; so that, we might become God.”

Ellen Baxter describes another guest she met in Geel named Des. Des suffered tears every night that bloodthirsty lions were about to pounce through the walls to eat him. It wouldn't work to tell him the lions aren't really there. It wouldn't work to try to convince him that he should change and be not afraid, his foster mother, Tony, explained. Instead, every night, Tony and her husband would rush outside, banging pots and pans and roaring like lions themselves to scare the lions away. And that would work every time, Tony explained. He could rest. And then, eventually, one day, Des wasn't afraid of the lions anymore. And then, one day, the lions weren't there anymore.

“But this is important,” she said, “Making him unafraid of the lions, curing him of his tears, was not our goal. Our goal was simply to welcome Des into our home, just as he was, and to share our life— and here’s that little word again—with him. Only that with has the power to transform.”

In other words—

With is the ultimate For.

Look, maybe you don't twist the buttons off your shirt day after day. And you might not think lions are about to leap out of the walls. But we all suffer delusions. We all fall prey to seductive fictions. And we all hear voices.

I mean, some of you might be crazy enough to think that you're basically a good person and, like Peter, you think you can build a tabernacle for yourself, all by your lonesome, alongside Jesus. Some of you might be so insane, you actually think your sins are too great for Jesus Christ to have forgotten them forever in his grave. And some of you might just be deluded enough to think God’s going to evict you from the Last Tabernacle on account of your outstanding debts and poor credit history— your resentments and your jealousies, your broken relationships and your bitter strings of regret.

That's plain crazy.

We all suffer delusions. And we all hear voices in our heads. Voices telling us that we are unlovely or unloved or unlovable, voices telling us that we are inadequate or unforgivable, voices that never tire of pointing out all the ways we fall short of a standard that exists only in our heads, voices that never quite go away or quit their whispering.

Those are delusions.

But don’t beat yourself up, not a one of us is well.

So here the good news— spoiler alert:

The most important word; the little word with strange, healing power; the compact, conclusive word that is a solution that looks like no solution at all, God’s with is a word on which you need not wait.

As John Behr says, the earliest Christians referred to them as “passages of scripture” because if we sit patiently with them, like Elijah nestled in the crook of a rock, God will pass by us and, for a little while at least, dwell with us.

As Jesus says, ask, seek, knock and the Lord will answer his door to you.

With is a word on which you need not wait.

Every humble prayer, every sitting with scripture— the Lord dwells there.

With is a word on which you need not wait.

The Lord comes to you, just as you are, with all your sin and insanities, without trying to fix you first, and he takes up temporary residence in the words of my mouth, at font and table.

The most important word is a word on which you need not wait.

Every gospel word, every creature of water, wine, and bread is a tabernacle of the Lord and thus, for us, they are paradise for the insane.

Some come to the table, the operative words there may be “For you…” but Christ is the host and, therefore, the for is secondary to a more ultimate and healing with.

Share this post