Genesis 33.1-11

You know the story.

The begrudgers were grumbling, “This Jesus welcomes sinners— tax collectors, even, Jewish enablers of Israel’s imperial enemy. This rabbi welcomes the very worst sinners among us, eating and drinking and who knows what else.”

So Jesus reaches for his holster and quickly fires off three parables. The first about a lost sheep. The second about a lost coin. And then, a parable about lost brothers.

“There was a man who had two sons,” Jesus says.

“One day, out of the blue, the father’s youngest son wishes his Daddy dead, demands his share of his future inheritance right now. Continuing a pattern of poor biblical parenting, the man calls his realtor, sells off half his land and the livestock on it, and hands over a cashier’s check to his rotten kid.”

“And wouldn’t you know it,” Jesus says to the begrudgers, “The ingrate takes out a ridiculous lease on a tricked out ride and peels off to live it up in the far country, but he hadn’t even emptied his third tank of gas by the time he’d squandered away his entire inheritance.”

Seeing the begrudgers raise their eyebrows at his story, Jesus adds, “Just like that, every last shekel was gone, use your imagination as to how. So the kid’s broke and homeless and, having no resume, he hires himself out to tend pigs— not a very good job for a Jewish boy. Before long— his boss hadn’t yet Venmo’d him his first week’s pay— the boy is so desperate he’s slurping up the slop the pigs are eating.”

And Jesus catches the look of disgust that creeps over the begrudgers faces.

“I know, right?” Jesus says, “It’s gross.”

“Anyways,” Jesus says, “As I was saying, the snotty kid’s on his knees at the pig troth as though it was a seat at the table and it occurs to him that even his old man’s servants have it better than his present circumstances. The boy says to himself, “I will get up and go to my dad, and I will say to him, “Sir, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me like one of your hired hands.”

“So the kid hitchhikes his way home, and while he was still just a dot on the horizon line, his old man sees him. Evidently, his father’s been sitting on the porch every day hoping his prodigal son would return. His father sees him and immediately he does what no respectable Jewish father would do. He gathers up the hem of his garment and he sprints down the driveway, blubbering all the way. With big, ugly tears in his eyes, he throws his arms around his son and kisses him so ferociously the kid can only mumbled the speech he’d prepared, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son.”

“But the father didn’t even hear his apology. He was already too busy pivoting into party-planning mode, snapping his fingers at his servants, “Quickly, bring out a robe—the best one—and put it on him; put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. And get the fatted calf and kill it, and call the DJ we used for the bar mitzvah last month. Let us eat and celebrate; for this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!”

“And then,” Jesus whispers with a dramatic flair, “Just when the meat hit the grill and the beer had been dumped in the cooler, the father’s elder son returned from mending the fences.

“He heard the commotion and he smelled the barbecue so he asked the help what was going on. The servant replied, “Your brother has come, and your father has killed the fatted calf, because he has got him back safe and sound.”

“Hearing the news, the elder brother tossed his tool belt on the ground and ran down to meet his brother and, throwing his arms around the prodigal, the elder brother exclaimed, “Of course, we have to party! We have no choice, or this brother of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!”

No.

You know the story.

You know that’s not how the story ends.

But that is, more or less, how this story ends in the Book of Genesis.

Other than their divergent endings, the similarities are so striking there’s no way Jesus wasn’t thinking of Jacob and Esau’s reconciliation when he told his story of two brothers.

Having wrestled with the Lord Jesus until daybreak, Jacob finally realizes he has reached the limits of his capacity to manipulate events. His elder brother Esau is near, and Esau is determined to be Cain to Jacob’s Abel. Accordingly, Jacob has just prayed an insistent, desperate prayer— the longest prayer in the Book of Genesis— demanding that God make good on the promise he pledged to Jacob. Remember, the last words Esau uttered in scripture swore vengeance, “I will kill my brother Jacob.” Indeed the two brothers have not spoken to each other since the younger swindled the elder out of his birthright.

So Jacob prays a long petition in the chapter prior, placing his future entirely in God’s hands. Limping his way past the place he names Penuel, Jacob lifts up his eyes and, like a dot on the horizon line, he sees his bloodthirsty brother approaching him. Actually, it’s more like lots of dots on the horizon line, for the unsubtle Esau leads four hundred men with him.To his credit, Jacob does not use his family as human shields; instead, he ventures out in front of them, alone.

Jacob limps towards Esau.

And then he bows in deference.

He limps towards Esau.

And then he bows down in submission.

He limps.

And he bows.

As though it’s a full-bodied confession, “I have sinned against heaven and against you. I am no longer worthy to be called your brother…” Seven times, scripture says, the younger son limps and bows, all the while making his way to the father’s elder son who has pledged to kill his brother. But when the vengeance he’s sought is finally in front of him, Esau responds by breaking his promise. He does not do what he’s vowed to do.

Or rather, the Lord keeps his promise to protect Jacob by willing Esau to forsake his promise to kill Jacob. Like a prodigal father, Esau runs across the would-be-battlefield, throws his arms around his brother, falls on his neck, and kisses him— weeping from the start. “We have to party! We have no choice, for this brother of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!”

The end of the story is almost too good to be true.

“This is surely the hand of the highest,” Martin Luther comments on the two brothers’s reconciliation. The God who can stay the proud waves of the sea is the same God who can stop the fury in the heart of Esau. In other words, this ending, this resolution, it’s a miracle. In the end, Luther argues, Esau is “not conquered by strength, diligence, plans, evil tricks, or pretense, but solely by the goodness of God, for Esau’s will is changed.” Thus Jacob, Luther contends, belongs to the number of those of whom Christ says, “All things are possible to him who believes.”

Perhaps.

Maybe the end of the story is too good to be true.

Maybe the end of the story is too good to be true just yet.

If you read further into chapter thirty-three, you discover that the brothers’s miraculous reconciliation does not lead to happily ever after.

Esau invites Jacob to join him on the journey to Seir.

But Jacob dodges the invitation and says, “Yeah, um, you know how it is, a long car ride and all. The kids are tired and the lambs are nursing right now. You go on ahead, brother, and I’ll follow after you just as fast as the livestock will allow.”

Esau journeys on to Seir.

And Jacob journeys to Succoth, which— you have to know your Bible geography to catch the clue— is in the opposite direction of Seir.

It’s the equivalent of Jacob promising to meet Esau in Baltimore and then heading towards Charlottesville. Combine this little detail with the fact that both the Book of Exodus and the Book of Numbers depict Esau and his descendants as enemies of the people of Israel.

“We have to party! We have no choice, for this brother of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!”

It’s not simply that the end of the Jacob and Esau story outdoes even Jesus’s own story of lost brothers; it’s that the prodigality of their reconciliation (the lavishness of it, the weeping and kissing and embracing, the over the top talk about seeing the face of God in the other) it cuts against the grain of the larger biblical narrative.

For this reason— pay attention now:

Both the old rabbis of the Synagogue and the ancient fathers of the Church, interpreted this scripture eschatologically; that is, this scene with which the story of Jacob and Esau ends it points to the End with a capital E.

After all, the very first principle of interpreting scripture is that scripture interprets scripture, and the apostle Paul makes it explicit in his epistle to the Romans that Jacob and Esau function respectively as figures for the Church and the Synagogue. Jacob is the Church, the younger sibling who, according to the purpose of God, has taken the birthright of the older brother.

“Does this mean God has rejected the elder brother, Israel?” Paul asks before quickly answering, “By no means!”

It’s all in service to the salvation of the world, Paul writes.

What God does with the few, what God these two, Jacob and Esau— God does for the many. It’s for all. Esau’s embrace of Jacob foreshadows the reconciliation of all things by the thin, narrow line of God’s election, first of Israel and followed by the Church.

Esau then Jacob.

It’s about how the Story with a capital S will End.

It’s about Synagogue and Church.

It’s about Jews and Christians.

It’s about what we ultimately make of each other and what finally God will make of us.

A few of years ago, my wife and I were traveling in Southern France.

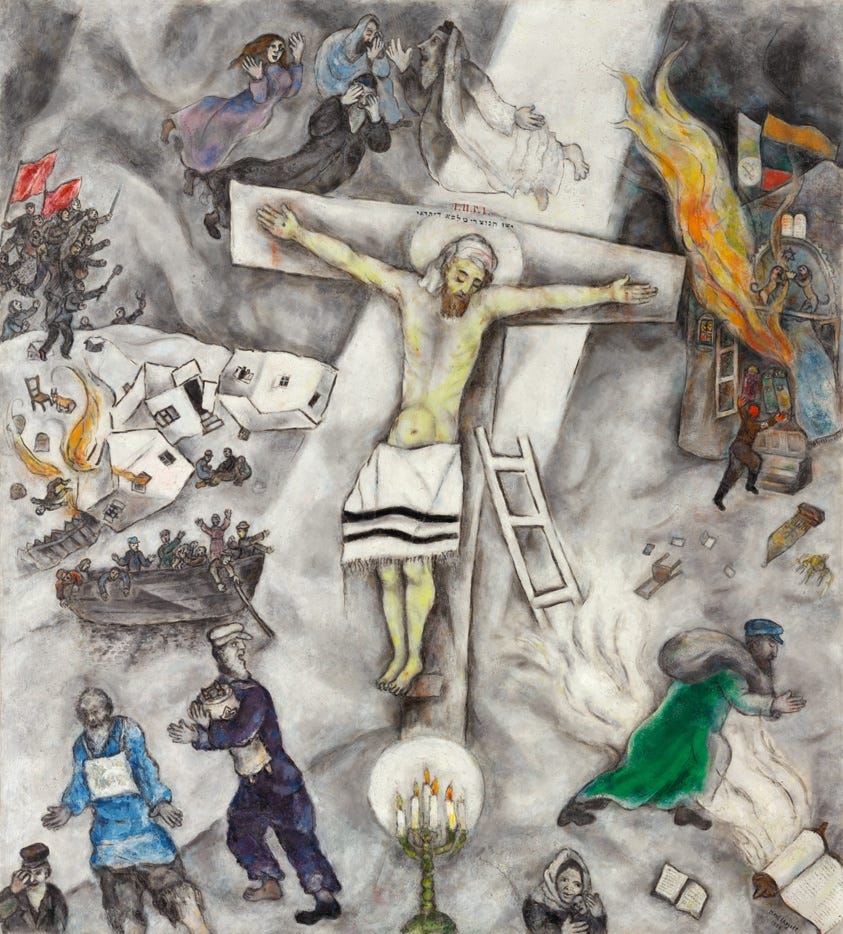

On one hot, sunny day we toured a museum in Nice devoted to the work of the artist Marc Chagall. A Jewish artist, Chagall had been born in Russia but fled to France before the outbreak of World War II. The museum is a series of large, round rooms with Chagall’s boldly colored art displayed against spartan white walls. Because of the diversity of tourists, there was no single tour guide per se. Instead everyone was given a hand-held radio each set to a specific language with numbered buttons that corresponded to the numbers next to each section of paintings.

Holding the radio next to my ear, I worked my way through the museum in no particular order. After a while, because my feet were sore, I sat down on a long leather bench in the middle of a gallery floor next to an old man. He had a yarmulke clipped to his white, wiry hair and, faintly, I could hear that his radio was set to Hebrew.

Like the old man sitting at my left, I stared up at the painting entitled White Crucifixion:

I pressed the button on my radio, button fourteen, and I listened as the GPS-sounding voice explained how Mark Chagall, who’d studied Torah before he’d studied art, saw in Jesus of Nazareth the ultimate symbol for the suffering of all the Jewish people. When the GPS-sounding voice went on to mention how earlier versions of White Crucifixion depicted soldiers in black with swastikas on their arms burning down a synagogue, I heard the old man next to me start to cry. His palsied hand was holding the radio up to his left ear. Just underneath the cuff of his white sleeve I could see the numbers tattooed on the inside of his left wrist.

Like a tag on an animal.

Or a barcode on a piece of supermarket meat.

It’s not a trivial matter that both the rabbis and the apostles read this scene of reconciliation eschatologically, as a sign of the day when Jews and Christians would embrace one another in the life everlasting that is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

On November 9, 1938, Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, a twenty-two year old boy named Emile Fackenheim managed to escape as Nazi storm troopers ransacked and burned Jewish homes and businesses and synagogues and then took thirty thousand men to concentration camps. Emile Fackenheim went on to become the most important Jewish theologian of the twentieth century. Fackenheim wrote a book of post-holocaust philosophy called To Mend the World.

In that book, to all those who worship the God of Abraham, Fackenheim issued what he calls the 614th commandment. According to the rabbis reckoning, the Old Testament contains 613 commandments. Because of the enormity of the Holocaust, Fackenheim argued that those who worship the God of Israel should add one more commandment to the list, a 614th Commandment.

Commandment #614 goes like this:

Thou shalt not give Hitler any posthumous victories.

For Jews, Fackenheim argued, the 614th Commandment means they should not despair. They should not despair that this is God’s world and they are God’s chosen people.

And for Christians, the 614th Commandment means we should remember that the New Testament itself insists that God wills not only the existence of the Church but God wills the ongoing existence of the Jews as Jews.

According to Paul, the people of Israel have an abiding and irremovable place in the will of God.

Thou shalt not give Hitler any posthumous victories.

Such a commandment requires that we understand not only that God wills the ongoing existence of the Jews as Jews but it requires too that we understand why God so wills.

As politicians increasingly give voice or platform to anti-semitic tropes, it’s all the more urgent we understand why the Jews as Jews remain a necessary part of God’s final intention.

As the Jewish theologian Michael Wyschogrod insists, it is:

“…the fleshly, incarnations character of God’s relation to Israel which makes the Christian claims about Jesus intelligible in the first place.”

When the gospel first ventured out in mission, it collided with a world shaped by the Greek religion of Plato. The devotees of Plato’s religion believed that deity, by definition, is eternal and so immune to time; that is, God is above and beyond history not involved in history as both its author and an actor within it. Deity, the Greeks simply assumed, is pure spirit not matter and certainly not flesh. Jesus’s bodily resurrection from the dead made absolutely no sense to the pagan world into which the apostles took the gospel message just as it remains unpalatable to pagans today.

But Jews, Wyschogrod writes, understand the claim of the gospel even if most find it in fact false.

Thereby, Jews make the Christian gospel intelligible.

While most of Israel still does not find it credible that in Jesus of Nazareth God lived briefly, died violently, and rose unexpectedly, Israel cannot claim that the gospel is alien to the God of their scriptures. Not if:

“Israel’s God can indulge in a little wrestling match with Jacob, or sit down to Abraham and Sara’s cooking, or converse with humans as his own angel; not if all the phenomena the rabbis put together as the Shekinah [the glory of the Lord] are appropriate to him; or if he can establish an earthly address at Number One Temple Avenue.”

In other words, the Jews are our corroborating witnesses.

God wills the ongoing existence of the Jews as Jews because they are our corroborating witnesses.

They themselves may not be persuaded by our testimony; nevertheless, they abide because they are able to testify on our behalf that “Yes, that sounds like something our God, the true God, would do.”

Thursday afternoon I met a woman in the community for coffee. What I had expected to be an innocent get together instead started with her asking me if I would officiate her son’s funeral, “if and when the time came.”

The surprise must’ve registered on my face.

“He’s lost again,” she said, picking absentmindedly at the sleeve of her blue blazer.

“Who’s lost again?” I asked, “How?”

And then she told me about her oldest son, Connor, how he’d struggled with Tourette’s as a kid and how that grew into a struggle with addiction and mental health at the end of high school. A couple of years ago he’d gotten himself clean and stable when one evening while he was jogging a car struck him and dragged him thirty yards and then drove off and left him in the road.

“He worked so hard through his recovery,” she said, dabbing her eyes with her napkin, “He was back, healing and healthy and whole. It was like, in this terrible but miraculous way, he’d been found.”

She stared over my shoulder for a few moments.

“But it didn’t last.”

“What happened?”

“He developed schizophrenia. He started using again. Then he fell into a delusion that’s made him terrified of his father and me. He absolutely believes it and cut off all contact from us. He bounces around from hospital to homeless shelter. We don’t know where he is now.”

“I’m so sorry,” I said.

“His brother and sisters are done with him and want nothing to do with him,” she struggled to say, “and I feel just awful that some days I know exactly how they feel.”

Even “I’m so sorry” didn’t seem too meager a response so I said nothing.

“I can’t stop dwelling on what I did or didn’t do,” she wept, “how I failed him and how I’m failing him now but just wanting to give up.”

I waited for her to finish and for her tears to run out.

When she could look at me, I said to her— no, I promised her:

“On that last bit, I have a particular word to give you. Christ Jesus has authorized me (and I believe he’s sent me here) to speak it to you today. On his authority, I declare to you the entire forgiveness of whatever you’ve done or not done, however you’ve failed and whatever you’ve countenanced. I can promise you that the Lord has nothing but mercy for all of you.”

With the absolution, she discovered another well of tears. After she cried some more, she nodded and was about to speak, but I cut her off.

“Hold on,” I said, “I’m not done. The Lord Jesus has given me some other promises to hand over to you. One day— I promise you— in this life or in the life everlasting, he will be healed. He’s baptized, don’t forget. That means, the Lord Jesus has promised to raise him up. So one day, I promise you, he will be made whole. One day everything that is broken in your family will be mended. One day— it’s guaranteed, either in this life or the one to come, the two of you will throw your arms around each other and you’ll be like that father in the story who says, “Let us eat and celebrate; for this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!”

“God, I hope that’s not too good to be true,” she said.

“It’s true,” I said.

I didn’t add, but I could have said to her, “Don’t take my word for it. I have an older brother. Call him Esau. We may not always agree, but he could vouch for me. He would tell you, “Yeah, that’s exactly the sort of thing our God would do.”