Every year at Passover, to intimidate any pilgrims with insurrectionist aspirations, Pontius Pilate would travel with his Roman triumph from his seaside home at Caesarea Maritima into Jerusalem. There Pilate would spend the week in the palace of Caiphas, whose title was Chief Priest but whose role was more like Mayor. So it’s not surprising that Caiphas’s spacious palace came equipped with a prison in the dungeon.

In the dark hours after Passover, Caiphas’s municipal guard bring the bound and bleeding Jesus from Gethsemane on the Mt of Olives to the jail cell in Caiphas’s basement. I visited it last month. The guardroom contains wall fixtures to attach prisoners’s chains. There are holes in the stone pillars to fasten a prisoner’s hands and feet when he was flogged. Bowls carved in the floor to hold salt and vinegar in order to aggravate the pain of the prisoner’s the wounds. The prison cell itself is a pit carved out of bedrock, about twenty-five feet deep. The only access to the bottle-necked cell is through a shaft cut in the bedrock above. Having been beaten and flogged, on the morning of Good Friday Jesus was bound and then lowered through the hole in the rock by means of a rope harness. Once down there, there is no way out. There is no hope. There is no one. Just outside the palace is where Peter stands by a charcoal fire and says, “Jesus? Jesus of Nazareth, you say? Never heard of him.” For all Peter knew, Jesus may as well have been dead already, hidden like diamond deep in the dirt.

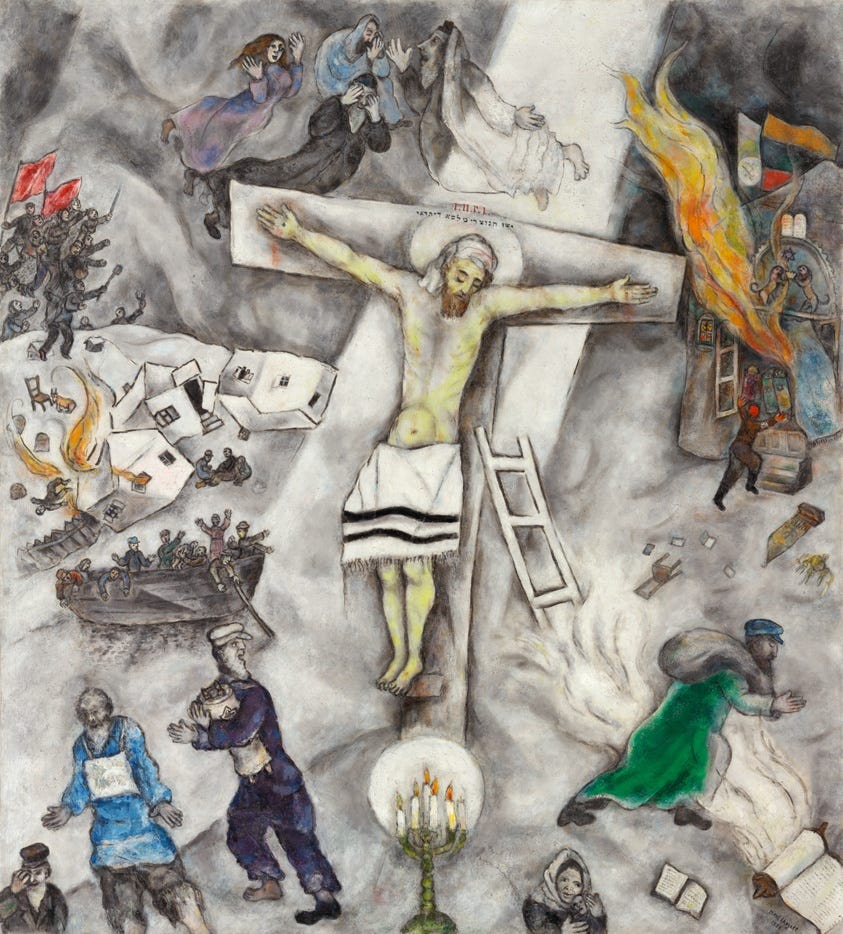

Jesus prays Psalm 22 from the cross.

It’s hard not to wonder if he prayed Psalm 88 in the dark stone hole of Caiphas’s basement,

“O lord God of my salvation, I have cried day and night before thee: Let my prayer come before thee: incline thine ear unto my cry; For my soul is full of troubles: and my life draweth nigh unto the grave. I am counted with them that go down into the pit: I am as a man that hath no strength: Free among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave, whom thou rememberest no more: and they are cut off from thy hand. Thou hast laid me in the lowest pit, in darkness, in the deeps. Thy wrath lieth hard upon me, and thou hast afflicted me with all thy waves.”

If not earlier, there in the pit, that’s surely where Jesus began to cry, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

In Mark’s Gospel, the fourth word from the cross is Christ’s only word from the cross.

As if, in the end, all that Jesus has to say from the cross is all we can say about the crucified Jesus.

He’s been forsaken.

No angel of the Lord will appear to stay the blade in hand. This time the Father will not spare his only beloved Son.

A short walk from Mt. Moriah, where Abraham took his son Isaac to murder him to honor the Lord, we push our Lord up a hill called Golgotha, carrying not a blade and wood for a fire but a cross and a hammer and nails.

Golgotha is Mt. Moriah without the ram in the bush or the angel to the rescue.

Calvary is where the children of Abraham provide the innocent lamb for slaughter, another Father’s Son.

Good Friday is Abraham going through with it.

My God, my God, why do we forsake him?

Why do we cast him into the pit and then crush him on a cross?

Imagine—

Imagine Abraham went through with the deed on Mt. Moriah. Imagine he did it. Imagine Abraham closing his eyes and raising his arm and plunging the knife. Imagine Isaac’s scream and the silence that would follow it, save for the bleating of a lost and forgotten ram amid the bushes. Imagine Abraham making his three day trek back down the mountain path to Isaac’s mother. And imagine a stranger approaching Abraham’s campfire that first night and, in the comfort of the darkness, Abraham confesses to this stranger his story about what he had believed god required, how it led him to violence and murder, how in his grief he knew now that heaven wept with him, how he had been blind and deaf, his faith had been unfaith, how as he plunged the knife he realized he had mistaken the gods for the true God. Imagine Abraham spilling out his shame, and then realizing he’d not even asked for the stranger’s name.

“Tell me your name,” Abraham asks. And the stranger lifts up his bowed head and pulls back his hood and replies, “Isaac.”

And then imagine Isaac showing Abraham his hands and his side.

This is the gospel.