1 Kings 17.16-24

Over twenty years ago, I was part of a captive audience for a class on preaching at Princeton. I was captive in the worst kind of way, because this belligerently confident, hyper-evangelical classmate preached his “sample sermon” before the students in the homiletics class.

His sermon was a lot.

Throughout the entire twenty minute sermon our homiletics professor, Dr. James Kay, looked restless and irritated. And once the sermon was finally over Dr. Kay looked exasperated. It was not the reaction the beaming student preacher had anticipated. The professor was an amateur boxer and he appeared suddenly like he was squaring up against an opponent.

“Do you realize,” Dr. Kay thundered with genuine offense, “not one of your sentences had God as their subject!”

The point seemed lost on the preacher.

“God was not the subject of any of the verbs in your sermon,” he explained. “If the word works what it says, if the preaching of the word of God is the word of God, then you don’t need any “I’s” in your sermon. The Lord is the subject of every sermon. Let the Living Word have its way with you.”

It was a mic drop moment before mic drops were memes.

Though seldom do I practice what Dr. Kay preached that afternoon— here I am, caught in the act, telling one of my stories— I’ve never forgotten the lesson.

I felt liberated to hear that there need not be any I’s in the sermon (my stories, my spiritual experiences, my religious insights, my— God forbid— advice) in the sermon— not if the Living God is a God determined to reveal himself, at work through his word to bring us to himself.

The Lord is the subject of every sermon.

Let the Living Word have its way with you.

The reason we must be diligent about keeping the main thing the main thing in the church is because the good news is that you are not the good news. I am not the good news. Neither Joe Biden nor Donald J. Trump are the good news.

Jesus Christ is the good news.

The Lord Jesus is not dead.

And he is up to something in the world.

The grammar of the gospel is essential.

We are the objects the Lord acts upon.

Arguably there is no better passage of scripture to buttress Professor Kay’s point than the story of Elijah. The Book of Kings is an ironic title for the narrative it tells, for Israel’s kings and the world’s power brokers are impotent bystanders to the power and purpose of the word of the Lord. Read properly, the story of Elijah is not even the story of Elijah.

The Book of Kings repeatedly refers to Elijah not as a prophet but as a Man of God, and the preposition of possession is quite literal. Yahweh is not Elijah’s copilot; Elijah is the vehicle for the Lord’s purposeful activity. In the fullness of time, when a pall of idolatry and corruption had enshrouded the promised land, the Lord plucks un-credentialed, unprepared, unqualified Elijah from obscurity in Gilead and the Lord thrusts him into Ahab’s oval office. After Elijah proclaims the word the Lord has given him— just like the Spirit flings Jesus into the desert to be tempted by the devil— God propels the prophet out into the pagan wilderness.

With the sky shut up and the fields fallow, Ahab sends soldiers to scour the land for the Man of God whose word struck like a fever into the heart of the earth. Jezebel dispatches her spies from Sidon. Even though Elijah sojourns in Jezebel’s own territory, no harm comes to him. The Lord protects him. He is the exception to the judgment that falls upon all. All of Israel suffers drought and famine. But every evening and every morning the Lord satisfies Elijah’s hunger and slakes his thirst. Just as the Lord fed Moses manna and quail, every day the Lord offers Elijah meat by means of ravens and water from the Wadi Cheri.

The Living God is the subject of all the verbs.

Once the Wadi dries up— because, by the Lord’s word, there has been no rain— the word of the Lord comes to the Man of God and hurls him to Zarephath to the house of a widow, whom the Lord has preveniently commandeered to his cause. She knows his name before he shows up.

In the Bible, widow is shorthand for bottom of the ladder, without either hope or future. Needless to say, in a pandemic of drought and famine, a widow is the least likely person to have the resources to provide for the prophet Elijah. She had less on her shelves before God’s judgment fell across the land.

The widow confides to the Man of God that, just then, she had been gathering sticks to cook for her son. Like a prisoner on death row, with only a handful of flour left and a couple of tablespoons of olive oil in the jug, this would be her last meal. “I am now gathering a couple of sticks,” she says, “so that I may go home and prepare it for myself and my son, that we may eat it, and then die.”

As the angel Gabriel to Mary, Elijah issues a command only God can command, “Do not be afraid.” Just so, for months the flour and oil are like manna in the wilderness. The Lord feeds them. The Lord shelters them from the the shut up sky and the shriveled earth. The Lord keeps them until he once again sends rain upon the earth.

God gets all the verbs.

Meanwhile—

Ahab and Jezebel, the president and first lady, are incidental to the action.

They accomplish nothing.

Kings are supposed to provide food and water. Presidents are supposed to provide stability and security. Leaders are selected to protect their people from all enemies, foreign and domestic. But Ahab is impotent in his attempts to arrest the famine. The administration’s attempts to capture Elijah are ineffectual— the prophet sneaks across the porous border. The desperate situation reveals Ahab’s government to be dysfunctional and discredited, without the ability to remedy what ails the nation. Any of Ahab’s subjects would be right to read the newspaper and despair over the future of their nation.

Unless God is the subject of verbs.

Despair is the most rational disposition in the world— nihilism is the sanest, most honest philosophic position— if God is not up to something in the world.

Shortly after he transitioned from parish ministry to university teaching, the theologian Karl Barth learned that many of his fellow faculty members at the University of Bonn in Germany had become enthusiastic members of the fledgling Nazi movement, including— especially— the professors in the department of homiletics.

Though he had taken his position on the condition that he would abstain from political activity, the Lord told Barth that students of preaching should not learn preaching from those whose preaching had been corrupted by nationalism and populism and racism and xenophobia. "How can they proclaim the gospel,” Barth asked, “when their teachers know not that Jesus is Lord?” And so a year before the Reichstag fire election ushered a different Ahab to power, Karl Barth began teaching an unofficial, uncredited, underground series of lectures on homiletics.

A book based on his students’s notes was later published under the title, The Preaching of the Gospel. In his instructions for the “actual preparation of the sermon,” Barth infamously rails against sermon introductions:

“Basically the sermon should not have an introduction…[all rhetorical strategies at the beginning of the sermon] are to be rejected in principle.”

What is the principle?

The principle that listeners can only hope to hear a word from God if God speaks.

Deus dixit.

Our only hope, Barth insisted, is that the Word is up to something in the world. “For what do introductions really involve at root?” Barth asked his students:

“Nothing other than the search for a point of contact [between the listener and the word of God]. It is believed that this little door must be opened first before it is worthwhile to bring a message…Nein! This is plain heresy…If we understand the Bible after the manner of the Reformers, we know that no such possibility for a point of contact exists. There is only one exception, the contact which is made, of course, by the miracle of God on high.”

If they’re going to hear a word from the Lord, then it’s not because you’ve prepared them to hear but because Jesus Christ has elected to speak.

So, just get on with the sermon!

In other words—

God is more than the subject of the sermon.

He is the acting subject in the sermon.

If you grasp Barth’s point, then you see it’s not really about sermon preparation at all. It’s every bit about his fellow faculty members who fell, enthralled, under the spell and spectacle of the Ahab of their day.

Barth rejected introductions and all other rhetorical devices as a way of reminding his students that no matter what was going on in the capital, no matter what the headlines said, the Lord was surely doing greater works through his word.

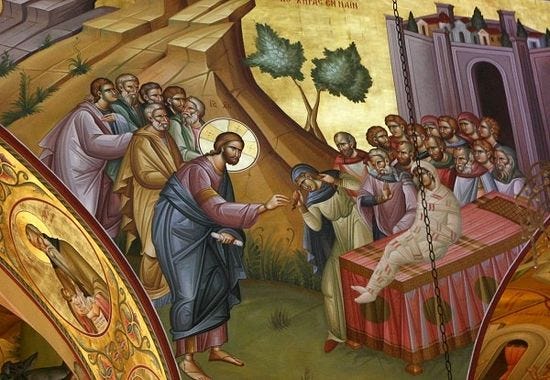

In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus enters a town called Nain. He’s followed by a great crowd. As Jesus and the crowd approach the city gate, they collide with a crowd trudging mournfully in the opposite direction out of the city. They see pallbearers carrying the body of a boy, a widow’s only son.

Death is like that in the Bible. The work of God and God’s people advances forward and then, inexorably, it collides into Death. Death, the apostle Paul writes, is always a malevolent intruder, a cohort to the Power of Sin, the Enemy. As in, the Enemy; Death in scripture is synonymous with the Prince of Lies.

Ahab may have been ineffectual, but Death is not so impotent.

After months of manna-like miracles, Death intrudes in Zarephath. Death collides against the bulwark the Lord has erected around the Man of God. From the widow who has next to nothing, the Enemy takes her boy.

The subject of the sentence.

Death gets a verb.

And we know he was a little boy because she picks him up and she carries him over to Elijah and she holds his limp body out to the prophet as evidence of her indictment, “What have you against me, O man of God? You have come to me to bring my sin to remembrance, and to cause the death of my son!” The widow thinks her proximity to the Man of God has brought under divine inspection.

Your God has done this to him because of me, my sin!

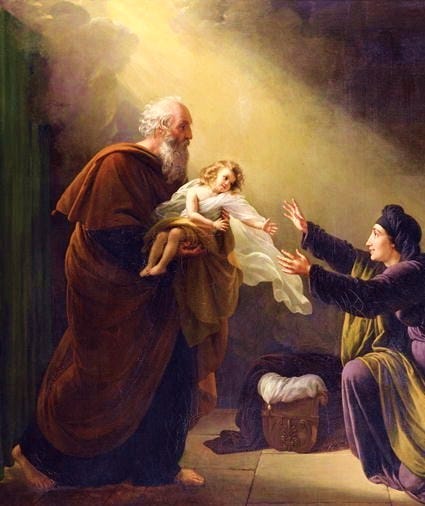

With the same audacity he displayed in Ahab’s council chamber, Elijah responds. He takes the boy from her bosom. He carries the boy up to the upper room. He lays him on the bed.

And the prophet prays to the Lord who has rested on his lips.

In the midst of his prayer, the Man of God offers an odd act. Mind you— corpses are intensely clean; they are contagious with their uncleanness. But the righteous Man of God stretches out his body to cover completely the unclean body of the dead boy.

Three times he does it.

Almost like Jesus covering you completely.

Covering your sin with his permanent, perfect record.

With water and the Spirit.

Three times.

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

The Man of God covers the unclean corpse with himself.

And then, as simply as Jesus says to Jairus’s dead daughter (“Talitha cumi”), Elijah says the widow, “Your son lives.”

In the second century, a theologian named Marcion contended that the God of the Old Testament could not possibly be the Father of the Lord Jesus Christ. Though Marcionism was promptly dismissed as a heresy, it has stubbornly abided in the church like a weed. In all likelihood, you have watered that weed at some point with your words.

Marcion was condemned in part because of the straightforward reading of passages like this one in the Old Testament. Quite obviously, the Word who arrests Elijah’s life and rests on Elijah’s lips is the same Word who overshadows Mary’s belly. This passage is the gospel before the Gospels. The Word commandeers Elijah and crosses the boundary into the wilderness— just like Jesus. The Word hijacks Elijah and crosses the boundary into territory held by the Enemy— just like Jesus. The Word covers over uncleanness with his own body and crosses the boundary into Death to bring a sinner back— just like the Lord Jesus Christ.

The Word of the Lord who comes to Elijah is Jesus.

And this should not surprise us.

Fact is:

Jesus never meets a corpse that does not rise.

The widow of Nain’s son.

Jairus’s daughter.

Mary’s and Martha’s brother, Lazarus.

And here in Zarephath.

Of course, the widow’s boy rises from the dead.

The word of the Lord on Elijah’s lips when he prays over him is Jesus.

They all rise from the dead.

The widow’s son, Lazarus, Jairus’s girl, Nain’s son— they all rise not because Jesus does a number on them, not because he puts some magical resurrection machinery into gear, but simply because Jesus has that effect on Death.

They rise because he is Resurrection.

He is both subject and verb.

Meanwhile, King Ahab— Elijah is safe, Elijah is fed. Elijah has saved a son from death— is utterly absent from the drama.

Which is to say, you can be so preoccupied with presidents and politics that you miss the power of God at work in the world.

During the pandemic, I paid a pastoral call to an eighty something man from the neighborhood who called the church office worried that “when the virus finally gets here, I’m exactly the kind of geezer who will have a bad go of it.”

He asked me to come visit him and “do more than shoot the breeze.”

While he made instant coffee, I looked at the flag he had hung on the wall, folded and framed in a wooden triangle. Photographs of a younger man surrounded it. I started to ask him a question but he waved me off. He had something he wanted to get off his wheezing chest.

He was a Vietnam vet, he told me. The cancer that was killing him slowly likely came from the Agent Orange that killed others. Then he corrected himself, “That I killed others with.”

I nodded.

He handed me a mug of Folgers and gestured for me to sit down.

“It’s been weighing on me for a while,” he said, “but then when this plague struck, I thought I shouldn’t waste any more time.”

I took a sip and looked at him, unsure where this was headed.

“I want to confess, I guess” he told me staring at the steam coming off his coffee, “what I had to do in the war— it was necessary, maybe, but it was still sin.”

And so he confessed.

Before he was done, he was weeping like a widow.

I put my mug down on the coffee table. I stood up from the recliner. I made the sign of the cross on his forehead and I said, “Vince, in the name of Jesus Christ and by his authority alone, I declare unto you the entire forgiveness of all your sins.”

I waited until his eyes were dry before I stood up to leave.

He had been dead in his sins.

In the middle of a pandemic, with the nation bitterly divided over who would sit in Ahab’s Oval Office, God had just raised the dead to new life.

By grace.

Notice—

The widow of Zarephath believed in God. She had been on the receiving end of a manna-like miracle for months. But she didn’t know God. She didn’t know God is a God of grace. When Death collides with her life, she assumes the Lord has slain her son to punish her for her sins.

Your God has done this to him because of me, my sin!

Notice too—

Elijah has no reply for her. He doesn’t know whether God has taken her child as a punishment for sin. He asks that very question in the first part of his prayer. Elijah doesn’t yet know God is a God of grace. It’s as though the only way you can be certain of God’s grace— the only way you can truly know God and God’s heart and God’s character— is if you have witnessed the Lord raise the dead to new life.

In other words, you need an empty tomb.

“Grace, grace, grace. I get it,” a listener griped to me after I had preached here for about year, “I get it. When are you going to move on and preach a different message?”

“I’ll stop preaching grace,” I said, “when you actually start believing it.”

“I do believe it!” She said, “It’s not that hard to understand!”

Really? Bless your heart.

Four years later— last February— she braced me in the fellowship hall, wanting to know my take on the alleged awakening that was sweeping Asbury University in Kentucky. What had begun as an ordinary Wednesday morning chapel service at a small college, far away from any place important with far more urgent matters going on around the world, turned into a multiweek Outpouring of the Holy Spirit that drew young people from hundreds of other colleges and universities, some from as far away as Japan and Russia.

“You don’t really believe that’s a revival, do you?! You don’t really think the Holy Spirit is responsible for whatever has swept over those kids, do you?!”

I stammered that I wasn’t sure, that I didn’t know enough about it, that I’d have to learn more.

She shook her head, as dissatisfied as she was certain:

“At Asbury of all places? You really think the Holy Spirit would work a miracle at Asbury? Don’t you know Asbury’s politics? It’s in the reddest of red states! Asbury is one of the main antagonists in the fight in the United Methodist Church. They’re not even real Methodists— they’re evangelicals. They’re for Trump. They’re against inclusion. They’re the bad guys as far as I’m concerned. There’s no way God would work a miracle among them.”

“Well,” I said, “Now that you’ve put it like that I guess I’d say, ‘Yes, that sounds exactly like something a gracious God would do.’”

After he’s tempted in the wilderness, Jesus preaches his first sermon. For his hometown synagogue, Jesus preaches from the Book of Isaiah. Once Jesus finishes the sermon, the congregation immediately “spoke well of him and marveled at his gracious words.” That Jesus was from Nazareth they took as a sign that God was on their side.

So Jesus grumbles, “Doubtless…you will demand that I do here in my hometown for you what you have heard I did in Capernaum.”

Right then the self-satisfaction starts to disappear from their faces. And just before they’re filled with wrath and try to kill Jesus— try to throw him off a cliff— Jesus preaches grace one more time.

“Remember,” Jesus says, “there were many widows in Israel in the days of Elijah. It didn’t rain for three and a half years— famine gripped the whole land. There were many widows in Israel in those days. And there were many mothers with dead children. And what did God do? Did Yahweh send Elijah to a single one of those Jewish widows in need? Did God raise any of their starved children from the dead? Did the God of Israel roll up his sleeves and show up for the people whose side he was supposed to be on? Elijah was sent nowhere else but to Zarephath in the pagan land of Sidon, to a gentile widow outside the promised land.”

They hated the message of grace so much they tried to kill him.

But Jesus got the grammar straight.

Elijah was sent.

It’s passive voice, but flip it around and God is the subject of the verb.

So come to the table.

The Risen Christ is the host.

He invites you.

He wants to give himself to you.

It’s easy to miss if you’re looking in the wrong places.

It’s easy to miss if you’re preoccupied with the wrong people and powers.

The Lord is at work in the world.

Here.

Share this post