Genesis 27.1-13

“Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself,” the prophet Isaiah exclaims to the Lord at the end of a long ecstatic utterance.

“Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself.”

In the Gospel of Luke some listeners interrupt Jesus’s lesson plan. He was just about to teach them the parable of the barren fig tree. They interrupt and ask him if he’d seen the news trending on Twitter. “Did you hear Jesus?” they ask, “Pontius Pilate killed a whole church full of Galileans. He had them struck down while they were in the middle of worshipping the God of Israel according to God’s law.”

Luke doesn’t report the rest of their questions. Luke needs not.

We can hear the questions in our own voices. Why? Why do bad things happen to (sinful) people? Where? Where was God when members of his flock were slaughtered like sheep? How? How do you explain this tragedy, Jesus? Was God punishing them? Is the Almighty an underachieving pretender? Is there a reason it happened?

Is there a will which willed it?

We desperately want Jesus to say, “No, shit happens.”

But the Lord Jesus doesn’t say “Yes” or “No.” He instead answers in a manner that certainly would bar him from ordination in the United Methodist Church. The Lord Jesus replies, “No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish.”

God’s gonna do the same to you unless you repent.

That’s not a “No.”Nor is it a “Yes.”

“Those Galileans weren’t any worse sinners than the lot of you; God’s gonna do likewise to you unless you repent.”And then Jesus points to another news story on his Twitter feed.

“What about the eighteen folks who perished when the tower in Siloam collapsed. You think they were especially rotten in a manner different from you? Of course not, but I’ll tell you what. Unless you repent, God’s gonna do the same to you.”

In the Gospel of John, the disciples ask Jesus about a man born blind.“Rabbi, who sinned? This man or his parents that he was born blind?”And Jesus very helpfully refuses to accept the premise that the man’s blindness has anything to do with anyone’s sinfulness. But Jesus rejects the premise for reasons that are even more offensive to our enlightened sensibilities than the original premise. Jesus says God made the blind man blind. God made him blind; so that, the work of God might be revealed in him. Again, Jesus would never get past the United Methodist Board of Ordained Ministry.

There are two conclusions we can draw from these responses by the Lord Jesus, one comforting and the other unsettling.

The Lord Jesus forbids us from conjecturing any causality between a person’s sinfulness and the suffering that besets them. Jesus won’t allow us to say this thing is happening to them because of that thing they did.

The Lord Jesus believes— and so we are compelled to believe— that there is a will that wills in the world, often in ways that shock and offend us.

“Unless you repent, God’s gonna do the same to you.”

Such a God appears even more mysterious when we insist on saying that such a God is one and the same with the Jesus who speaks of him.

“I am the Lord,” God declares to the prophet Isaiah in that same passage, “I make weal and create woe.”

And the prophet replies, “Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself.”

And the Lord does NOT correct him.

Notice—

It’s not, “Truly, thou art a hidden God,” as though the matter was God’s distance from us or our perception of him.

It’s not that God is hidden. It’s not an adjective. It’s a verb. God hides. God hides himself.

God is the hidden Lord of his own unhiding, says St. Gregory.

At the start of Advent, Maria Kamianetska mailed a photograph to her husband who had remained behind in their home village in Ukraine.

She attached a note, “You have a son.” In the picture, baby Serhii’s eyes were closed. On his head sat a little white hat. His tiny body was swaddled in a matching blanket. Maria gave birth to him in a city maternity ward in a region of Ukraine allegedly annexed by Vladimir Putin’s army.

After nine months of carrying her baby through a war zone, Serhii had come into the world at a healthy six pounds with three siblings anxious to meet him. They never did. After nursing him and lulling him to sleep and laying him in the crib next to her bedside, a Russian rocket crashed through the maternity hospital. Like that tower in Siloam, the maternity ward’s walls collapsed with everyone inside.

Serhii is the youngest casualty of Putin’s invasion. He did not live long enough to be issued a birth certificate. All of the nearly five hundred other children killed in the war thus far have been older than Serhii. Serhii was so young and so tiny that rescue workers picking through the rubble at first mistook him for a doll.

“That’s my son!? Maria, his mother, had shrieked.

Fifteen attended baby Serhii’s burial. Shelling rumbled in the distance of the cemetery as the priest placed a cross bigger than the baby into the casket and prayed the commendation.

Serhii’s siblings didn’t attend the burial. They knew their new baby brother wasn’t coming home after all but they did not know why. Because neither Maria nor her husband knew how to explain Serhii’s death to them.

Because, after all, what is there to say except, ““Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself.”

The hiddenness of God—

It’s more than an unmistakable fact of human experience. It isn’t merely a feature of the Book of Isaiah. It’s Christian dogma. As much as the doctrine of the incarnation or justification through faith alone, the hiddenness of God is one of the constructions with which we speak Christian. The contemporary American theologian, Robert Jenson, writes that when he first encountered the dogma as a young student, he said to himself,

“THIS about God’s impenetrable hiddenness is really great stuff! And, moreover, it surely must somehow be true.”

But the dogma doesn’t assert quite what you assume.

God’s hiddenness does not name his metaphysical distance from us. Quite the opposite, the belief speaks to the problem of the character of God’s presence with us. If God were far off in some metaphysical distance, a cosmic butler in the great by-and-by, then we could exonerate God from the troubles and tragedies that befall our history.

But such a distant God is not the God of the Bible.

Such an aloof, hands-off God is not the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ nor is it their Holy Spirit who blows where the Spirit wills to blow. If God rules as his creation’s here and now Lord, if Jesus Christ sits at the right hand of the Father, then baby Serhii not only sits on his ledger waiting to be to be accounted but baby Serhii also masks God’s visage. Baby Serhii is an instance of God’s hiding.

“Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself.”

The prophet Isaiah utters that confession upon hearing God announce that God would use a pagan emperor, Cyrus, to deliver Israel from the exile into which God himself had originally sent them.

“God works in mysterious ways his wonders to perform,” sings the hymn. William Cowper, the hymn writer, suffered from lifelong suicidal depression. He knew of what he sang.

“Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself.”

That God hides does not mean that God is only vaguely glimpsed.

You can’t put God in a box, some say. Never mind that God, having already put himself in tent and temple, placed himself in a space no bigger than Mary’s womb. The hiddenness of God does not mean we know God only partially. No, Jesus is the fullness of God. There is no knowability of God yet to be discovered that lies beyond Jesus. That God hides does not mean that God is not glimpse-able.

The hiddenness of God instead refers to the impenetrability of God’s moral agency.

The hiddenness of God marks the boundary beyond which we cannot discern a good or moral pattern to God’s providence.

God is good (all the time), we profess. But, with scripture, we cannot say how. We cannot always— or even, often— say how God is good. This is what St. Paul is after when he cites Job and Isaiah and asks, “God’s ways are unsearchable…who has known the mind of the Lord?”

The way God is God seems to us morally problematic.

That’s what the dogma claims.

Throughout scripture, the hiddenness of God does not refer to the weakness of our knowledge or absolute uniqueness of God. It refers to God’s reality as a moral agent involved with other agents. It refers to God’s history with us. As Martin Luther once said,

“If we observe how God rules history and judge by any standard known to us, we must conclude that either God is wicked or God is not.”

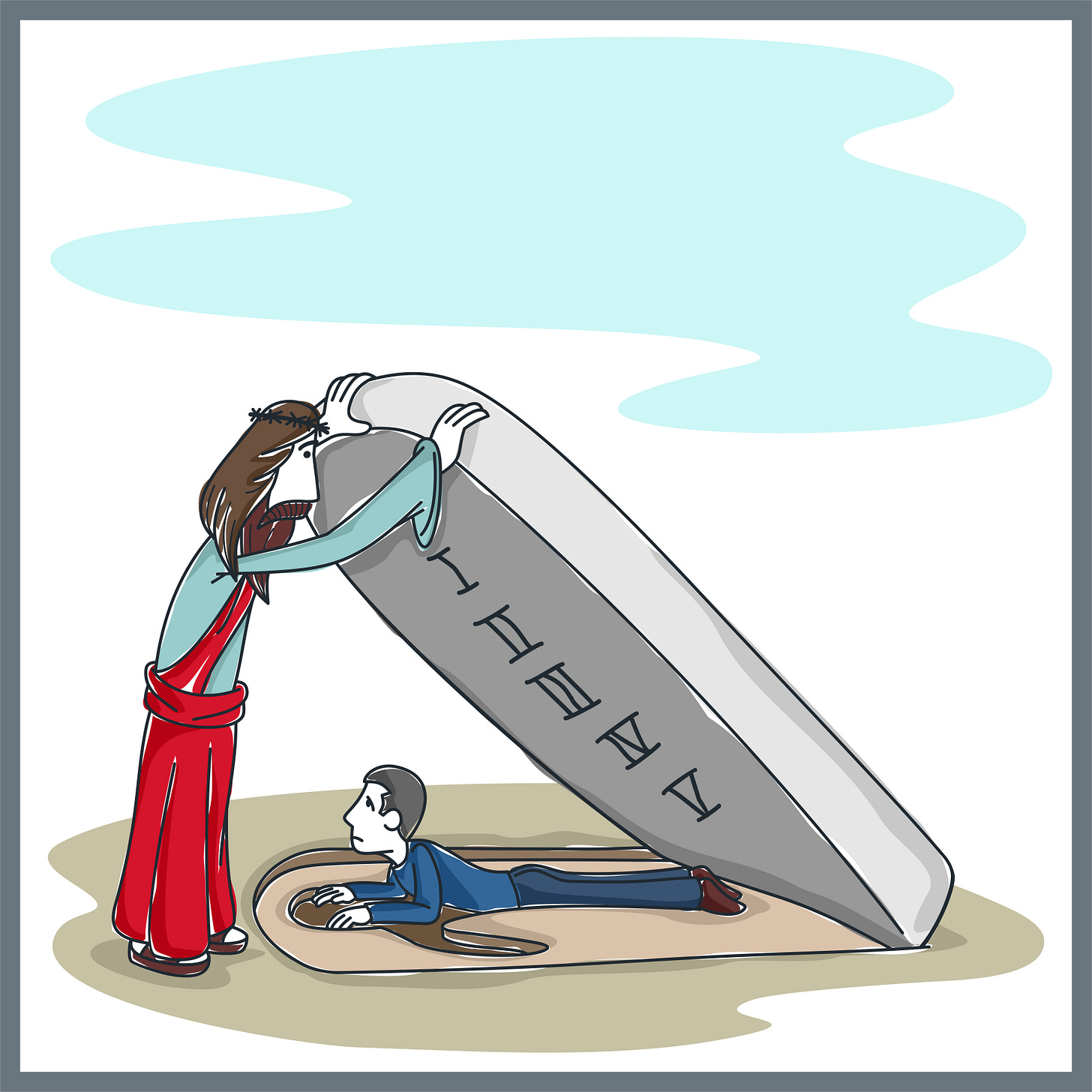

Consider, for example, the continuing story of God’s promise in Genesis 27.

Isaac and Rebekah’s marriage is the only monogamous marriage in the entirety of the Book of Genesis, yet obedience to God’s promise (“The elder shall serve the younger…”) tears it apart. So much so, notice, Isaac and Rebekah never appear on stage together. Neither do Jacob and Esau.

We remember this story as Jacob cheating his brother out of his inheritance but that’s not the case. It’s Rebekah cheating her son by means of her other son. Jacob is a reluctant co-conspirator, “Look, my brother Esau is a hairy man, and I am a man of smooth skin. Perhaps my father will feel me, and I shall seem to be mocking him, and bring a curse on myself and not a blessing.”

And already in the narrative, Jacob and Esau are not young men.

They’re seventy-seven years old. Esau has two wives and children and grandchildren, all of whom are dispossessed by Rebekah’s deception of her husband.

The plot ends with the family ruptured and the cheated brother vowing to kill his twin.

Jewish and Christian interpreters alike have sought explanations to justify the theft and dishonor Rebekah and Jacob commit. Esau was a hypocrite, they speculate, he didn’t truly love his father. He loved his father for the prospect of his father’s wealth. Jacob was the virtuous, obedient child, they say, he gets the inheritance because he was the deserving one.

But none of that is in the text.

The text isn’t even really about them; it doesn’t tell us anything about their motives or character. The text is straightforwardly about God and God’s promise. The text is about the continuing forward of the promise, and the consequence of its continuance in this instance is a broken family and a vow of blood vengeance.

The tradition of squeamish interpretation aside, quite simply:

Esau is cheated.

All is house is disinherited.

Isaac is dishonored.

Jacob is exiled.

And Rebekah bears the curse of his transgression.

All because…this is the will of God.

“Truly, thou art a God who hides thyself.”

It isn’t simply that God is involved in the messiness of our history.

God is, in some way we cannot comprehend, complicit in it and responsible for it. This is simply the flip side, the God side, of the doctrine of justification by grace alone through faith. You are justified apart from any of your works, which means God justifies you by his will alone. It’s a strict implication of the doctrine of justification that whatever happens happens by God’s will— even those things we freely choose. God wills not what we freely choose but God wills that we freely choose.

Several years ago, shortly before his death, the theologian Robert Jenson agreed to be a guest on my podcast, and during the course of the interview he spoke about the hidden God:

“For example, when asked why some are healed and some are not, I answer because that is the will of the Lord. You know that I have Parkinson’s disease. Now that is degenerative disease. So that isn’t reversible. Nevertheless, I pray to be healed and one has to live with that. As to why there is so much suffering in the world, such evil, that’s the famous theodicy question, and in my judgment it’s the only good reason not to believe in God. To say despite all the suffering in theworld, all the suffering in our lives, God is good: that’s as far as can go and no further.”

When I was a college student, I often worshipped at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. It was just off grounds so I could walk easily. Even better, St. Paul’s had a 5:30 service on Sunday afternoons, which fit nicely with Saturday nights.

I remember one Sunday during Lent. This lady was in front of me in the receiving line after worship. She looked to be in her fifties. I could tell just from her bearing that she was righteously livid. Her white hair was tightly braided. She wore wire glasses and plain slacks and a shirt that smelled of grass clippings. She poked the priest in the chest when he offered her his hand.

“How dare you!?” she exploded.

He looked genuinely flummoxed.

Unspoken words fell stillborn from his lips.

“How dare you take the word and the absolution away from us.”

Then I knew as quickly as the priest what she meant. For the season of Lent that year, the church had replaced— I kid you not— the scriptures with readings from Robert Frost’s poetry and they had decided to “put away the absolution” until Easter so that there was only confession of sin but no forgiveness.

“How dare you take those away,” she hollered in the way of someone who hasn’t yet realized they’re hard of hearing.

“I’m a social worker. Do you have any idea the hell I wade through every day? Just yesterday I was with a child with cigarette burns all over his body. You can probably guess who put them there. And Wednesday it was a mother too strung out to bother noticing her baby was malnourished. Most of my every days it’s like God’s nowhere to be seen. Don’t you dare take away two of the places he’s promised to be found.”

And the priest just nodded with an awkward smile like this was a worship planning suggestion. But she just stood there, as immovably determined as Rebekah before Jacob.

“Well,” she said.

“Well, what?” the priest asked.

“You need to absolve me,” she said, “In fact, you need to announce the forgiveness of sins to all of us. I’m not moving until you do.”

And she held out her arms like she was holding back a flood.

The red-faced pastor made the sign of the cross in the air and said, “In the name of Jesus Christ, your sins are forgiven.”

The line of folks behind me in line mumbled in reply, “In the name of Jesus Christ, your sins are forgiven.”

“Maybe I ought to go to law school,” I thought to myself.

The world is constituted by worse than deception. All due respect to Dr. King, the arc of the moral universe does not, on its own, bend toward justice. Everyone knows, firsthand even, the hiddenness of God. It’s a very shallow faith that has not wrestled with the fact of the hidden God.

If God can be judged by any standard known to us, we must conclude that either God is wicked or God is not.

Everyone knows God hides. Only Israel, only the Church, know that the self-hiding God can nevertheless be found in creaturely means like the word that absolves, the water that washes and the bread that is the God of the Passover’s own body. God hides, the dogma insists; so that, God may be found only in the promises through which he gives himself to us.

To say that Abraham and Jacob and Rebekah were justified on account of their faith in God’s promise— that doesn’t go far enough.

The claim is really that the Lord wants to be known and related to in no other way but faith.

Why?

Because, just like everyone else in your life, God doesn’t want to be used. That is, after all, the essence of idolatry.

God doesn’t want to be used. And we are not neutral seekers of God’s majesties. God doesn’t want to be used. Like any other person in your life— and God is a person— God doesn’t want to be used. God wants to be trusted. And loved. And so God hides. In every way. Except in the places where he’s promised we will find him. In a word that says, “I will raise you from the dead.” In water that says, “You are mine.” In wine and bread that says, “You’re wondering where I am for you. I’m here, as near to you as your lips and your belly.”

Still, the fact that the God who hides has promised he can be found in, say, bread or the absolving word does not absolve God of, say, baby Serhii or whatever dread and suffering looms over you. If God is the buck-stopping will of history, then the buck stops with him. We’re still left with this apparent split in God’s image:

“This is my body, broken for you.”

“God’s gonna do likewise to you, unless you repent.”

The God who is the absoluteness of the gospel promise is pure love.

The will behind all events is not so easily apprehended as pure love or even as pure justice.

What do we do about this apparent split in God’s image?

If God wants to be known and related to on no other basis than faith, then we have no other recourse but to abstain, abstain from any attempt to reconcile the apparent contradiction.

On the one hand, we admit that God is the ambiguous will behind all events, good and evil— that there is a will behind all events the gospel compels us to affirm.

On the other hand, we hear and trust the gospel of God as pure and personal and universal love.

And finally, we insist that these two images nevertheless constitute one and the same God but we dare not say how.

The how is the one fundamental truth reserved for revelation on the last day, when time ends, and all the jarring and dissonant notes of history are gathered together in God’s great fugue called creation.

What do we do with the hidden God? We abstain from any attempt to reconcile him with the crucified God. We admit God is the ambiguous will behind all events. And we trust the God of the gospel. But we abstain from saying how they are one and the same God.

The missing how is the darkness.

According to the Washington Post, it was cold the day they buried baby Serhii so Maria, baby Serhii’s mother, bundled up in a black winter puffer coat. On the back of the black jacket were the words,

“Everything will be fine. It will be even better every day.”

The words seemed to be an absurd contradiction to the artillery shelling that could be heard in the distance from the cemetery and the tiny coffin being lowered into the earth. But Maria’s black jacket is no different than what we do when we take bread, break it, acknowledge a world that would crucify him all over again, yet nevertheless look to that day when Christ will come back in final victory.

Faith trusts that, on that day, on the last day, in The End, God will all have told with his history with us not only a coherent story but a good one.

“To say despite all the suffering in the world, all the suffering in our lives, God is good: that’s as far as can go and no further.” Actually, we can go a bit further. We can come to the table.

Share this post