Revelation 7.9-17

Neil was a high school baseball player whose life ended in the early innings, leaving his family and friends like hometown fans wondering how the late innings might have gone if the storm had not come.

Shortly after he graduated high school, Neil taught eleven year old boys basketball such was his joy for the game and passion to pass it on to others. And such was his father’s love of Neil that Mike would sit in the uncomfortable bleachers and watch eleven year old boys play ball— not because he had any grandsons in the game but because the father wanted to watch his son mentoring other fathers’s sons. “From up in the basketball bleachers,” Mike told me in planning his son’s funeral, “that was the perfect spot to see Neil at his best and his most alive. The bleachers were the best spot to see Neil’s passion and joy and kindness and patience and potential.”

Life off the court came harder for Neil.

The camaraderie he found on sports teams was missing in meetings. One winter night he drove drunk to an AA meeting and hit a tree a block from his house. The cliche about drunk drivers always walking away from the scene of an accident is a lie. His parents heard the crash before the police contacted them.

His parents were not parishioners. They were not even believers. They told me so when I went to their house to discuss their son’s burial. “We’re not spiritual or religious,” Mike told me when he invited me into the foyer of their split-level, “We’ve just driven past your church for years and…” his voice trailed off and he started to cry.

“We’re not religious at all. I don’t even believe in God or Jesus or the Bible or…”

And again his voice trailed off. He did not have the stomach to say heaven.

I don’t believe in heaven or its eternity.

“We had no idea who to call so we called you.”

Mostly, they just told me about their son. They had no interest in the particulars of the funeral service, no opinions about prayers or scriptures or hymns. They were neither spiritual nor religious, Mike told me again when I asked about the liturgy. So he surprised me when, at the end of our ninety minutes together, after I stood up and closed my notebook and pulled my car keys from my pocket, he held out his finger— like he was adding a starter to his menu order— and he said, “You’re going to wear a robe, right? And a….”

He mimed the stole I wear around my neck.

“We want you to wear a robe and, you know, the getup.”

I nodded.

“Since you’re not believers, can I ask why you care what clothes I wear?”

And Neil’s Dad said to me:

“You strike me as a smart, truthful guy, but if you’re going to stand up there in church and make a promise about my boy’s future I need it— we both need it— to be more than your personal opinion. I have never believed such promises, but now I want to believe them and so we need you to look like you are not just making it up as you go along. We need you dressed as though the promise is true. We need you to dress so that we can see a whole history behind you of people who believed this too.”

We need you dressed as though the promise is true. We need you to dress so that we can see a whole history behind you of people who believed this too.”

Years ago I saw an article online about an event in Miami called the Christian Fashion Week Expo. Initially, it struck me as so ridiculous that I wrote a deadpan sarcastic blog post poking fun at the idea of Christian fashion. I included photographs of my legs in my super short Magnum P.I. shorts. The producers of the Christian Fashion Week Expo somehow stumbled across my blog post and thought it was so funny that they mailed me tickets and press credentials for the event.

“You are what you wear,” someone had written on the back of the press pass along with a smiley face in bold black ink.

Just this week I was running on the treadmill at the Rec Center. I wore a red banana as a headband, a shirt so old you could read the Washington Post through it, and gray and black shorts even shorter than my Magnum shorts. I was on my third mile when an old guy stepped onto the treadmill next to me and turned to face me. A red headband held back his curly white hair, and he too was wearing shorts barely long enough to cover the parts of him required by law. He tapped me on my shoulder. I slowed my pace and I took my out earbuds so I could hear whatever he wanted to say to me. He pointed at himself and then me and smiled at our likeness.

Then he gave me a thumbs up and shouted, “The clothes make the man”.

He was not wrong.

I came of age in the ’90’s when, inspired by Nirvana and other grunge bands, we all donned the flannel and denim uniform to display collectively our individuality and our nonconformity.

George Carlin said that he only wore plain t-shirts because he did not want to be a walking billboard for the Man. “I’m the only one whose products and opinions I can accept,” Carlin joked.

In other words, you are what you wear.

Ironically, today on Etsy alone, you can buy dozens of different t-shirts bearing George Carlin’s likeness along with one of his trademark off-color jokes.

A former parishioner of mine invited me to pray when he transitioned from his role as a state prosecutor to a district judge. He told me later that his black robe acted upon him too. “It gives me confidence,” he said, “otherwise it’s an impossible, awesome task to sit in judgment upon another human being and decide their future. I don’t think a judge can be a judge without the judge’s clothing. It signifies that I render a judgment that is not my personal preference but what the law demands.”

Stanley Hauerwas jokes that a god who refrains from telling you what to do with your pots and pans, your clothing, and your genitals is not a god worthy of your worship. In chapter seven of the Apocalypse, scripture provides us another reminder of how unspiritual are both Judaism and Christianity. Even at the End with a capital E, the Bible takes pains to point out mundane, material matters like clothes.

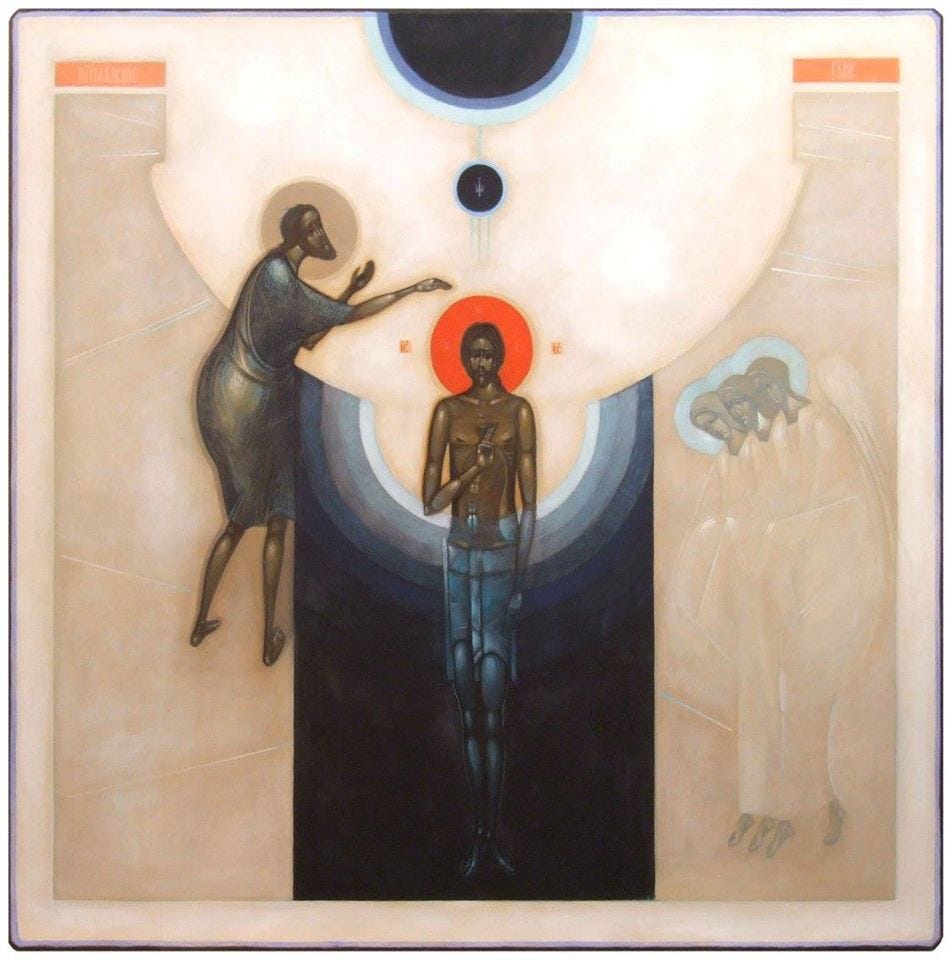

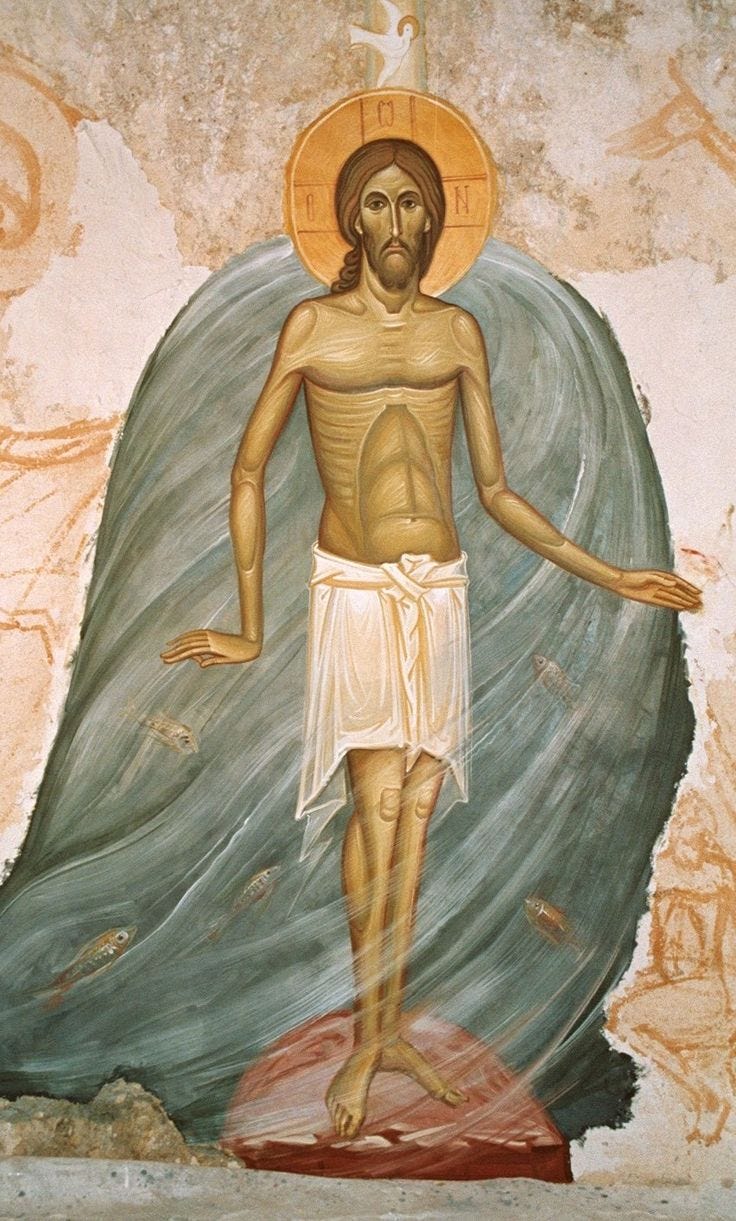

“Who are these robed in white?” one of the elders asks John the Revelator.

The Seer replies to the elder, “Sir, you are the one that knows.”

And the elder replies to the prophet, “These are they who have come out of the great ordeal; they have washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb.”

In the Fulfillment, the saints wear robes.

Robes washed in the blood of the lamb.

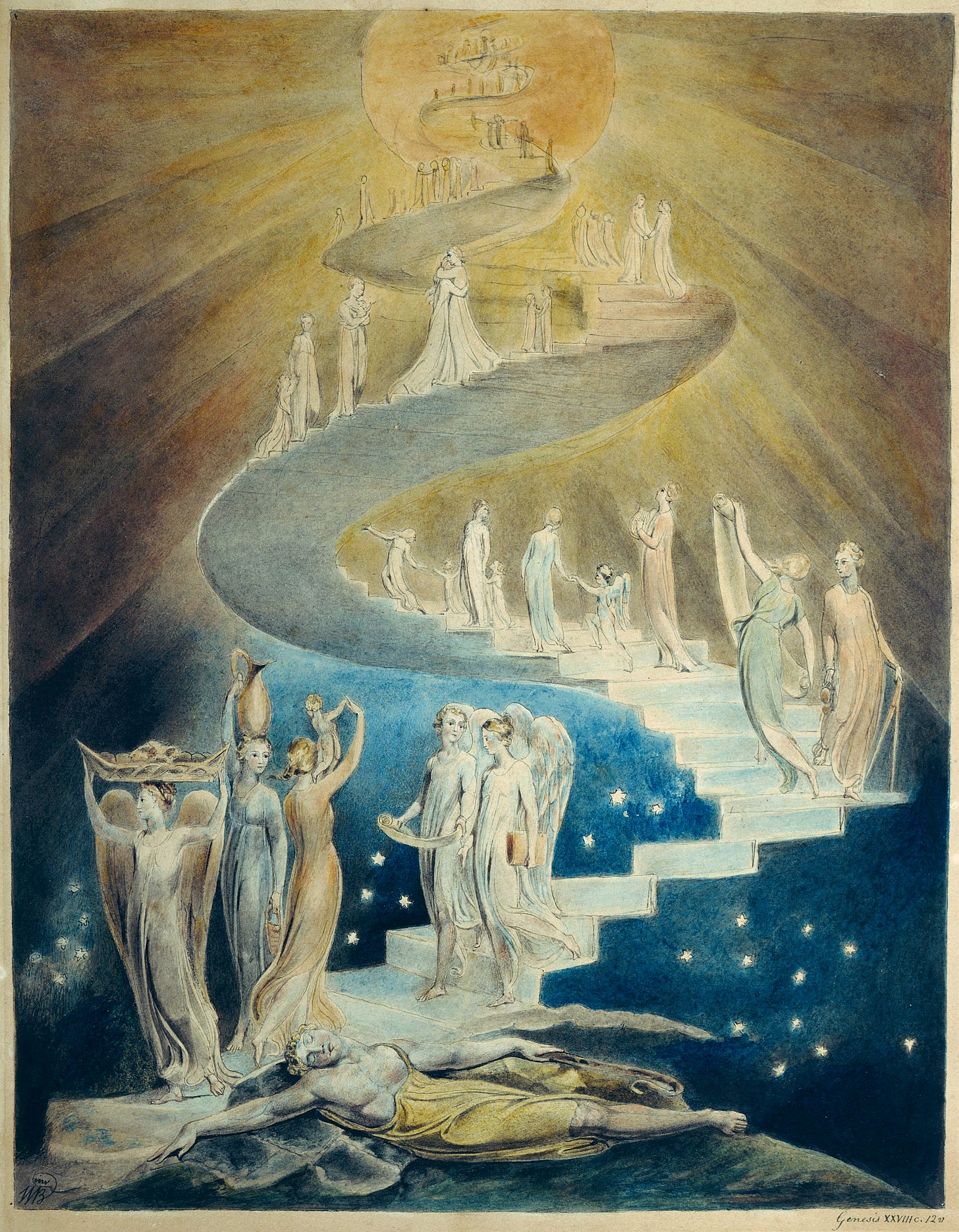

Maybe this sartorial reference in the Book of Revelation is fitting given how the story God makes with us began in the Book of Genesis.

In the beginning, you will recall, clothes were a problem. The Lord who spoke all into existence addresses the creatures Adam and Eve but thereafter they become afraid of their Creator. And afraid of God, they grow ashamed. We make garments out of leaves in order to hide our nakedness before God.

Before they exit Eden, the Creator turns to tailoring and the Lord makes Eve and Adam clothes from animal skins to protect them from elements. Thus, even on the occasion of the fall, clothes— the symbol of our original sin— become a sign of God’s benevolent, bespoke grace. No longer merely naked, Adam and Eve are clothed by God.

You are what you wear.

It’s so unspiritual.

Again and again, the Bible elaborates on attire.

The Book of Genesis ends like it began— in the closet, with the infamous coat that Israel gave to his son Joseph. Like in the garden, the garment had a double meaning. On the one hand, the coat of many colors signified Jacob’s singular love for his Joseph. On the other hand, Joseph’s prized and peculiar coat provoked his brothers’s sin.

Clothes not only make the man; clothes can make men commit terrible acts.

Over and again, scripture speaks of clothes.

The Bible speaks even of God having clothes.

Psalm 104 says, God has clothes. God is garmented in light. In Exodus 28, when Aaron is set aside to be the Lord’s first priest, Aaron is said to have holy clothes, giving him honor and holiness. The Lord’s instructions for Aaron’s garments goes on for forty verses.

The clothes make the man.

After all the twists and turns in his ministry, the prophet Isaiah declares in chapter sixty-one, “God has clothed me in a robe of holiness and a mantle of justice as a bride groom; God gave me the clothes I needed to do the job of proclaiming the truth to Israel.” Just so, scripture sees clothing— Isaiah’s clothing— as a sacrament of God’s grace; that is, a gift that makes you someone than you would otherwise be.

Neil’s father, Mike, had said to me, “I have never believed such promises, but now I want to believe them and so we need you to look like you are not just making it up as you go along. We need you dressed as though the promise is true. We need you to dress so that we can see a whole history behind you of people who believed this too.”

I was curious why two unbelievers cared so much about I wore to their son’s service of death and resurrection, but I would never have considered wearing simply my street clothes. The truth is that there are times, especially those occasions when I have to help parents bury their children, when I do not particularly feel like being a preacher or a priest.

When my faith feels as meager as a mustard seed, I need the clothes to make me more than I otherwise want to be.

You are what you wear.

It is so unspiritual, all this attention in the Bible to your pots and pans, your genitals, and your clothes.

Yet, according to the logic of scripture the sacramentality of clothing is such that to give some one your clothing is to give them your very self. In the Book of Samuel, Jonathan and David covenant with one another in deep friendship and, as an irrevocable sign of their bond, they do a peculiar thing.

They exchange their clothes.

Jonathan puts on what David was dressed in.

David puts on the clothes Jonathan came wearing.

Just so, each of them gives himself to the other.

Similarly, the prophet Elijah does not give advice to the novice Elisha.

Elijah gives Elisha an item from his wardrobe. Elijah gives his mantle to the rookie prophet. Elijah bequeathes Elisha all of his authority by giving him his clothes.

Uncle Ben was only partially correct. It’s not only that “With great power comes great responsibility.”

In the strange new world of the Bible, clothes come with great power.

Obviously— Batman is not Batman if Batman just looks like Bruce Wayne.

With clothes comes powers.

Sometimes I think we preachers wear these robes and all this get up not only to reassure you, but to reassure ourselves, to give us enough courage to get up and commit such a crazy bold act as to speak for God.

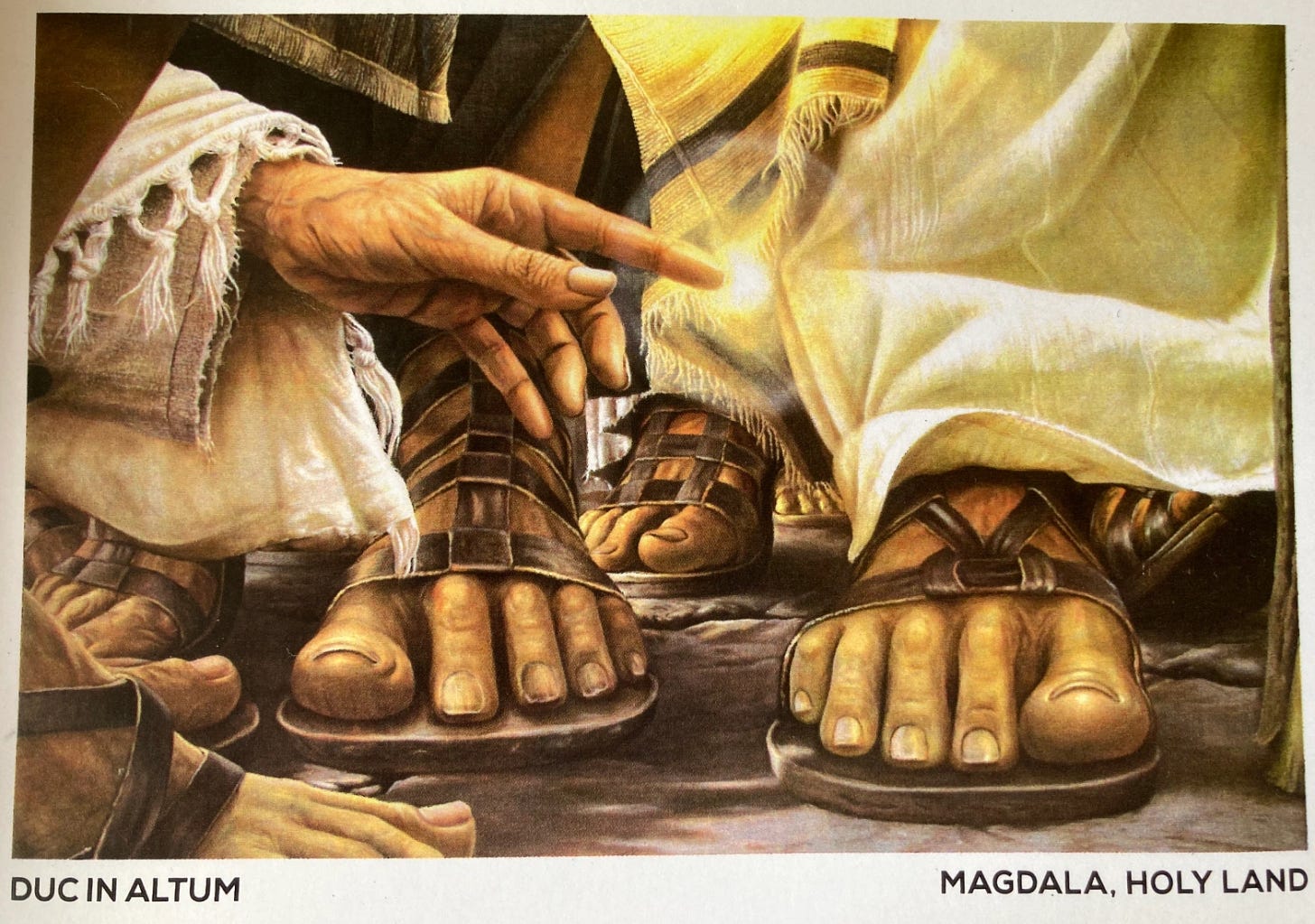

According to the Gospels, Jesus’s own clothes— not just Jesus, his garments— possessed power. The woman in Mark 5 said, “If I could just touch the hem of his robe, I can be healed.”

Admittedly, it’s an embarrassing notion, “If I could just touch his clothes, they’ll heal me.”

But then, she was.

Healed.

With clothes comes power.

When the prodigal son returns home, what does his father give him?

Not a lecture and a wag-of-the-finger. Not a summons to straighten up and fly right or threat about no more second chances. Not a bed in the hired hands’s bunkhouse.

Rather, the father says to those hired hands, “Fetch me a robe and bring me a ring and get me some shoes and put them on his feet.” In other words, clothe this prodigal son of mine like royalty. To the son who had wished his father dead and set off for the far country, the waiting father symbolically gives him everything he's got— all over again.

The prodigal father knew what the comedian George Carlin knew, what the Bible teaches from front to back, clothes show forth our deepest identity and our commitments.

Come to think of it, maybe the producers of the Christian Fashion Week Expo knew more than this pastor knew a decade ago. Clothing, scripture insists, is never just a matter of covering our bodies from indecency or the elements, a utilitarian necessity.

In the Bible, clothing is reality.

You can change a person.

You can transform a person.

You can make a person a whole new person.

Simply by the clothes you put on them.

Thus to refuse new clothes is to reject a new identity…

Jesus tells a parable about a king who throws a wedding party for his son. But really, it’s a parable about a guy who refuses to change his clothes, refuses to accept a new self.

An evite goes out, but those in the VIP queue—the fat cats and country club set, the season ticket holders and the keto dieters, the cronies of the rich man—mark the invitation read and forget all about it.

So the rich man says, “Hey, I’ve already paid the photographer. I’ve got a Costco’s worth of beef tenderloin under the broiler, and the DJ’s already started playing the Electric Slide. Go out beyond the suburbs and bring in the folks from the Halfway House—and don’t forget those guys who loiter around the 7-Eleven too. Let them come into my party. The 1 percent don’t deserve my generosity.”

But then, Jesus says, among the good and bad gathered into the king’s party, this panhandling vagrant makes it past the maître d’ only to get himself shipped off to a place worse than Cleveland all because of the way he’s dressed.

“You there—yeah you.”

Actually, the word the king uses in Greek is hetaire, which means, basically, “Buster.”

“Hey buster, how’d you get in here dressed like that? We’ve got beluga on ice and Chateau Branaire-Ducru uncorked. This party is black tie and tails only.”

“Well, sir, I was sleeping outside next to the trash bins only an hour ago.”

And the “gracious” king responds, “Really? Well then...Bind him, hand and foot! Throw him into the outer darkness where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth!”

To show up to the wedding feast of the king’s son without the proper garment, Jesus says, it’s more than a party foul.

It’s a permanent sort of problem.

“Bind him, hand and foot! Throw him into the outer darkness where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth!”

Jesus’s parable in the Gospels is an important parable to recall when it comes to the Book of Revelation because all the action and imagery of the Apocalypse to John is building to what the company of heaven calls the marriage supper of the lamb.

Only those wearing the proper garment get in, Jesus says.

Neil’s father, Mike, had insisted to me that they were neither spiritual nor religious. They did not believe, he shook his head at me in their foyer. They did not believe in God or Jesus or the Bible or any promise of eternity vowed therein.

Nevertheless, I found out on my way out of their home that Neil’s mother and father had gotten Neil baptized when he was just a baby. Almost as an afterthought, I was telling them where to meet me in the church on the day of the funeral. And Neil’s mother interrupted me, “We know the place. We’ve been there. We had Neil baptized there when he was three months old.”

Neil’s mother and father described his baptism as “going through the motions.”

But Christians— we are bold enough to call it predestination.

At Neil’s service of death and resurrection, therefore, I pointed back to that morning of his baptism and the promise conveyed to him in the water:

“Pour out your Holy Spirit, Lord, to bless this gift of water and he who receives it, to wash away his sin and clothe him in Christ’s righteousness; so that, dying and rising in the waters of baptism, he may share in Christ’s final victory.”

“Nothing Neil did can undo what God did that morning,” I said to the gathered grievers, “with water and the Spirit, God clothed him in Christ’s righteousness— Christ’s permanent perfect record. Whether any of us could see it on a regular basis or not, no matter what uniform Neil wore from one sport to the next, he was always wearing Jesus’s enoughness. From the day of his baptism forward, Neil lived this life just as he entered the next one, wearing an irremovable suit of forgiveness.”

Only a few people at the funeral knew that I was plagiarizing the apostle Paul when he writes to the churches in Galatia that everyone who is baptized into Christ Jesus our Lord has “put on Christ.”

Jesus as garment.

For Paul— and so, for the scriptures— a Christian is someone who’s changed clothes.

“We believe,” the Nicene Creed goads us into accepting, “in one baptism for the forgiveness of sins.”

That is, baptism saves.

Baptism is a permanent wardrobe change.

Baptism is the event whereby the carpenter’s son becomes a tailor, clothing us, once and for all, with a forgiveness woven for us by his death and resurrection.

It’s no wonder, then, that the ancient church referred to the grace of baptism as habitual grace, from a nun’s habit because we wear it, all our lives long, as an irremovable vestment of forgiveness.

“Who are these robed in white?” one of the elders asks John the Revelator.

This vision of the saints wearing Jesus Christ— it comes as one of several interludes that interrupts the flow of the Apocalypse. This particular interlude comes in between the unsealing of the penultimate seal and the final, old-aeon-ending seal.

The difference between the sixth and seventh seals is the difference between the wrath the world is already enduring and the judgment not yet come.

Between the present and the future, the already and the not yet, today and tomorrow, the Seer is given this vision of those who don’t have to fret about their table assignment at the marriage supper of the lamb.

As if to say…

The days ahead will prove difficult.

And, likely, they will prove you unfaithful.

Nevertheless!

You’re dressed for the eventual occasion.

You’ve been clothed in Christ.

You’ve been baptized.

Which is good news for any of us who ever worry about being graded according to our performance in life. That those who may enter the marriage supper of the lamb are those who have been given the necessary garments is a reminder that Christianity is more something done to you than something done by you.

For any Christian who’s ever realized that you don’t always look like a Christian, certainly don’t act like a Christian, don’t often think like a Christian, this is good news of great joy.

Christianity is more something done to you than something done by you.

As obvious as bread and wine, this the good news in this text.

With water and the Spirit, you have put on Christ.

No matter your performance in life, even if you feel like you’re dressed a mess and just got pulled in, like a beggar off the street— the Bible tells me so— you’re ready to party.

So come to the table.

You’re already wearing him.

Unless you’re deaf, you already have him in these words.

So come receive him in wine and bread. And know, you are ready— no, you have been made ready— for whatever comes next.

Share this post