That Pentecost so often elides into Memorial Day strikes me as a brute but appropriate reminder. The juxtaposition makes unavoidable the difference between the two polities, church and nation, and the liturgies that make each intelligible.

For instance, I remember several years when we took our boys to the Washington Nationals Home Opener. Before the game, the entire outfield was covered, like a funeral pall on a casket, with a giant flag. The colors were processed into the ballpark with priestly soberness. Wounded warriors were welcomed out and celebrated. Jets flew overhead and anthems were sung and silence for the fallen was observed. People around me in the stands covered their hearts and many, I noticed, had tears in their eyes. And it struck me that it felt like a kind of worship service.

There was even organ music.

And an elderly curmudgeon shushed a young family, which is as close to a worship service as you can get.

Mine was no great insight because just after the silence my oldest son said to no one in particular, “That was just like church.”

If there’d been an altar call my boys, my wife and I, and the Mennonite family 3 rows up might have been the only ones left in the stands.

Just so, it was a liturgy.

We were celebrating what’s been done for us and offering in return a sacrifice of gratitude and praise. It was a liturgy in that it was forming us into being certain kinds of people who view the world through a particular story— a story occasioned with song. It was preparing us, equipping us, to respond ourselves in a certain way if and when called upon. Looking up at the scoreboard at the pictures of fallen men and women— most of whom looked like kids still— I even had tears in my eyes.

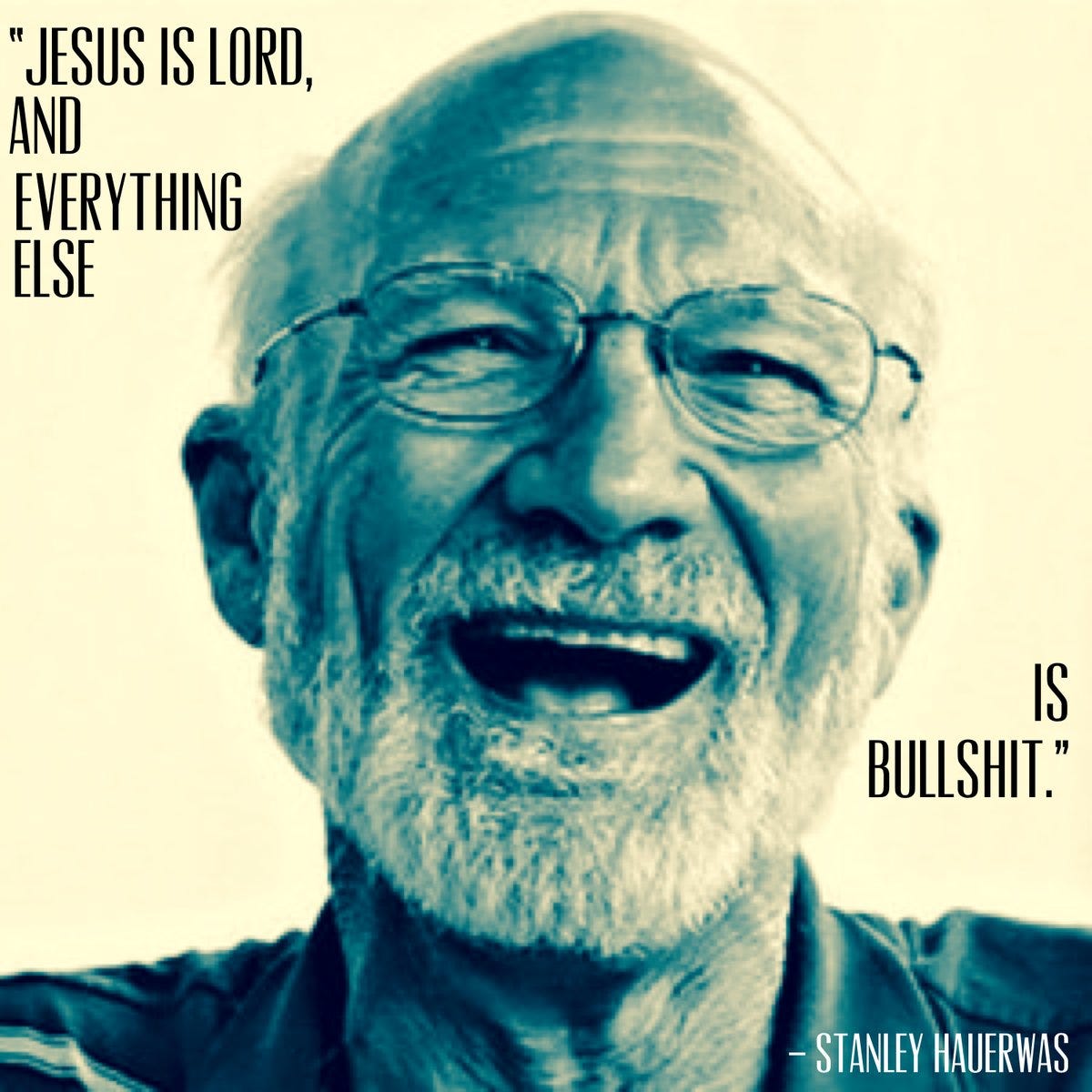

Thus, I exemplified Stanley Hauerwas’s warning that the danger posed by the presence of the American flag in Christian sanctuaries is that it’s an outward and visible sign more keenly felt than bread and wine and the Christ who hides himself there.

As Lt. Col Dave Grossman notes in his book, On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, General SLA Marshall, in his study of men combat during the second world war, observed how out of every hundred men along a line of fire, during battle, less than a fifth of the soldiers would take part by actually firing their weapons at another human being.

Over three-quarters of the soldiers would do everything they could (short of betray their comrades) not to kill.

This led General Marshall to conclude:

“The average, healthy individual has “such an inner and usually unrealized resistance to killing a fellow man that he will not of his own volition take life if it is at all possible to turn away from that responsibility.”

General Marshall’s observation is not merely a psychological insight. I believe it’s a theological insight confirmed by scripture, particularly Paul’s Letter to the Colossians.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tamed Cynic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.