Revelation 6.1-11

Based on my previous viewing history, one of our streaming services recently suggested that I would enjoy watching Stalker, a dark, dystopian science fiction film directed by Andre Tarkovsky in 1979.

Stalker is a black and white Russian language film that takes place in an unnamed country at an unspecified time, where and when there is a fiercely protected post-apocalyptic wasteland known simply as The Zone. The character called Stalker has a child whose mutations suggest the unspeakable horrors within The Zone. Stalker leads two other characters, who are cryptically named Writer and Professor, across the burnt out remains of a devastated civilization, guiding them in search of a mythical place known only as The Room.

Anyone who enters The Room, they’ve been told, will have their heart’s desires immediately fulfilled. In The Room, their dreams will come true. In The Room, you will get exactly what you truly want— not what you think you want; what you truly want.

Initially, the power of The Room sounds like a promise worth a journey. Only, when they arrive at the threshold of The Room, Writer and Professor get cold feet. They’re overcome with second thoughts as a terrifying thought occurs to them.

What if we are strangers to ourselves?

“What if I don’t know what I want?” Writer and Professor, in turn, ask Stalker.

“Well,” Stalker explains to them, “that’s for The Room to decide.

The Room reveals you, it reveals all, everything about you. What you get in and from The Room is not what you think you want but what you most deeply desire.” At the edge of The Room, what had sounded like a dream starts to feel like a nightmare.

Rather than escaping the burnt-out ruins of God’s apocalyptic wrath, it feels like they’re about to enter into his inscrutable judgment.

Anticipation turns to dread as Writer and Professor both have an epiphany that frightens them.

“What if I don’t want what I think want?" In other words, what if they are not who they think they are?

In a book about Tarkovsky’s film, movie critic Geoff Dyer says:

“Not many people can confront the truth about themselves. If they did, they’d take an immediate and profound dislike to the person in whose skin they’d learn to sit quite comfortably for years.”

Eventually, Writer and Professor run away, terrified at the prospect of standing before The Room and having their true selves laid bare.

The movie is dark in tone and hue.

Watching Stalker, this dystopian sci-fi flick from the 1970’s, you’d never log out of Netflix, check it off on your queue, click off the clicker, and say to yourself, “Wow, that was a happy story.”

You’d never leave a review on Rotten Tomatoes to evangelize strangers, “You’ve got to check out this story about The Room “to whom all hearts are open, all desires known, and from whom no secret is hid…”

You might say it’s a good story, a good flick, a good scare.

But you’d never say it was good news.

Likewise, at first and second and third glance, it appears improbable that anyone would so describe this vision unveiled to John. This vision could receive as many readings as the living creatures have eyes and still it will seem dubious that what the Seer sees is gospel. Good news.

Karl Barth says:

“The verdict of the faithful God on the whole world in Jesus Christ, has this side, this dark side as well; it is also the revelation of God’s wrath…”

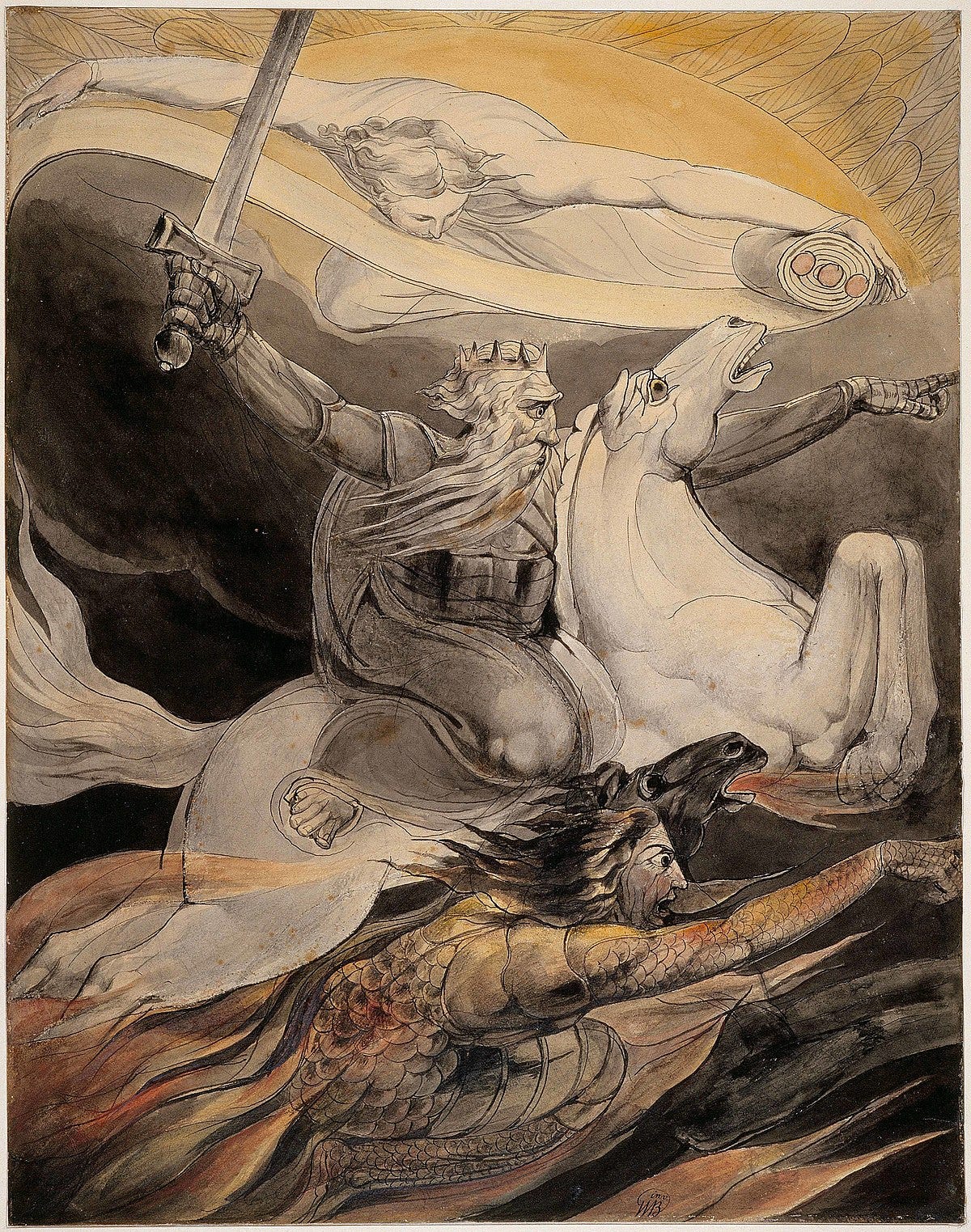

The sixth chapter of the Apocalypse seems a straightforward instance of salvation’s shadow side. The sequence which follows the Lamb breaking open the seven seals is precisely what most people conjure in their minds when they hear mention of the Book of Revelation. When the four living creatures cry out with a voice like thunder, “Come!” they initiate imagery that is as feared as it is familiar. Septenaries of seals, trumpets, and bowls. Horses white and red, black and pale. Riders bringing conquest and unrest, pestilence and death. Martyrs crying out for vengeance.

But the ensuing devastation is not nearly as isolated as even the slain saints demand from under the altar of heaven. When the Lamb breaks the seals and the living creatures send forth the four horsemen, the effect is total. The earth itself appears under God’s attack. The Pale Rider whose name is Death is given authority over a quarter of the world. The second rider on the red horse is given jurisdiction “to take peace from the earth.” So comprehensive is their work that John sees the earth quaking, the sun becoming as black as sackcloth, and the moon turning to a blood redness in the sky.

These scenes the Seer is given to see seem a straightforward example of what Barth calls the dark side of the Father’s verdict.

Johnny Cash clearly thought so. “When the Man comes around,” Cash wrote, “The hairs on your arm will stand up/At the terror in each sip and in each sup.” Tolkien certainly saw it so, taking the four horsemen as his template for the Dark Lord’s Nazgûl, the undead Ring-Wraiths the fellowship of the ring. Ditto Bob Dylan. When the riders approach the watchtower, Dylan sings, the wind begins to howl ominously.

The shadow side of salvation.

“The verdict of the faithful God,” Barth writes, “…is also the revelation of God’s wrath…” Indeed truly awful imagery occasions the breaking of the seals. The violence is such that what the Seer sees seems to contradict the collect for Ash Wednesday:

“Almighty and everlasting God, who hatest nothing that thou hast made and dost forgive the sins of all those who are penitent.”

At first and second and third glance, the God of the Apocalypse may easily appear as the one who hates everything he has made, and with a vengeance. You might say the Apocalypse to John is a good story, maybe a good scare. But good news?

It’s not gospel. It’s the shadow side of the faithful God’s righteous verdict. Right?

And yet!

Nevertheless!

That the Lamb is able to open up the seals and send out horse and rider is in Revelation the gratuitous response to anxious prayer.

Just before chapter six, John beholds a mighty angel who suddenly proclaims:

“Who is worthy to open the scroll? Who is worthy to break its seals? Who is worthy for the Kingdom of heaven?”

Silence follows.

“No one,” John laments, “in heaven or on earth or under the earth was able to open the scroll” and unseal its seals.

As a result, John reports, “I began to weep loudly because no one was found worthy to open the scroll and it’s seven seals.”

Just so, the judgment unleashed by the Lamb is an occasion for joy not dread, praise rather than woe.

This is important— pay attention.

The judgment that transpires is not the dark side of the Father’s faithful verdict; it is instead the deepest desire of the whole company of heaven.

So too, the first living creature cries out with a voice like thunder. Like the theophany to Moses on Mount Sinai, thunder in scripture always signals not divine desolation but God’s transformative action.

And the horses— the Spirit of Jesus first revealed them to the prophet Zechariah as agents of God’s providential will. In the Book of Zechariah, the horses stand idle at pasture while God’s people languish. Therefore, it’s good news that the Lamb is able to send them forth.

Moreover, each of the four living creatures, who are— remember— the evangelists of the gospels, beckons each of the four horsemen with the summons, “Come!” The invitation “Come!” in John’s Apocalypse is a liturgical refrain throughout the book. It’s a call to worship. Thus, the arrival of horse and rider and, with them, God’s judgment is a cause for praise.

This is good news not grim news.

Readers can differ over whether the action the Seer is given to see takes place in John’s own time or in a future that remains outstanding. Interpreters can disagree over whether the horsemen are malevolent powers who are nonetheless within the sovereignty of God or whether they are representations of Christ himself. Believers can debate whether the violence seen by the Seer is actual and historic violence or prophetically symbolic violence.

What is absolute and inarguable, however, not merely in the Apocalypse but in all of scripture, is that the imminent judgment of God of “the quick and the dead” is not the stuff of a ghoulish scare.

It is gospel.

It is promise and good news.

As the apostle Paul writes— writes with anticipation instead of fear, “We shall all stand before the judgment seat of God.”

How is judgment good news?

How does the question which closes this chapter of Revelation open up our future as promise rather than threat; that is, how is it gospel?

“For the great day of judgment has come, and who can stand?”

How is judgment, our judgment as the quick and the dead, anything other than the dark side of the Father’s faithful verdict?

Previously in the Apocalypse, the Spirit had promised John that those believers who washed their robes (that is, who were baptized) and endured in patient faithfulness would conquer in and with Christ. But the judgment unleashed when the Lamb unseals the seven seals spares no one on the earth— spares not even the earth.

Which is it?

Everyone will stand before the judgment seat of God?

Or those washed in the Lamb will be saved?

The tension exerts itself not only in the Book of Revelation but again in the Epistle to the Romans as well. How does Paul’s assertion that “All will stand before the judgement seat of God” square with his proclamation that all will be saved, that God will be merciful to all.

Judgment or mercy?

Which is it?

Who do the horsemen come for and to what end?

Judgment or salvation?

It can’t be both/and can it?

That everyone who confesses Jesus Christ will be saved and everyone will stand before the judgment seat of God?

How do we square the apparent tension?

The question must be resolved because it’s a question you cannot avoid simply by ignoring the book at the back of your Bible. For example, the apostle Paul doubles down and repeats his insistence about judgment in that same letter to the Romans.“Each of us,” Paul writes to the believers in Rome, “will be held accountable before God’s tribunal.” And Paul repeats the assertion almost word-for-word in his correspondence with the Corinthians, “We must all appear before the judgment seat of God.” Even if you dismiss the apostle Paul or John’s Apocalypse, you’re nevertheless stuck with Jesus who, everywhere in the gospels, warns of the coming day of judgment. In his final teaching before his passion, Jesus promises that he will come again to judge the living and the dead, gathering all before him.

Not some.

All.

The “saved” are not spared.

“All shall stand before God for judgment,” Paul says.

Just like Jesus promised.

And a promise from Christ is, by definition, gospel.

Good news.

“The great day of judgment has come,” the Seer hears in Revelation, “who can stand?”

And according to Jesus’s Bible the reckoning that occasions that great day will be a refining. A refining fire, says the prophet Malachi, where our sinful selves will come under God’s final judgment and the Old Adam still in us will be burnt away.

The corrupt and petty parts of our nature will be purged and destroyed.

The greedy and the bigoted and the begrudging parts of our nature will be purged and destroyed.

The vengeful and the violent parts of our selves will be purged and destroyed.

The unforgiving and the unfaithful parts of us, the insincere and the self- righteous and the cynical.

All of it from all of us will be judged and purged and forsaken forever by the God who is a refining fire.

All the shadow sides to our selves will be purged away by the refining fire that is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Now, bear in mind: purgation is not damnation.

Purgation is not damnation.

But neither is it pain free.

Again, how is this good news?

The promise that you will stand before the judgment seat of Almighty God— stripped and laid bare, all your disguises and your deceits revealed, naked, wearing nothing but your true character— admit it, it sounds awful.

At first.

It doesn’t sound at all like anything to which you’d say, “Amen! Me first.”

Six years ago this summer, my oldest son and I milled around Charlottesville. We have a house not too far and often visit. Alexander and I walked around Charlottesville’s Downtown Mall and UVA’s Grounds just hours before the tiki-torch-bearing scare mob descended from the Rotunda shouting “blood and soil” and “Jews will not replace us.”

“Dad, don’t make any jokes about discovering you’re Jewish,” Alexander whispered to me. I laughed, not sure if I should be laughing.

We saw the empty Emancipation Park snaked with metal barricades and draped with police tape. We saw homeless men looking dazed and curious about the stage craft and street theater setting up around them. We saw the lonely-looking white men— boys— wearing white polos and khaki cargo pants, whose faces, illumined by flame and fury, we’d later recognize in the Washington Post. We grabbed a coffee and a soda just off the side street where Heather Hoyer would be murdered the following day.

There’s an elementary school near the park there in Charlottesville, most African American kids. I used to work there in the after school program, Monday through Friday, when I was an undergraduate. Walking around the park with my son, I thought of Christopher Yates, the boy who had no father at home, whom I took to “Long John Slivers” on occasion.

Back then, he had no idea there were people in the world who looked like me who hated people like him simply because they looked like him.

I thought of Christopher.

And I got angry— righteously angry— at those who would fill the park the next day.

“God damn them all,” I whispered, making sure my son could hear.

The following Sunday I led the long pastoral prayer in my congregation. And what I prayed…I prayed about them. I prayed about them, those whose thoughts and actions betray allegiance to the gods of bigotry. I prayed about them, those whose apathy and excuses and silence tolerate hate and harm.

“Bring your judgment upon them, O God,” I prayed in so many words.

God damn them all.

A worshipper took me to task for my prayer that Sunday.

Frank was in his 80’s, a retired Old Testament Professor from Greenville College. He and his wife had moved to my parish a few years earlier to be near his daughter. After the final Sunday service had finished and the crowd had petered away and the ushers were cleaning up the pews, Frank shuffled up to me. He was hunched over as he always is, a knobby cane in one hand and a floppy Bible in a carrying case in the other hand. He stopped, I noticed, to face the altar wall and, with his cane in his hand, genuflected the sign of the cross, tracing it across his lips and then his chest.

Almost always Frank has nothing but unfettered praise for me, but not this time. Shaking my hand, he shook his head in a “there you go again” kind of way.

And he said, “Well, pastor, you certainly were bold to pray for judgment on them.”

I was already beaming.

Ignoring my self-satisfied smile, he added, “You just weren’t nearly bold enough.”

“Professor, I don’t know what you mean…”

He cut me off with a “Tsk, tsk, tsk” sound between his teeth.

“You only prayed for them. You didn’t pray for our judgment.”

“But…” I started to protest, “I was there. I wasn’t the one wearing a hood or carrying a tiki-torch.”

“Everyone in this country is sick with judging— judging and indicting, posturing and pouring contempt and pointing the finger at someone else,” he said, pointing his finger at me.

He raised his voice a little as well as his hunched-over posture: “As Christians, we’re supposed to put ourselves first under God’s judgment, to receive it as good news not bad news…”

“…Because we’re the only ones in the world who know not to fear the Judge…” I completed his sentence for him.

He smiled and nodded, like I’d just passed his exam.

“Christians like to say that every Sunday is a little Easter, but, every day— every day— is Ash Wednesday where we bear the judgment of God on behalf of a sinful world because we know not to fear the Judge.”

He tapped his cane on the carpet and lifted up his Bible by the straps and said, “It’s all right here if folks would just read the thing.”

And it is, all right here.

Even in our passage.

Don’t let the prophetic imagery of John’s Apocalypse lead you astray— the horses and their riders, the sackcloth sun and the blood red moon.

It makes all the difference today that the one who alone is worthy to open up the seals and execute God’s judgment is the Lamb who was slain.

Slain for sinners.

In other words, wherever in history you locate the events of the Apocalypse on a timeline and whoever you identify as the four riders or however you interpret the color of their horses, the cross of Jesus Christ nonetheless remains the hermeneutic for interpreting the Book of Revelation.

Jesus Christ is the hermeneutic.

His blood shed to pardon sinners.

His life offered to justify the ungodly.

The cross is the interpretative key; such that, everything in the Apocalypse that is still not yet has, in a meaningful sense, already happened because all of its events “are already under the embrace of the Love of the Lamb.”

Don’t let the visions vitiate the victory of the cross.

In an absolute and real way, all the events unveiled to John— even if those events are not yet have already happened because the full and final revelation of the Father’s wrath and judgment upon a sinful world is the death of the Son upon the cross for that very same sinful world.

Jesus Christ and him crucified is the interpretive key.

It makes all the difference that the dogma of the Last Judgment comes not at the creed’s end but in its second article, grouped under the finished work of Christ, “…and will come again to judge the quick and the dead.”

Because Jesus Christ is the faithful God’s final verdict upon a sinful world, the Son’s death for sinners now operates as Torah for the Father.

Grace is now law.

A law that God himself is bound to obey.

And therefore you can meet the Lord’s judgment unafraid for no matter what you’ve done or left undone the Father has no other Torah by which to assess you than the Son’s obedient life and faithful death imputed to you.

For those who are in Christ Jesus, the Lord’s coming judgment does not signal damnation rectification.

The God who knows you better than you know yourself and yet loves you— so much so he died for you— he will not leave you as you are.

That’s promise not a threat.

Stalker, that dark, dystopian sci-fi flick from the ’70’s about a Room to whom all hearts are open, all desires known, and from whom no secret is hid…” it’s a disturbing, unsettling, thought-provoking film.

It received hundreds of positive reviews. It helped inspire HBO’s West World. The British Film Institute ranks it #29 on its list of the 50 Greatest Films of All Time.

It’s a good movie.

But you’d never call it good news.

You’d never call it good news.

Not unless the cast included a few more characters, people who thrust the terrified Writer and Philosopher aside at the threshold into the Room and said to them, “Me first.”

Share this post