There is No Reward for Your Virtue

"Thou shalt..." in light of "Apart from works..."

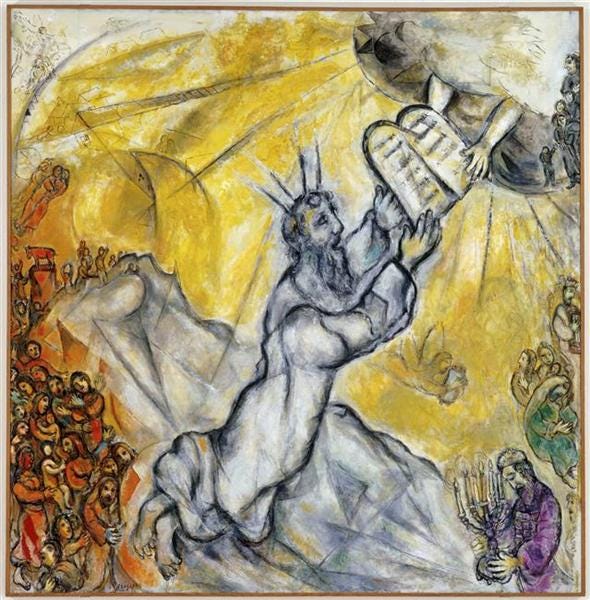

Exodus 20.1-17

For the Second Sunday of Lent, the lectionary offered the church Paul’s presentation of what became the Reformation’s slogan, Justification by grace alone in Christ alone through faith alone— apart from works. In an apparent contrast, the lectionary’s Old Testament text for this coming Third Sunday of Lent is the Lord’s giving of the law to Moses on Mt. Sinai in Exodus 20.

The two Sundays thus give us God’s “Two Words.”

Law and Gospel.

Or, as Karl Barth rearranged them: Gospel and Law.

How can we understand Sinai this Sunday in light of the slogan from last Sunday?What is the relationship between promise and command, done and do? Having heard last week that God rectifies us apart from any obedience on our end, how are we to hear this week that, say, we must not take the Lord’s name in vain?

For Protestants, the slogan is our starting point, justification by faith apart from works.

The obverse of the Reformation mantra is that our work— good or bad— serve a purpose otherwise than making us righteous before God.

As Robert Jenson notes:

“If I feed my hungry neighbor, I need seek in this act no judgment of my life, his life, or even of our life together. My life is undoubtedly a better one if I feed him than if I do not, on several scales of ‘better and worse.’ But my life is no more justified. To the question, ‘ What is your excuse?’ I have no more answer if I feed hi than if I do not.”

From its inception, Protestants have both been offended by and retreated from the proclamation at the heart of their preaching movement.

Not only is justification by faith apart from works the doctrine of predestination put in the passive voice— thus making God the active agent in it all— the Reformation’s central slogan cuts the nerve of our moral narcissism.

The good news in the gospel is that we are not the good news.

The bad news in the gospel is that we are not the good news.

Just so—

To the question, “Why should I feed my hungry neighbor?” the article of justification demands a straightforward answer: So that your neighbor’s belly might be filled.

In the context of the Decalogue, “Why should I not bear false witness?” the article insists we answer simply: Because otherwise leads to societal chaos.

Of course, we can come up with other reasons why it may be a good practice to feed your neighbor (fuller bellies, fewer crimes, more fulfilled families), but the chief article limits how far our answers can veer. If our justification is by God’s grace alone— if the one-way love of God is the sole agent whereby we are righteous before God, then we can NEVER answer the question, “Why should I feed my hungry neighbor?” with anything of the sort: “So I may be justified in my life.”

Importantly, the Reformation’s mantra does not mean that we should serve our neighbor in a selfless way, hoping that the selflessness itself escapes the egocentric trap cautioned against by the article of justification.

Despite the church’s best efforts to obscure the message, the gospel really is as radical as it sounds at first hearing:

The gospel does not merely tell you that you ought not try to get anything out of your good deed for your neighbor.

The gospel insists that you cannot get anything out of your good deed for your neighbor.

The gospel is the good news that you will not be rewarded in any way for your good deed-doing.

In fact, it’s the purpose of the Protestant slogan to make you understand that only the message “You have nothing to gain from filling your neighbor’s belly,” can free you to attend to your neighbor’s belly.

As Jenson writes:

“To the question, ‘Why should I do good?' the radical gospel replies, ‘If you put it that way, no reason.’”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tamed Cynic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.