Revelation 19.1-10

A little over four years ago, a Dallas patrol officer entered the apartment of a twenty-six year old accountant and fatally shot the unarmed man. The police officer, Amber Guyger, claimed she’d entered Botham Jean’s apartment by mistake. Thinking it her own apartment, she believed him to be a burglar.

He had been sitting on the sofa eating ice cream.

The shooting ignited a nationwide feeding frenzy about police corruption and institutional bias. But even more so than the transgression, the news of the absolution that followed both captivated and confused the country.

In the fall of 2019, a Dallas jury found Amber Guyger guilty of murder, and Judge Tammy Kemp sentenced her to ten years in prison.

The trial was over. Justice had been served. Punishment had been meted out. Yet this judge was not done.

Or, as one observer in the courtroom commented, “It was like she had only just begun her work.” First, she invited Brandt Jean to speak to the woman who had murdered his brother. “I don’t want to say twice or for the hundredth time how much you’ve taken from us. I think you know that,” Brandt Jean said, “But I just…I hope you go to God with all the guilt, all the bad things you may have done in the past. … If you truly are sorry, I speak for myself, I forgive you. If you go to God and ask him, he will forgive you.” The African American judge, reporters noticed, wept as Brandt Jean spoke of forgiveness. After speaking with and hugging the victim’s parents, Tammy Kemp returned from her judge’s chamber to the courtroom with her personal Bible in hand. She gifted it to the convicted officer and pointed to John 3:16, “For God so loved the world…” Later that day, Brandt Jean posted on his Facebook Page, “Whenever you open the Bible, the Accuser— that is, the Devil— gets a headache.”

Receiving this judge’s personal Bible, Amber Guyger reached out her arms to the judge. The judge, still in her black robe and pearled necklace, wrapped her in a merciful embrace. “It was like she was sharing in the woman’s guilt and anguish,” said another observer in the courtroom.

The reactions to Brandt Jean’s absolution of his brother’s murderer, the reactions to Judge Tammy Kemp’s act of compassion— the reactions were so swift and so divergent and so dependent on one’s place in society, one’s privilege relative to another and one’s political perspective that, as one legal expert from Stanford told a reporter, “It feels as though we are actually the ones on trial not the accused.”

Many Christians celebrated the display of forgiveness, “This is Christianity,” they said. “This is what the world needs.”

Others, however, themselves also Christians, refused to celebrate the display of forgiveness as somehow a summation of the gospel.

The theologian J. Kameron Carter, for one, questioned it, writing:

"The verdict on the police officer in Dallas of 10 years in prison plus the show of grace and forgiveness by the brother of the murdered victim, just like after the massacre at Emanuel AME, requires that we ask some hard questions: What if “grace” and “forgiveness,” and their compulsory racialized performance in this society, are part of the antiblack world? What if the sacredness of “grace” and “forgiveness” precisely helps keep in place the structures that murder us?”

Put more succinctly, Carter insists that grace, if it is truly God’s grace, must accomplish more than mere forgiveness.

Grace, if it is truly God’s grace, must accomplish more than mere forgiveness.

Exactly because God’s love is God’s justice, Christianity does not envision God’s forgiveness as the triumph of mercy over justice.

Rather, Christianity envisions God’s forgiveness as the triumph of God’s justice in mercy.

While we were yet sinners, the God who is human died for the ungodly— yes. But also, the Lord Jesus promises that those who mourn will be comforted just as those who hunger and thirst for righteousness will be filled. One promise is not to the exclusion of the other promise. These twin promises are as true today in Israel and Gaza, in Moscow and Ukraine and Maine, as they were in that Dallas courtroom four years ago.

The hope of the gospel is not mercy instead of justice.

The hope of the gospel is justice in mercy.

In other words, the hope of the gospel includes the promise of hell. The process of hell is constitutive of God’s heaven.

The promise of heaven is unintelligible apart from the process of hell.

That is, God is heaven and God is hell.

In popular imagination, the last book of the Bible, the Unveiling to John, is likely the scripture most often associated with the doctrine of hell, but heretofore I have avoided addressing it directly.

I have bided my time.

I have been waiting for this passage because only when you appreciate how the scriptures conceive of the character of salvation will you understand why the ancient church fathers and mothers— who complied the documents we call the New Testament— insisted on the reality of God’s hell.

Only when you understand the kind of salvation the scriptures anticipate will you understand why the fathers insisted on the reality of hell— in the way they understood it.

A holy apprehension of hell is intelligible only when you see that salvation is the Marriage Supper of the Lamb.

The prophet’s phrase meta tauta (“after these things”) in verse one signals a fresh set of visions, yet the jubilation that follows comes as the consequence of the fall of Babylon in the previous chapter. The kings of the earth mourn Babylon’s demise but the people of God celebrate it. The saints laud the victory of God by lifting up the psalmist’s familiar cry for the first time in the Apocalypse; they shout “Hallelujah,” which means simply, “Praise Yahweh.” The company of heaven sings “Hallelujah” not only because the devil's tyrants have been toppled but because the Father’s Son will finally wed his spouse and take her into his body.

“Let us be glad and rejoice, and give honor to him: for the marriage supper of the Lamb is come, and his wife hath been made ready.”

Straightforwardly, when the Spirit of Jesus finally reveals to the prophet the event of salvation he shows him nothing other than the consummation of a wedding between himself and his bride.

Such imagery for salvation is not new in scripture.

Before his passion, Jesus promises his disciples that he is about to go to prepare a place for them in his Father’s house. It’s so familiar a scripture— a passage we associate with funerals not weddings. It’s so hackneyed a text we miss that Jesus is comparing salvation to the culmination of a nuptial ritual. In first century Jewish weddings, when a bridegroom betrothed himself to a bride, before the wedding ceremony, he would first go to his father’s house and build an addition onto the family home. Only after the bridegroom had prepared a place for his bride at his father’s house would the bridegroom return, make his promise of forever to his bride, and then take her to the place he had prepared for them and there take her unto himself.

The candid parallel between sexual union and salvation may make you squirm, but it’s the plain teaching of the scriptures.

The apostle Paul perhaps had Jesus’s farewell discourse in mind when, in his letter to the Ephesians, he interprets the mystery of sexual union by relation of Christ and the Church and by relation to the triune life itself.

This linkage between the erotic and the eternal is not limited to the New Testament.

In the Old Testament— the scriptures by which the church understood herself— Israel experienced the favor of her God as his burning, unquenchable, passionate love for her. The Book of Deuteronomy insists upon it as a matter of dogma. The Lord chose Israel not because Israel had a particular proclivity for covenant or unique potential for faithfulness.

The Lord chose Israel and made her his own for no other reason than that the Lord loved her.

Israel’s election, her chosenness, is the result neither of a rational decision nor an arbitrary one. God is the God of Israel because the Lord fell in love with her.

Meanwhile, the Song of Songs, a biblical book that is all about erogenous zones and seductive aromas and lovers looking for a place to be alone, unabashedly asserts that human sexual love is the most precise analogue of the love between the Lord and his people.

And take care to notice the claim made there. Sexual love is only an analogy.

Salvation is like a lover delighting in their beloved and enjoying their bodies’s grace.

But—

Of all the analogies we might use, out of all the other images and pictures we might conjure, sexual love is the most precise analogue.

And for this reason the Song of Songs was quite possibly the book of the Old Testament most important to the church fathers who compiled the New. Thus, in the Song of Songs, Israel does not long for forgiveness of sin or rescue from exile or for other gifts detachable from the Giver. Israel longs simply for the Lord himself. And it is a longing precisely for the Lord’s touch and kiss and fragrance. Just so, the Old Testament imagines lovemaking out of doors in a springtime Eden as an image of the Lord with his people in the Last Future.

Salvation, the Song extols, is akin to a woman sheltering under her lover and tasting his fruit.

Whatever salvation is, it’s most like that.

For Israel, “the Lord is simply lovable, and salvation is union with him, a union for which sexual union provides the most precise analogy.” Or as St. Augustine captured this very theme in the Confessions, “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they find their rest in you.”

On Saturday, I went to the hospital to visit a dear friend whose wife had suffered a massive heart attack the night before.

She had collapsed in their living room just before they left for a dinner date.

Steve had tried to mimic the chest compressions he had seen in movies.

By the time the ambulance arrived, Kathy’s heart had been still for over three minutes.

After cardiac surgery, Kathy’s lungs filled with fluid and so she was intubated, the ventilator preventing her breath from becoming air.

When I knocked on the glass door in the ICU, Steve was holding his wife’s hand and whispering in to her unresponsive ear, “I love you. I love you. I love you. I love you.”

No longer his pastor, I tried to be his friend.

I sat down next to him and put my arm around him and listened to his worries about his children, his regret about not letting her die quickly in their home, and his fear of living in that home after she dies.

At one point in our conversation, he looked over at me, with raised emphatic eyebrows, and he pointed at her and said, “All I want to do— all I want to do— is pull all that stuff off of her and give her a kiss on the lips.”

He was pointing at the tubes obscuring her nose and mouth and neck.

“All I want to do is pull all that stuff off of her and give her a kiss on the lips. Is that crazy?”

“No, it’s not crazy,” I said, “It’s holy.”

It’s salvation.

The erotic terms in which scripture envisions the End may discombobulate us or even embarrass us; nevertheless, they are a logical correlative to the consummation of history.

That is, scripture likens salvation to the consummation of a marriage because scripture anticipates the consummation of history.

When history ends, there will be nothing left for us to enter into other than God; just so, sexual union is the most precise analogue for the Lord’s End with us.

As Robert Jenson writes,

“Let me put the question: What could be an end of history, other than a sheer and thus meaningless termination? God, we said, creates a history that is a whole, a creation, only because it has an end. But what could "an end" be? If we got to history's end, what would we discover? That time and discourse had simply stopped? How then could we discover this? And why anyway would one want to get to such a point? Is the notion even intelligible?

The one conceivable end of history, that will not cancel the whole being of history, must again be a sublation. But into what? When creation ends, there is only one thing left to be taken into, and that of course is God. Thus the doctrine of theosis, the doctrine that our end is inclusion in God's life, is not merely the brand of eschatology preferred by the Eastern churches; it names the only possible "end" of a creation, the only possible end of being that is history and drama.”

Scripture envisions salvation in such carnal terms because in the End, when God consummates history and there is no remainder to creation, the Father’s people— the Son’s bride— will enter into his triune body.

Because salvation is union with God, the process of God’s hell is necessary for God’s heaven.

A bride must be prepared for her groom.

It’s the fourth verse of Charles Wesley’s hymn, “Finish then, thy new creation; pure and spotless let us be…” Because salvation is union with God, the process of God’s hell is necessary for God’s heaven. As imperfect as the word process is, it is an essential word in that it reminds us what the church fathers so clearly taught but what we so often fail to heed.

Namely—

Heaven and hell are not locations.

They are relations.

Hell is not a place.

Hell is a process.

To be clear, the doctrine of hell as the church fathers taught it is not hell as Michelangelo or Bosch painted it. The doctrine of hell as Gregory of Nyssa or Origen taught it is not hell as Dante described it. The doctrine of hell in the tradition or in the scriptures is not the same as the hell of popular imagination.

Hell as a place of eternal conscious torment into which God sorts individual people— such a hell “requires a mythical sort of God.” Hell so conceived is unworthy of God and at odds with the gospel. God is not cruel. God is just and loving. Indeed, properly understood, “God is just” and “God is loving” are redundant statements.

Therefore, the doctrine of hell is a necessary component to the gospel hope because without it God’s character is impugned. God cannot fail to do justice for those who were wronged, even as he has mercy on those who did the wrong.

Hell is not so much for sinners as it is for those who sinned against sinners, those who took advantage of others’s brokenness or oppressed them in their misery.

God damns the abusers, the victimizers, the violators. And he damns them both for their own sake and for the sake of those abused, victimized, and violated. No wrong can go unanswered.

Again, this is the straightforward teaching of the church fathers, many of whom simultaneously taught that all shall be saved.

In the tradition— the tradition that gave us the New Testament— hell is the name for the process in which God separates sinners from their sins, destroying not only those sins but the evil that animates them. Hell is what the theologian Pavel Florensky called:

A “fiery surgery,” in which “every impure thought, every idle word, every evil deed, everything whose source is not God, everything whose roots are not fed by the water of eternal life … [is] torn out of the formed empirical person, out of human selfhood.”

In other words, hell is the process at the end of which nothing is left but pure creatureliness, burning with the divine light in the divine love.

This hell is what the scriptures announce when they declare the “the Lord is a refining fire.”

Preaching on this doctrine of hell, George MacDonald insists:

“Love loves unto purity … Therefore all that is not beautiful in the beloved, all that comes between and is not of love’s kind, must be destroyed. And our God is a consuming fire.”

For MacDonald and, just so, for the tradition, God is heaven and God is hell. Heaven and hell are not locations. They are relations.

In particular, hell is the way God relates to us; so that, both we and those we have sinned against are delivered from our sins.

As the Irish theologian from the Middle Ages, Eriugena, puts it:

“It is not part of God’s justice but wholly alien from it to inflict penalties on what he has made. Instead, God inflicts penalties, justly, on all that he has not made.”

That is, sin, not the sinner, evil, not the evildoer, is destroyed. Murder and abuse and rape and despotism and racism and lying, like all evils, are God-damned and forever eradicated. God does not merely “forgive” the rapist and then expect the one who was raped simply to accept that this forgiveness is just. God, somehow, consumes the sin itself, the evil that was done, so that both the victim and the victimizer are made whole.

Hell and heaven do not name the sorting of individuals according to who did and did not believe.

In the End, there is neither the good place nor the bad place there just is God.

And because he is the Bridegroom who will take us into his body, our sins must be separated from us.

This is the doctrine of hell.

This is hell as the fathers taught it. Hell as purgation not perdition. Far from being frightening news, rather than being the gospel’s contrary, this doctrine of hell— hell as separation of the sinner from his sin, hell as the eternal eradication of evil—only this doctrine of hell can answer the problem of evil.

The intersection of justice and mercy in Amber Guyger's judge, the offer of undeserved forgiveness from her victim’s brother, it not only perplexed the secular media it provoked outrage from observers.

Meanwhile many religious people meanwhile insisted that Brandt Jean should not have forgiven his brother’s trespasser in the absence of any penance.

One religious leader tweeted, “Forgiveness without justice is injustice.”

And, of course, he was correct, forgiveness without justice is injustice.

I mean—

Should the mothers mourning in Israel and in Gaza simply forgive the terrorists who beheaded their babies or the soldiers bombing their children?

Forgiveness is too weak a word to summarize the gospel hope.

Hell as a place of eternal conscious torment is anathema to the gospel.

Hell as the process by which God separates sinners from their sins is righteous.

Is it possible that some creatures are so consumed by their sins that nothing of them will remain after they’ve encountered the consuming fire of God’s love?

The tradition has been reticent to answer.

Nonetheless, hell as purgation is not a doctrine to be avoided. It’s a doctrine to be celebrated— a promise to pray for and a hope to cling to— because it teaches us better than anything else that God’s forgiveness is not the triumph of mercy over justice but the triumph of justice in mercy. Scripture is clear, Yahweh offers no amnesty to the wicked. The Lord insists on a reckoning. In the end, simultaneous to the End, the consuming fire of God’s love will actually make all wrongs right, transfiguring what we have done and what has been done to us without simply undoing what has happened.

Because God is loving, we can be certain of the dawn.

Because God is just, we can look forward to hell.

Robert Jenson asks what makes final salvation in fact both final and salvation, and he answers:

“Precisely that we are set right with each other, that I have the joy of God’s rebuke for my sin against my brothers and sisters, and the joy of seeing the repair of my injuries to them, at my cost.”

That is the hope— first God is hell; then God is heaven.

That is what the Song of Songs means by declaring that love never fails.

I visited my friend last night in the hospital.

After I prayed, I watched as he delicately, meticulously moved all the tubes and tape safely to the side of her mouth— moved everything that was in the way between them— so that, he could kiss his bride.

The hope called hell is that in the End God will do likewise with us.

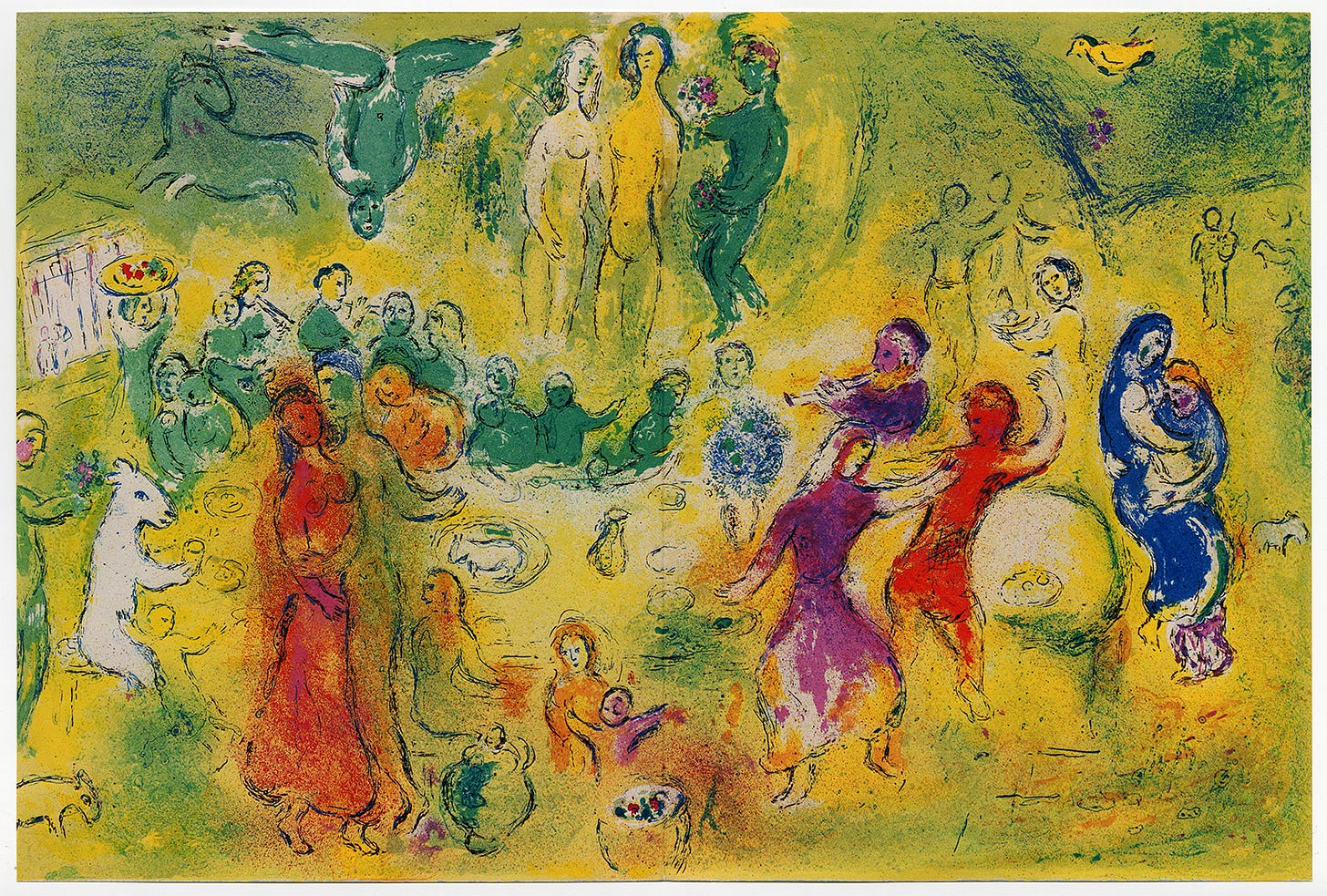

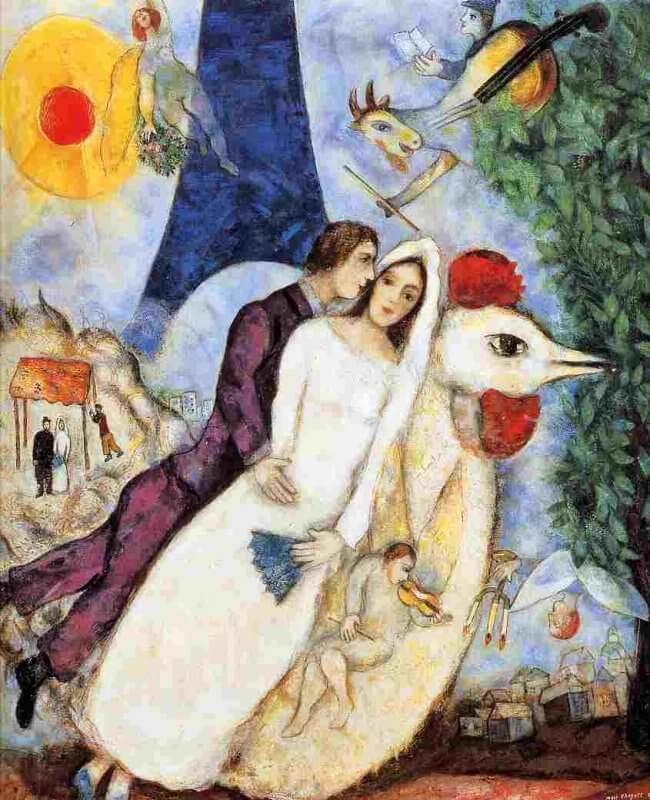

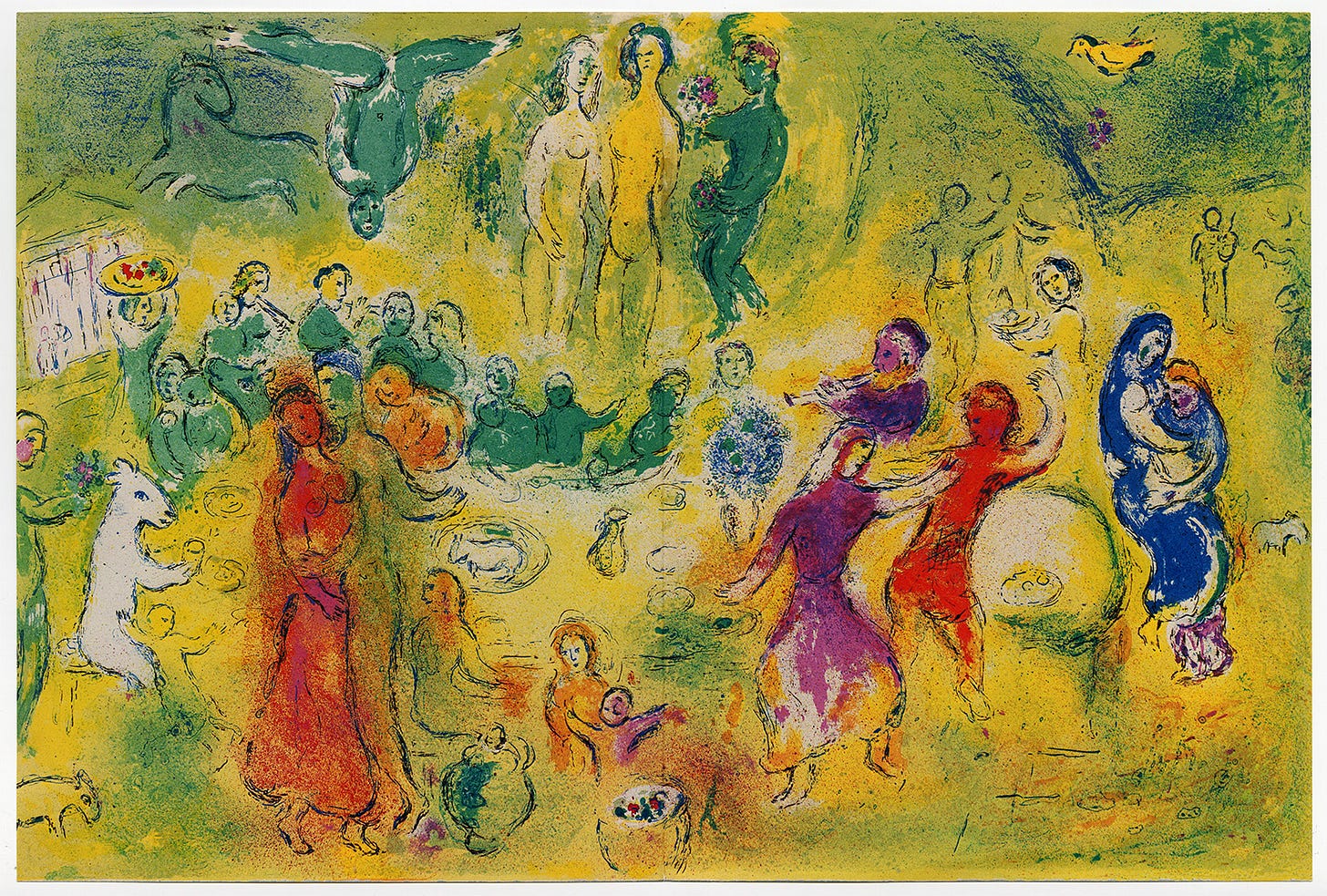

(images, “The Wedding,” by Marc Chagall)

Share this post