The lectionary for this Palm Sunday assigns the church Psalm 118, a prayer whose answer the welcoming crowds impute to Jesus as he rides a colt into Jerusalem.

Every year during Passover week Jerusalem would be filled with approximately 200,000 Jewish pilgrims. Nearly all of them, like Jesus’s friends and family, would’ve been poor. Throughout that Holy Week these thousands of pilgrims would remember how they’d once suffered under a different empire and how God had heard their cries and sent someone to save them.

“Hosanna!” they’d shout for Messiah, quoting Psalm 118, “Save us!”

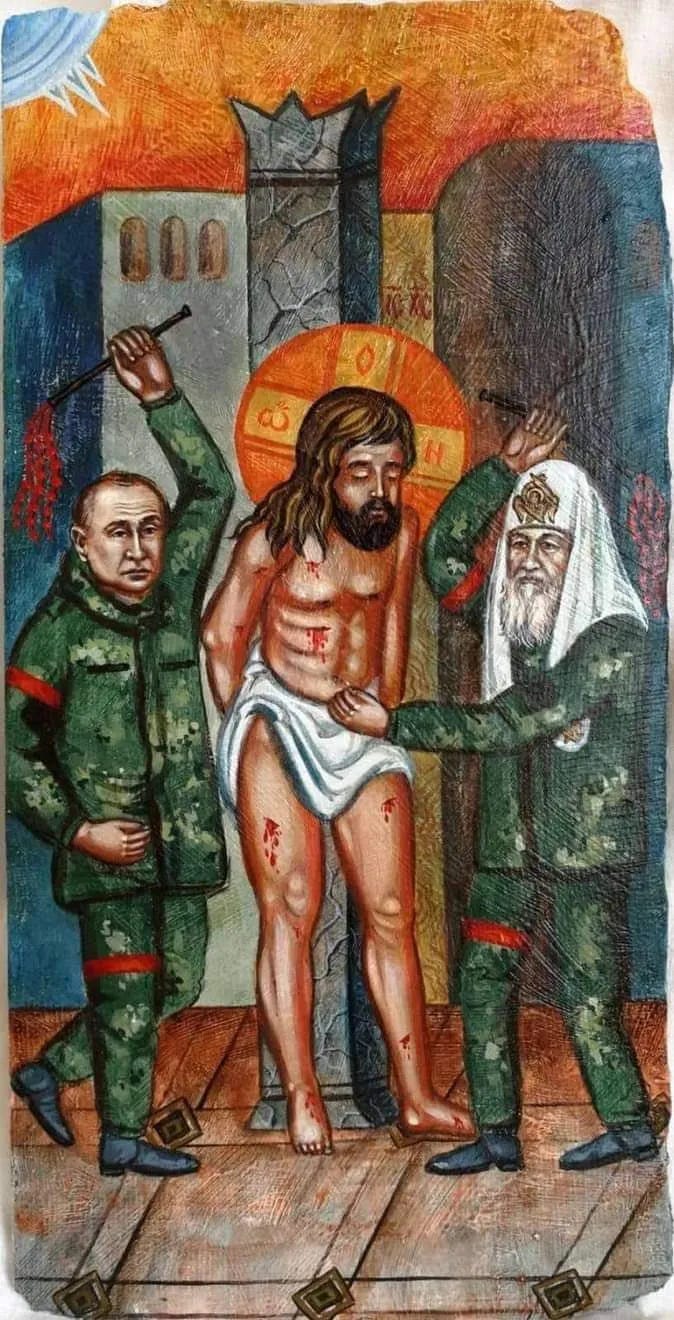

Every Passover therefore was a possible inflection point. Flexing his political muscle, every year at the beginning of Passover week, Pontius Pilate would journey from his seaport home in the west to Jerusalem, escorted by a military triumph, a parade of horses and chariots and armed troops and bound prisoners, all led by imperial banners that declared “Caesar is Lord.” A gaudy but unmistakeable display of power.

Only one year, at the beginning of that same week, Jesus comes from the east. His “parade” starts at the Mt of Olives, two miles outside the city, the place where the prophet Zechariah had promised God’s Messiah would one day usher in a victory of God’s People over Israel’s enemies, thereby establishing peace.

For those who think Christianity is primarily information about access to heaven and believe that Jesus is Secretary of Afterlife Affairs, Palm Sunday is an uncomfortably and overtly political occasion. The passages assigned for Palm Sunday will not abide the assumption that the good news of the gospel is little more than a salve for weary souls.

Palm Sunday marks Jesus’s penultimate, prophetic mockery of Rome’s pretensions.

And no reader of the Old Testament can miss that the defeat of Israel’s enemies was, just so, the simultaneous defeat of her enemies’s gods.

Thus—

The gospel is more than comfort for sinners.

The gospel is more than faith-based morals for our politics.

The gospel is more than time-tested principles for our personal projects.

The gospel is a summons.

We spend a lot of time in the church attempting to clarify the answer to the question, “What is the gospel?” And at a time and in a denomination where the answer to that question is increasingly confused, it’s an appropriate question to ponder.

But the answer to the question, “What is the gospel?” will always only be incomplete if we cannot also answer a corollary question, “What is the gospel supposed to do to its hearers?” What is the Gospel meant to do on its hearers?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tamed Cynic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.