Revelation 8.1-13

In his memoir, Accidental Preacher, Will Willimon divulges few details about his “Daddy,” whom he knew little and seldom saw. The elder Willimon was a scoundrel in a small Southern town. A conman and a convict, Will grew up knowing his father as little more than as a source of shame for his family. In one of his first appointments as a young pastor, Will was about to lead his dysfunctional congregation’s nativity worship when he learned of his father’s death.

Will writes:

“My I was appointed pastor to a forlorn congregation that was planted by Buncombe Street Church when I was a child. By then my father had shown up in town once or twice, unannounced. We met for coffee, but [my wife] and I told neither [our daughter] nor [our son] about their long-gone grandfather because it seemed a dishonor to Mother. As my father was dying of cancer, visiting us was his way of “settling my debts”—an absurd supposition for a man who owed everybody. How, in God’s name, was he going to repay me? We would look ridiculous, a dying old man and his middle-aged son at last attending the Boy Scout Father-Son Banquet.

It was Christmas Eve 1981. Northside United Methodist Church had a rough ride the years prior to my arrival as their new pastor. Things were so bad they found neither the funds nor the enthusiasm even for a Christmas service the previous year. The dispirited congregation needed one undeniable success. Even if I singlehandedly had to mold the candles, grow the poinsettias, and falsetto-croon “O Holy Night,” by God my first Northside Christmas would be a candlelight extravaganza of Yuletide emotion. As I was putting the finishing touches on my sermon for that night’s service, my brother Bud called.

“Daddy just died.”

The father I barely knew selects that night—my biggest night at my new church—for his exit, this time leaving for good. As we drove to church that night, I was ashamed of my lack of response. Though I tried to lament the tragedy of it all, my grief was no greater than that of a kid staring at a speckled hound at the bottom of the dry well.

We hurried into church. I put on my robe, pulled tight the cincture, directed the candles to be lit, and formed the choir for the introit.

That Christmas Eve at sad Northside, as at many other times and churches, I practiced the art of pastoral repression in service to my vocation. I stood up and played the preacher. Don’t accuse me of deceit or denial—that night I was almost grateful for having something to pray over other than myself, pleased that baptism had given me a church family more messed up than my own, glad that a pregnant virgin is more newsworthy than a son unable properly to grieve the death of a failure at fatherhood.

There was only me to say the divine words they couldn’t say to themselves. Somebody’s got to deliver the news, the good news for all who dwell in the land of darkness, whether it be east of Eden or on the north side of Greenville. And wonder above wonders, in a dejected little church that nobody has heard of on ironically named Summit Drive in Greenville, damn South Carolina, with an emotionally inept preacher without even the grace to mourn his departed thief of a father, God with Us.”

God is so determined to be with us, Will writes, the angels carried me that night through the worship of their Lord.

The year his father died, the introit for the nativity service was not what Will had preferred, “In the Bleak Midwinter,” but “O Come, All Ye Faithful.”

“O come and behold Him, born the King of Angels…”

“O sing, choirs of angels…”

The King’s angels do more than sing.

The interlude between the sixth and seventh seals, with its vision of the victorious saints clothed in robes washed white by the blood of the lamb, offered a respite from the unrelenting torrent of judgment unleashed by the four horsemen of the apocalypse. In place of the world torn asunder, chapter seven showed the church triumphant. In place of the terrors of history, the interlude provided a glimpse of the future’s Fulfillment.

But the reprieve from judgment was only temporary.

The interlude ends.

The Lamb opens the last seal and Revelation resumes its “controlled descent into chaos.”

And what happens initially when the Lamb unseals the final seal is anticlimactic. There is neither horse nor rider. There are no peals of thunder. There is not a cacophony of cataclysm.

There is only silence…

“There was silence in heaven,” the Seer hears, “for about half an hour.”

As Bonhoeffer writes:

“The proclamation of Christ is the church speaking from a proper silence.”

Since Christ is not only the agent who opens the seal but the revelation it contains, at first, among all the creatures of heaven, there is nothing but silence.

And then…angels.

The Seer sees seven angels gifted seven trumpets. The Seer sees still another angel, armed with a golden censor, mixing a multitude of incense with the prayers of the saints on earth; so that, they might bend the ear of the Lord in heaven. Just as Ezekiel saw, the Seer sees the angel fling fire upon the earth from heaven’s altar, wreaking thunder and lightening and earthquakes. And then the Seer sees four of the seven angels blast their trumpets, each in turn, each letting slip the Lord’s unmaking of the world.

The vision ends with an eagle crying with a loud voice “woe.” Like Jesus does in the Sermon on the Plain, the eagle cries loudly “woe.” The eagle attests that he cries “woe” because there are still more angels on the way.

In a Christmas Eve sermon from 1972, Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann recalls how his ten year old son was tasked with writing a nativity play for his Sunday school class. The boy made it a dialogue between two of the friendly beasts at Bethlehem.

Donkey: It sure is cold, is it not?

Lamb: It sure is.

Donkey: Do you know what year it is?

Lamb: I think it is the year 1.

Donkey: Hey, there’s something in the sky.

Lamb: Is that not a star?

Donkey: Yes, there is something right by it. There are two of

them.

Lamb: Who is that over the hills?

Donkey: It looks like some people coming to get their taxes in

the books.

Lamb: But the inns are all full. Maybe they will come here,

huh?

Donkey: Here they come.

Lamb: Be nice to them, huh?

Donkey: She looks like she is going to have a baby!

Lamb; Hey, look over the hills. It looks like some kings.

Donkey: She’s having a baby—look, some angels.

Lamb: Gosh, some angels.

Much more so than any other book of the New Testament, the Apocalypse to John is “one long display of angels.” This is not surprising. Just as Revelation is an unveiling to John of heaven so too is it a glimpse of the creatures who habitate there. In fact, as the Apocalypse narrates commerce between heaven and earth, the Lord’s angels are its primary protagonists.

Angels are the active agents in the narrative.

This makes the Book of Revelation in general and the seventh seal in particular as appropriate an occasion as any other to dwell on those creatures that Karl Barth calls “God’s ambassadors, the opponents of God’s opponents.”

Are we able to say anything more about them than, “Gosh, some angels?”

John Page was both a Virginia statesman and a person of faith. During the American Revolution, he exchanged much correspondence with Thomas Jefferson who was also a Virginia statesman but was not a believer. In one of his letters to the future president, Colonel Page quoted from the Old Testament Book of Ecclesiastes, writing: “We know that the Race is not to the swift nor the Battle to the Strong. Do you not think an Angel rides in the Whirlwind and directs this storm?”

I wonder if John Page’s assertion embarrasses you as much as it likely embarrassed Mr. Jefferson. We sing about their singing at Christmas, but, otherwise, when it comes angels most believers do not appear to have much more to say than…silence. Our reticence to speak of angels (with anything more than sentimentality) aligns us with Jefferson, the Enlightenment skeptic, rather than Page, the Christian believer.

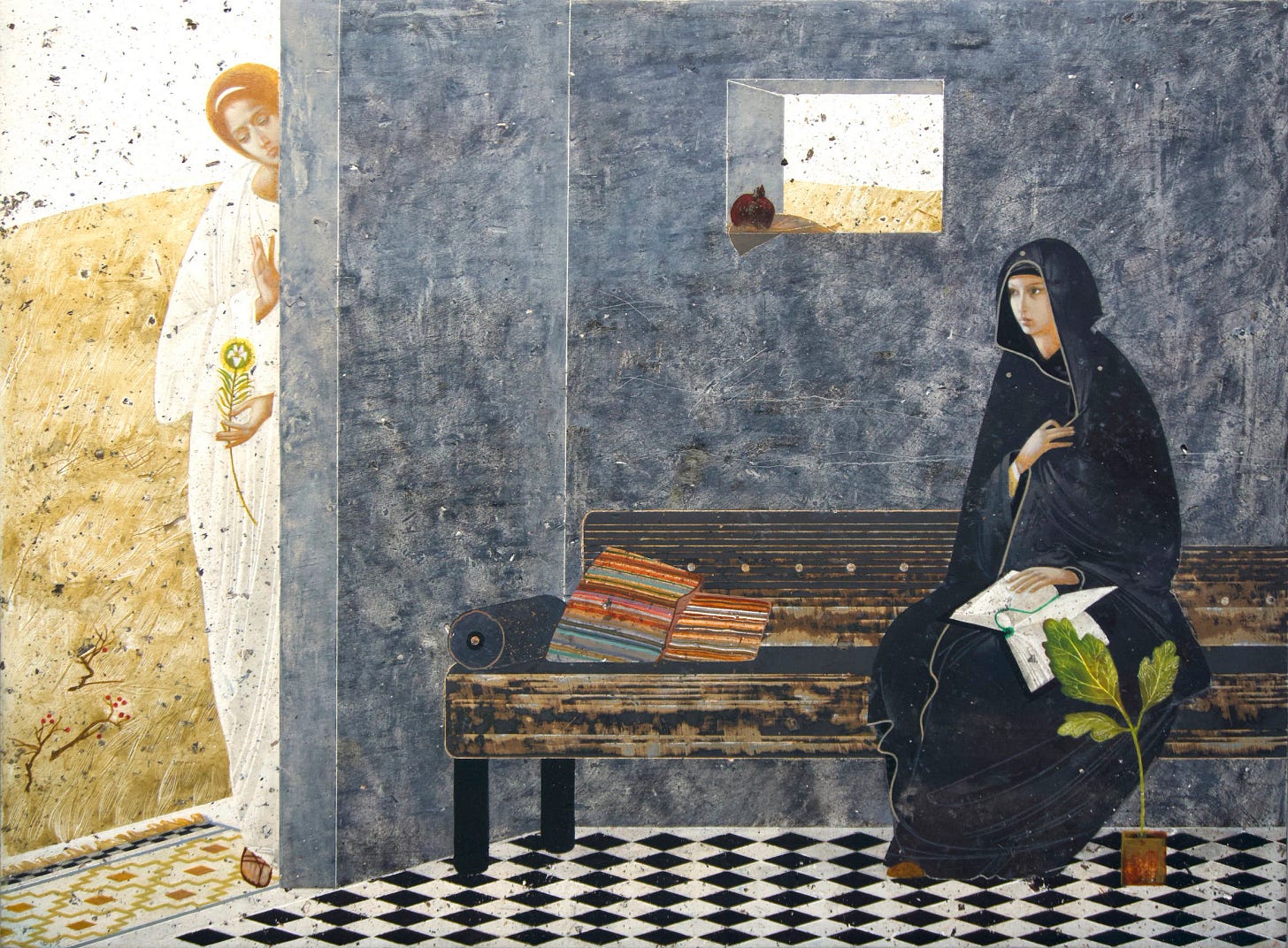

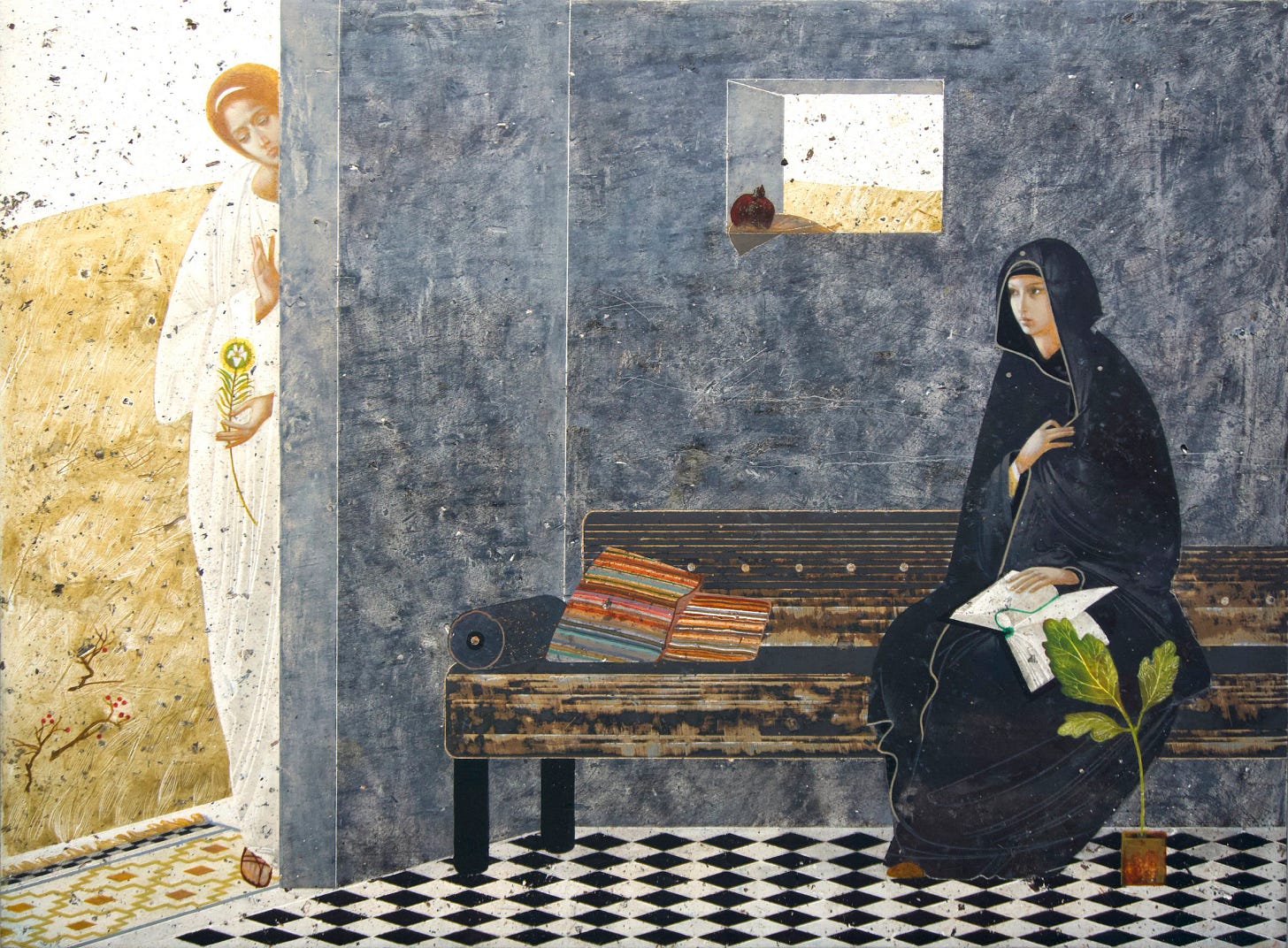

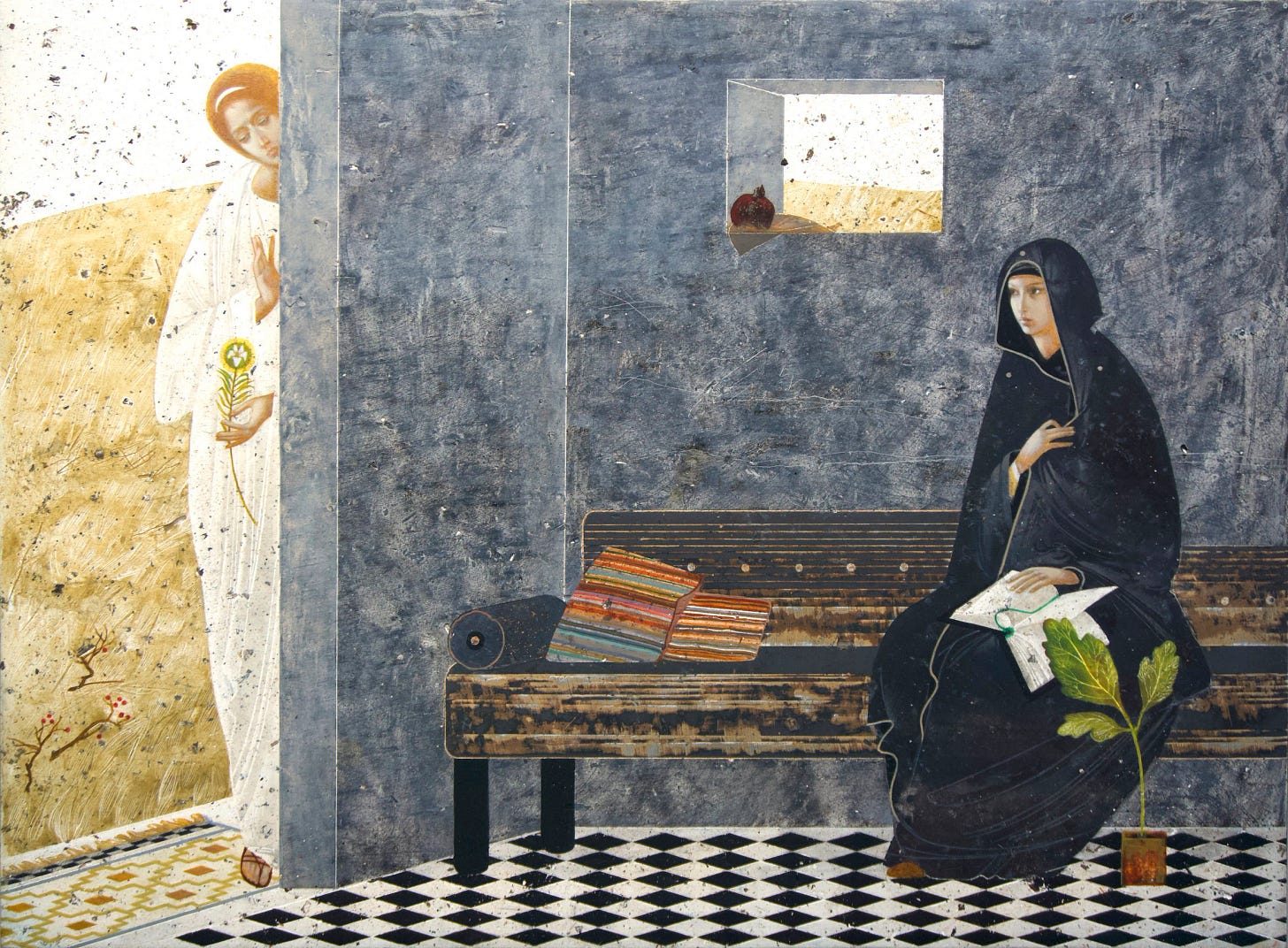

Yet, as Karl Barth insists, the angels are not like the March hare. “The angels,” Barth argues, “are not an absurdity or curiosity which we are at liberty to reinterpret, to deny, or to replace by curiosities of our own invention.” We can neither remove the angels from the gospel nor can we demythologize their role in its drama, for the glad tidings of the gospel begins with Gabriel’s announcement to Mary that she would bear God in the ark of her belly.

Thus Barth concludes:

“The real question is not what we can make of angels. It is whether in our supposed Christian faith and proclamation we really have to do with the word of God attested in the Bible if we can easily ignore angels and regard them as superfluous, or cheerfully and confidently ask what we are to make of them. In other words…there may well be given here a confession of poverty in respect of our Christianity. We may be forced to admit that we have not really noted the word of God as it is really given. We may have to affirm that we have cause to regard not the angels but ourselves as superfluous and in need of correction.”

Barth’s point is that the angels persist for us as a stubborn but redressing reminder that Christianity cannot be reduced to ethics.

The gospel refuses to be watered down to good-deed-doing. If you deconstruct the faith such that the angels no longer play a necessary role, then you have, in fact, fashioned an idol. Inconveniently perhaps, the Jesus who teaches the golden rule is the same Jesus who was aided by the angels in the desert and the garden. Indeed we would not know Jesus lives with death behind him if an angel had not first told us the good news.

Angels appear all over the Bible. And they do more than sing on high, “sweetly o’er the plains.” So what are we able to say about them besides, “Gosh, some angels?” And what can I promise you on the basis of them?

Note how the first article of the creed begins.

“I believe in God the Father, the Almighty, maker…”

Maker of what?

Heaven and earth.

According to the dogma, heaven is created along with the earth, as earth’s “boundary by mystery.”

God creates heaven when he creates the earth. Heaven is the space God makes in creation for himself. That is, heaven is not eternal. No wise different than the stars or the sea or aardvark, heaven is an item in God’s creative act, and the angels are the creatures made for that mode of God’s creation. Just as Sons of Adam and Daughters of Eve are creatures of the earth, the angels are creatures of God’s heaven.

They are creatures.

They are creatures like us. Except, the Risen Christ is “far above” them. And, as we will be made like him, in the Resurrection, we will be above the angels as well.

Angels are creatures.

Thus, the first rule in defining angels is that we are not to relate to them religiously. We are not to put our faith in them.

Angels are servants.

Scripture frames this second rule restrictively. Angels are creatures of God’s hand. Either they are God’s immediate and wholly dependent servants or they are evil. An “angel” with a will of his own is a demon.

Angels are immediate and immaterial.

As the ancient church father John the Damascene puts it, though the angels’s “nature is graced with immortality,” they are “bodiless and immaterial” and so “changeable.” They exist, Barth writes, only in their coming and going, a coming and going that just is God’s will. Just so, they appear as God commands and requires.

I was struggling to prepare my first Christmas Eve sermon over twenty years ago. I confessed my troubles to a professor, “There’s angels all over the story. I don’t know what to do with it. It reads like a fairy tale so soon after the twin towers fell.”

“Fairy tale?” Dr. Jacks asked, “You have trouble believing in angels?”

He didn’t wait for any limp reply I might’ve mustered.

Instead he told about a winter day a few years earlier. Heavy snow fell as dusk settled over New England. He and his wife were driving to their daughter’s house to visit when their car broke down. Cell phones were not yet a ubiquitous device, and Dr. Jacks and his wife were both old, too old to be early adopters of cell phones and too old to sit for long in an idle car in single digit weather.

“I was sitting behind the wheel,” he said to me, “reassuring my wife that all would be fine while I wondered how long we could sit in the car or how far I would get walking in the snow with a cane in one hand and my wife on my other hand.”

I squinted at him and he leaned closer to me across the dining hall table.

“All of a sudden, like an answered prayer, this young couple pulled up alongside us in a station wagon— the kind with wood paneling on the sides— and offered us a ride.”

“You got in the car with complete strangers?!”

He nodded.

“Of course, I…” and his voice trailed away as he recalled the incident, “I just knew.”

“You think those two were angels?” I asked prematurely disgusted at his sloppy thinking and hasty conclusion.

“Wait,” he said, “I’m not finished with my story.”

He sat back up and smiled and laughed a slight, joyful laugh.

“Twenty minutes later,” he said, “they dropped us off at our daughter’s house. She looked around her property as we climbed up the steps of her big front porch. I turned around and waved at the couple who had saved us and my daughter said, with alarm in her voice, “Dad, who are you waving to?” I told her, “The couple in the station wagon who drove us the rest of the way.” And she said, “Dad, there’s no one there. Look, there’s not even any tracks in the snow.””

I just stared at him, a fat crumb from my sandwich hanging off my dumbfounded lips.

“Don’t ever mistake the story for a fairy tale,” he said, pointing his long, bony finger at me.

And then, before he got up to leave— I didn’t know it at the time— he quoted Auden:

“Nothing that is possible can save us.”

The seven angels that John sees with seven trumpets are the seven archangels of Judaism: Uriel, Raphael, Raguel, Michael, Sariel, Gabriel, and Remiel. Of the seven, only Gabriel and Michael otherwise appear in the New Testament; however, the fact all seven appear in the Apocalypse shows that they nevertheless remained a part of the ancient church’s mental furniture. Indeed it isn’t simply that the other five archangels don’t appear in the New Testament angels themselves have a narrow role in the New Testament.

Angels appear in discrete moments in the Gospels. Angels appear at particular points in the Book of Acts. And angels appear all over the Apocalypse but not so the remainder of the New Testament.

In the rest of the New Testament, angels appear only at precarious moments.

A decade ago, the NYTimes featured an interview with a Polish director named Agnieska Holland. At the time, Holland was promoting her new film, In Darkness, which had been nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Film.

The plot of In Darkness concerns a Polish sewer worker (and part-time thief) who takes it upon himself to hide Jews in the sewer during the Nazi era. Holland had previously directed the movie Europa, Europa. The reporter asked her why

she had decided to do another Holocaust movie, having allegedly sworn off the theme.

She changed her mind when it came to In Darkness, she said, “The main character, this Polish guy, was ambiguous. What was interesting was not the mystery that people can be terrible. Humanity has a tendency to be terrible. What intrigues me is that in those circumstances [the extremity of life in Poland under Nazi occupation] somebody acts in a good way who doesn’t have deep reasons to do so.”

The movie maker called the sewage worker a mystery.

The Bible gives us a synonym for mystery.

God raised Jesus into the eschatological future— the Future. As the place where the risen Christ sits at the Father’s right hand, heaven is future.

Heaven is the created future’s presence— as future— with God.

In heaven, the future is present for God. This is ungraspable for us. For John of Patmos, it is glimpse-able only in images and sounds and riddles.

Pay attention now:

If heaven is the future Fulfillment into which the risen Christ ascended, then angels are instances of the triune God reaching into the present— from that future— to pull history towards the End that God desires.

Angels are events of God tweaking the plot of the story he is making with us.

Angels are happenings of authorial intrusion.

Angels are those points where eternity clips time.

To get the story back on track, God sends angels.

Thus, the world is not a machine.

It is creation.

And from one part of creation to another, from heaven to earth, God, with his angels, can move to and fro. But the Lord does so, the New Testament suggests, only sparingly. Outside the Apocalypse, there aren’t that many angelic instances in the New Testament.

Angels appear only at what Robert Jenson calls “ontologically perilous junctures.”

They show up at the conception and the birth of the human-who-is-God, at the resurrection when his identity is revealed, and at a few points in between when “deity might have been broken.” Likewise, they show up in Acts at critical moments in the life of the fledgling church.

Ontologically perilous junctures.

They only show up in moments that matter for the End God has in mind.

They show up to steer the present towards the Future where Jesus lives with death behind him.

This is remarkable.

Because the Lord’s angels not only showed up that Christmas Eve on Summit Drive the night Will learned his father had died, they show up here, in this place, every Sunday, occasioned by bread and wine. The table attests to it: “Therefore we praise you, joining our voices with Angels and Archangels and with all the company of heaven, who for ever sing this hymn,” we say, “Holy, Holy, Holy Lord, God of power and might, heaven and earth are full of your glory.”

Ontologically perilous junctures.

And yet, here and now.

And always.

In other words—

God acts as though the whole universe is riding on placing himself in your hands and on your lips and you saying, “Amen. Thanks be to God.”

Share this post