Sunday is Pentecost, and as always we read from St. Luke’s sequel, the Book of Acts, where the disciples are back in the Upper Room where they’d been the night they betrayed him.

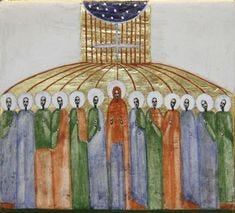

“And suddenly,” St. Luke says, there’s a sound— not like a still, small voice but a mighty rushing wind. And the Holy Spirit descends like fire, and people start speaking, and even though they’re speaking different languages there’s simultaneous translation.

All these different languages but everybody understands everybody. The Holy Spirit descends. And everybody starts speaking and everybody understands everybody.

The commotion gathers a crowd in the street, and the crowd starts to gripe: Those Christians are doing the same thing they did when Jesus was with them— they’ve been drinking (which, if you’re counting at home, is the first and last time anyone ever accused Christians of being fun).

Peter comes out to the crowd. And Peter speaks.

Remember where we left Peter in the story?

Back on the night they’d been in that same Upper Room:

“Jesus? Jesus who?”

The third time he actually curses Jesus’s name, which sounds worse when you translate the name the angel gave him:

“Jesus? Curse this Jesus whoever he is. Curse this savior.”

And then the cock crowed.

But on Pentecost they’re back in the Upper Room, and the Holy Spirit descends and Peter speaks. Peter says to the crowd:

“We’re not drunk— yet. We’ve still got an hour before brunch. No, no, no. All this your hearing, this is what the prophet foretold.”

And then Peter preaches this long sermon that crescendos with Peter proclaiming:

“This Jesus, whom you crucified, God has him raised from the dead [for our justification] and God has made him Lord. Be baptized.”

Let’s just get right down to it:

Why does the Holy Spirit come at Pentecost?

Make sure you’ve got my question straight. I’m not asking “Why does the Holy Spirit come?”

The Holy Spirit has already come.

Pentecost is not the arrival of a heretofore absent Spirit.

The Holy Spirit descended upon Jesus when he first preached. The Holy Spirit overshadowed his mother’s womb. Even before the incarnation, the Holy Spirit spoke to us by the prophets and, says Job, the Holy Spirit likewise enabled the understanding of those prophetic utterances.

But why does this instance of the Spirit’s occurrence, with fire and wind, come at Pentecost?

Or, as the Jews call it in Hebrew, Shavuot.

The Festival of Weeks.

Five weeks (penta-) after the Passover.

If Jesus sends the Holy Spirit to be with us in this in-between time between Christ’s first coming and his coming again, then why does the Holy Spirit not descend upon the disciples as they’re building make-shift tents of sticks and leaves to celebrate Sukkot, the Jewish festival that commemorated Israel’s wandering in the wilderness in between their rescue from captivity and their deliverance into a promised kingdom of God.

Why Shavuot? Why not Sukkot?

For that matter, Yom Kippur would make sense too.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tamed Cynic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.