Here is a sermon on John 18 for Christ the King Sunday at Zion Lutheran Church by my friend Dr. Ken Sundet Jones.

Grace to you and peace, my friends, from God our Father and our Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

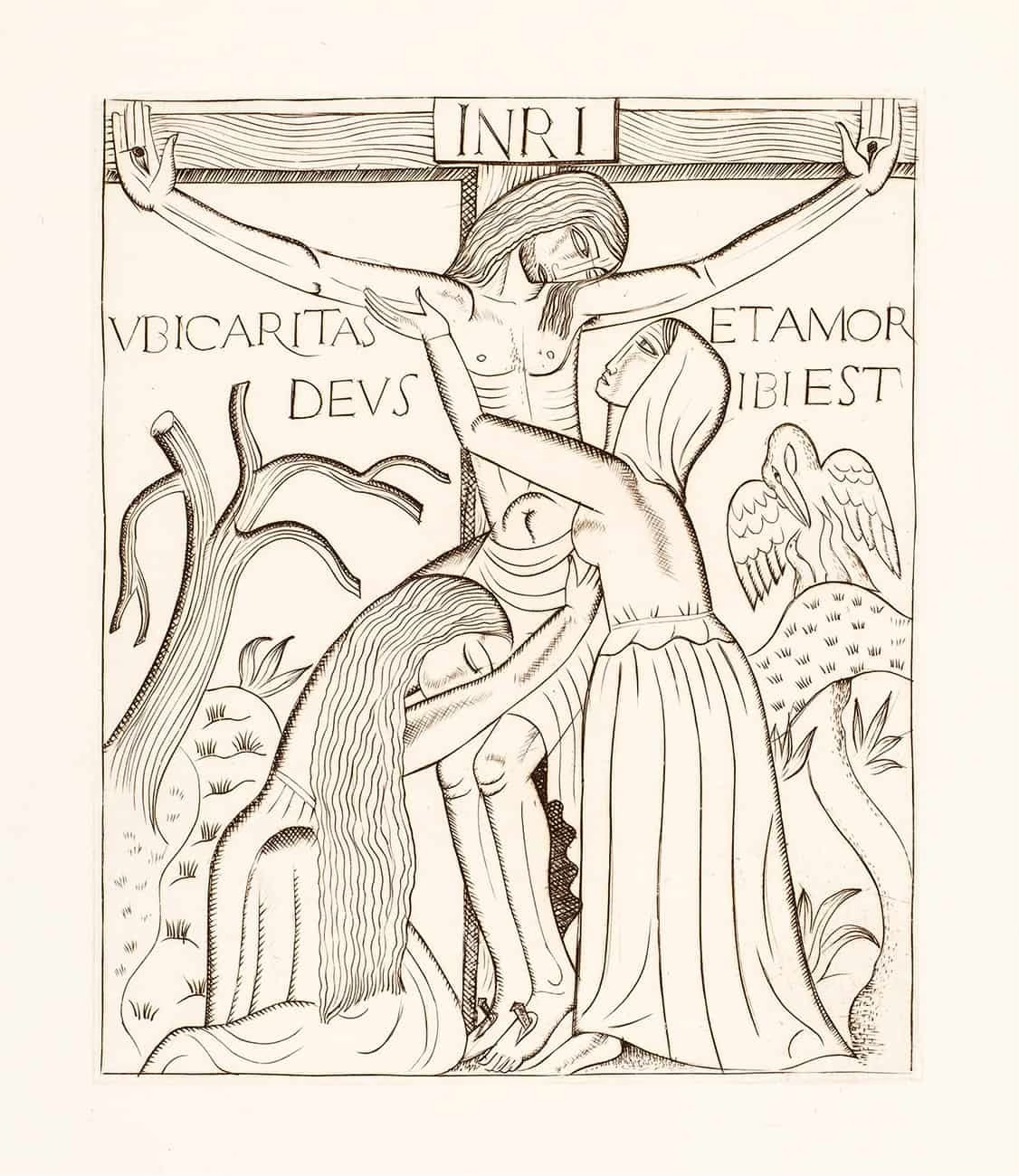

Today we come to the end of the lectionary year, our calendar of assigned worship readings from God’s Word. The year winds down, not like a child’s wind-up toy that slows with fewer, and fewer rotations until it finally dies, but instead goes out with a bang with this final festival Sunday. On Christ, the King Sunday, it’s appropriate to have Pontius Pilate’s interrogation of Jesus on the matter of the Lord’s sovereignty as our gospel reading.

We tend to think of Pontius Pilate as a fairly powerful person in first-century Judea. As governor of Judea, Pilate did have some power, after all, he was the representative of the Roman emperor (in this case, Tiberius Caesar) and commanded Roman forces, occupying the Judean territory. He could mint coins, and distribute funds. He collected taxes. And most importantly in the gospels, he had the authority to bring down a death sentence on any criminal. Jesus had been arrested at the behest of the religious leaders in Jerusalem and tried before them. Now he’d been brought to Pilate the governor for sentencing.

In the last week, my wife and I have discovered a television series on Max called My Cat from Hell in which a cat behaviorist does house calls with people whose feline pets are destroying their lives. One of the things he helps him understand (and that I have taken on with our own cat) is the importance of daily play with your cat. Cats, including our own beloved Lemon, are inveterate hunters. They love cat toys. We can tempt them with strings and feathers and fur that they can swat at and claw. Our cat grabs a fake bird on a string and believes she is toying it to death.

In our gospel story Pilate seems to believe he can toy with Jesus, that he can play around with this Jewish preacher, accused of seditious behavior, insurrection, and treason and have mastery over him. Pilate believes he wields some power over the Lord, and has some authority to determine his future. In his Gospel, the evangelist, John loves to recount these kinds of extended conversations with people like the Pharisee Nicodemus comes under cover of night or the oft-married Samaritan woman at the well. And every one of those conversations, Jesus is in control. The same is true here in Pilate’s palace. But where Nicodemus in the Samaritan woman are the beneficiaries of their chats with Jesus, here the Roman governor’s attempts to steer the conversation don’t give him what he seeks.

Pilate uses his sneering questions about Jesus’s kingship as bluster or even mockery. He knows, of course, as any governor of occupied territory would, about the background of this land, and the people Rome had subjugated. He would know about Jewish kings of the past and the people’s hopes for a new king. But Pilate can’t imagine such a king arising. Rome’s power, and hegemony, and geographical reach are too strong to think such an alternate future could ever be. Thus, he can order a sarcastic sign placed over Jesus‘s head on Golgotha reading Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum or “Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews. And in this story from John he can bat around unserious questions about kingship and truth.

Notice, though, how Jesus cedes no territory to Pilate. he doesn’t give an inch. Jesus, after all, is Lord of all from the foundation of the world. If Pilate knows the history of both Rome and Judea, Jesus knows the history of human nature, human power, and human sin. He knows how the arc of human experience bends. He is aware of the rise and fall of kings and empires. He knows the limits of personal autonomy and political posturing. Where Pilate believes in an everlasting and secure establishment of Roman power, Jesus knows the empire’s underbelly, and that of all human striving. And he is determined to do something about it.

Hamlet was right in Shakespeare’s play that there was something rotten in Denmark, and there’s something rotten at the core of the realm that Pontius Pilate administers on behalf of the emperor. But even if Judea had not been occupied by Rome and the zealots fighting for removal of Roman forces had had their way and were able to make Judea great again, Jesus is fully aware of how feckless Israel’s kings were and how faithless the people showed themselves to be. He was well aware of wars and rumors of wars, of Ahabs and Jezebels, and golden calves a-plenty in Jewish history.

From the very start in Genesis, where, in the beginning the earth was a formless void, a chaotic mass, and Jesus’s Spirit moved over the face of the deep, God has worked to bring order, safety, security, and peace where there was none. Even in the face of the destruction of Jerusalem, the razing of the temple, and the exile of the Israelites into enemy territory in Babylon, God had sought the salvation and redemption both of what he created and of the people he had chosen. Jesus, standing before the Roman governor is at the verge of all the strands of history coming together, and the hoped–for future being made secure. Jesus’s secure place as king, both before Pilate and for eternity at the right hand of God, as the one who, as the Apostles’ Creed declares, will come to judge heaven and earth, and as the wonderful counselor and prince of peace, who executes divine mercy, is the kind of proclamation that is especially important to hear any time chaos threatens to hold sway in our world.

That was true for a man named Charles Jennens in England in 1739. Jennens was a wealthy landowner, the owner of one of the best art collections in Britain, and a patron of musicians. In addition, Jennens suffered from what in his day they called the malady of melancholy. In other words, he regularly faced bouts of depression. The hopeless and endless gloom that clouds a person’s thinking in the midst of depression wasn’t helped by what Jennens saw in the world around him. In his lifetime he had experienced the beheading of his king, the takeover of England by the Puritans led by Cromwell, the restoration of the monarchy under Queen Anne whose reign and personality were shaky at best, and a knock-down-drag-out fight over her successor worse than our latest presidential campaign. The kingdom waged war against France, and the seas were rife with battles between the two countries’ navies. In Jennens’s day, a third of babies born in England died before they were 15. Pandemics of smallpox and outbreaks of cholera arrived with some frequency. English life expectancy was 36 years, which was higher than most other countries, but you couldn’t count on that if you were part of the under class, living in the slums of London, the greatest city on earth.

I’ve been reading a new history book titled Every Valley, in which Jennens plays a major role. The author Charles King describes what Jennens saw beyond his own fog under the noonday demon of depression. He says, “Jennens’s own outlook … was a ledger book of worries. By the time he reached adulthood, whatever opinions he held about the future arose from one unshakable conviction: that his life coincided with a wrong turn in national affairs and the initial stages of his country’s inevitable decline. On any street, in any town, the fetid churn of modern living was on ready display: men whittled down by politics and faction, country girls painting themselves into city courtesans, public executions, animals tortured for a laugh, wailing children abandoned to their fate. To anyone really paying attention, Jennens sometimes felt, the sum of public life — political conspiracies and scandals, economic scheming, one foreign war bleeding into the next, and all of it amplified by sensational reports in things that printers had recently named ‘News-papers’ — amounted to an ironclad argument in favor of despair.”

No matter where you stand politically, it probably sounds pretty familiar. And it’s entirely possible and completely reasonable in our current polarized and politically unstable culture that anyone would begin to feel hopeless. On top of that, it seems like there are forces in the world that have some pernicious glee over the hopelessness and disarray, and use it in their quest for some kind of empire that holds sway in the face of weakness, licentiousness, corruption, and way too many reality TV programs (My Cat from Hell included). How can anybody imagine a future of peace and security? Where is hope to be found?

King tells us what Jennens did in the face of his hopelessness and despair: “One troubled season, surrounded by what had become one of Britain’s finest repositories of human creativity, Jennens started pulling down books from his library shelves. He spent days poring over them, scribbling notes, filling up fresh sheets of paper with a sharpened quill. He copied down quotations from the sacred scriptures, some from the Psalms and the Hebrew prophets, some from New Testament epistles. He linked up one passage with another, editing and rearranging them, tying together themes that leaped out at him from the text — the whole of it not so much a story as an archaeology of ancient promises, dug up and dusted off for the present.”

Charles Jennens looked to Scripture’s promises of the anointed king, the meshiach in Hebrew and the christos in biblical Greek, who would make it all come round right. His string of Bible passages came to be known by that Hebrew word for anointed king. Jennens passed the list to a German composer who’d become a British citizen. The composer, now toward the end of his career and too worried about his own fortunes to pay it much attention, stuck the list of Bible passages in his chaotic filing system almost to be forgotten by the ages. But when the composer was pressed for time to write something for a commission to be performed in Dublin in less than three weeks, he pulled out Jennens’s hope-bestowing litany of verses about the anointed king who stood before Pilate as the longed-for Messiah.

The composer, of course, was George Frideric Handel, and his oratorio was Messiah. Handel, of course, rightly gets the praise, and you can’t look down on a guy who wrote the thing in less time than there is between now and Christmas. But I’d argue that it’s what Charles Jennens did in compiling his list of Bible passages for the sake of his own sanity and faith that is the reason Messiah is performed year after year by symphonies in large cities and sing-along community groups in small towns. Messiah is sublime music, but its text gives us something that is balm to our deepest longing.

The story of Jesus before Pilate is retold on Christ the King Sunday because it focuses on the question of kingship, that is, on whether there’s anyone we can look to for help in the face of the swirling chaos of our lives. Political promises to save democracy or to return our country to greatness are nice words, but their speakers have never had the power to make good on them. The shackled prisoner before the Roman governor in Jerusalem has strength and wiles that Pilate is unaware of. In just a few hours time Jesus’s last word from the cross will be “It is finished.” To the question “Will it all turn out right?”, Jesus’s response will be “Not for me, but for you I’ve got it all in hand. I’m gettin’ ‘er done.”

For all of us Charles Jennens types in the world, shaken by political events, knocked down by family dysfunction or financial blows, stricken by disease or aging, the Newtonian physics at play in an accident or the paralysis of watching TikTok videos when you should be productive, the declaration that the second person of the Trinity, Mary’s baby boy, and Pilate’s victim is king is both fighting words against the powers of chaos and the planting of hope. It’s because this king, your king, is the crucified and risen one who rules with both strength and mercy. All things are placed at his feet because he’s raised on a cross and pulled from a tomb.

And this day he tells you the truth Pilate asks after, the one little word from Luther’s Reformation hymn that wrenches not just his kingdom but you personally from those powers that seek to “take your house, goods, honor, child, or spouse.” Though life itself be wrenched away, God’s promise to you remains sure. It’s given on Calvary and sealed on Easter. In baptism you’re covered in it like a pile of mashed potatoes covered in the richest turkey gravy on Thanksgiving. In the bread and wine of the Lord’s Supper it comes as the fullest feast in the tiniest of comestibles. And week in, week out, you have a faithful pastor called and set apart as the Muscatine town crier for this king, sent to declare to you, “Hear ye! Hear ye! Your king is coming. Your warfare is accomplished. Hallelujah! And amen!” King? He’s more than king. He’s your king. Amen.

And now May the peace which far surpasses all our human understanding take your hearts and mind from the woes and ills of this world and keep them instead on the man before Pilate, your king, Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Thank you.

I can only hope this was recorded and maybe you can share?