"Work with your salvation in fear and trembling" is the better way to hear it

In all the present, as much as the past and the future, Christ is the protagonist of the salvation story

Philippians 2.5-11

Notice the formal pattern of the Christ Hymn, assigned for this Sunday’s Palm/Passion readings, with which the Apostle Paul pleads for unity in his embittered and divided congregation at Philippi.

The pattern of the hymn is threefold:

Election, Condescension, Exaltation.

Essentially, the pattern of the hymn is Up-Down-Up.

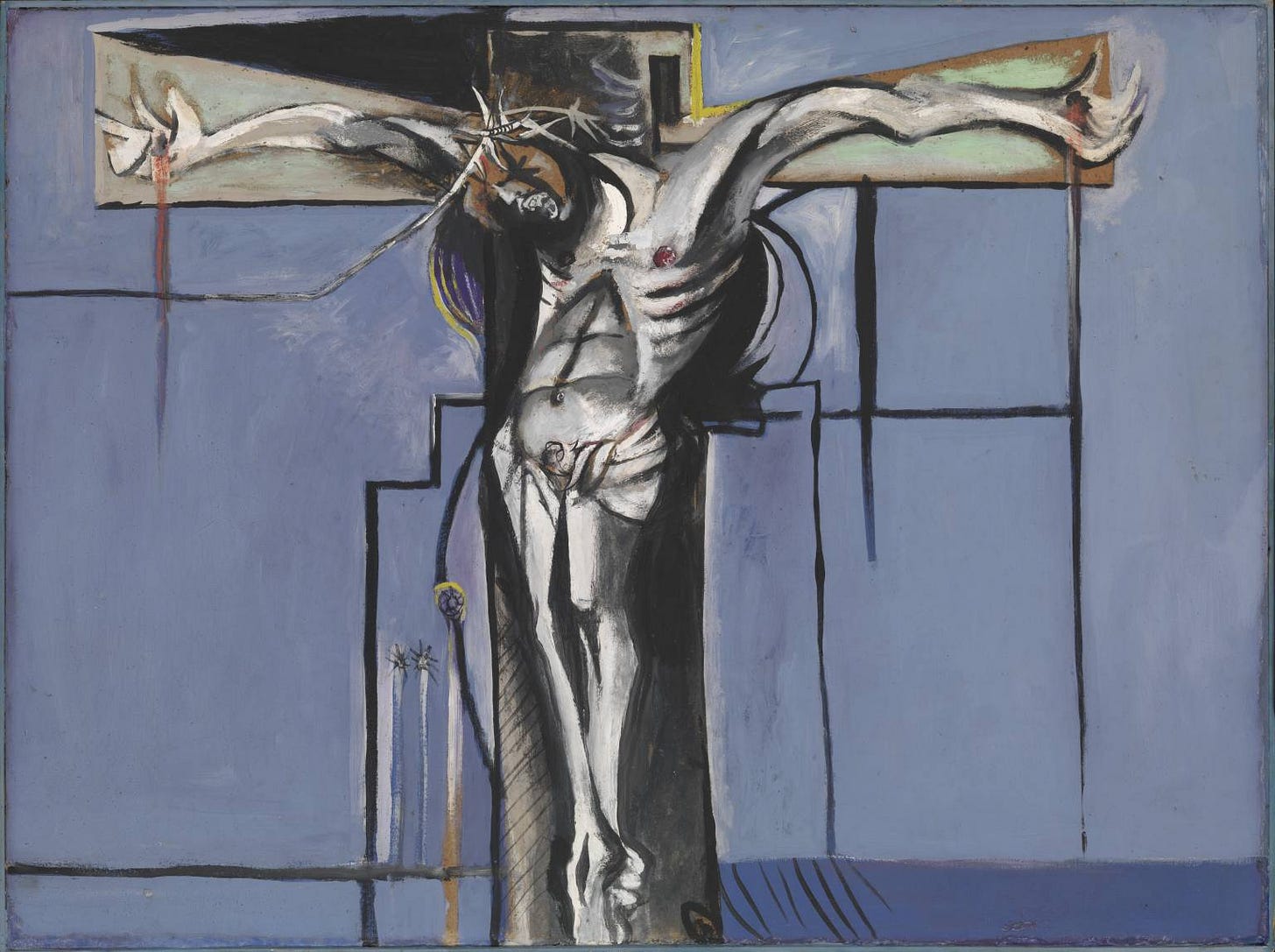

The Eternal Son is in the form of God and equal with God. The Eternal Son therefore is God, yet the Eternal Son elects to empty himself, sings the hymn. Veiled in flesh, our Lord conceals his majesty in the form of a slave, and by a “slave,” Paul means a slave of Sin and Death. That is, the One who, from dust, breathed into Adam the breath of life assumed the form of Adam. God, Luther said, loves to hide behind his opposite.

Up—Down—

“For us and for our salvation,” the Nicene Creed professes, the One through him all things were made, “came down from heaven…he became incarnate…and was made human.”

In the Crucified Son, our Lord shows himself to be an abolitionist. No matter what you may have heard about God loving us just the way we are, the Word of God bears witness that the Living God does not tolerate sin.

The Living God does not compromise with sin.

Unlike us, the Living God does not call evil “good.” Whatever under the forms of Sin and Death enters into conflict with can have no future with God. The “appointed means of their abolition” is the Crucified Son. By his obedience, Adam’s disobedience is revoked; by his death Adam’s death is undone; and by his submission to the cross, the condemnation of the primal sinner, and so of the whole human race, is reversed and overturned. As John Calvin notes of this today’s text, “Christ is much more powerful to save, than Adam was to destroy.” Or, as we sing at Christmas, he’s “born that man no more may die.”

Up— Down— Up—

After he completes his work of perfect obedience, the Crucified Son is vindicated by the Almighty Father. He is raised from the dead and returned to glory. The Eternal Son is returned to the Father as the Crucified Son where he is now and forever the Exalted Son.

Christ’s ascension is a sort of incarnation in reverse.

Just as the Eternal Son crosses over into Sin and Death without ceasing to be God, so now the Crucified Son crosses over from earth to heaven without ceasing to be human.

This is important—

The form the Son takes on earth, the form of a crucified slave, he takes that form with him to sit at the right hand of the Father. The Crucified Son brings his humanity with him into the very being of God. Which means, he brings you with him, in him, back to God. As Jesus said, “No one comes to the Father except by me… If truly you know me, you will know my Father as well.”

I draw your attention to the Up—Down—Up plotting of Paul’s Christ Hymn because just as it has a threefold pattern to it, so too, does the Apostle Paul use our text today to display the three different tenses of salvation.

The hymn has three movements—

Up—Down—Up.

The Eternal Son, the Crucified Son, and the Exalted Son.

Likewise, the Son’s work of salvation has three tenses—

Past, Present, and Future.

Salvation is not simply something lying on the horizon of the future the outcome of which is still up in the air. Salvation is not merely a finished and completed work, done by Jesus a long time ago in a Galilee far, far away that you only need accept.

On the contrary, salvation has three tenses.

The past tense, the future tense, and the present.

The Christ Hymn explicates the past and the future aspects of God’s work of salvation.

In the past tense, salvation is a finished and complete work without remainder. Indeed, this is the primary mode in which scripture speaks of salvation.

“Because the one man has died for all,” the Apostle Paul writes to the Corinthians, “all have died to sin.” Christ Jesus, our Great High Priest, has sat down, the preacher of Hebrews declares, for he has made a blood offering of himself, a perfect sacrifice— the sacrifice to end all sacrifices.

Salvation is past tense.

The Lamb of God, slain from before the foundation of the world, has taken away all the sins of the world. There is therefore now no condemnation, Paul rejoices in Romans 8. There is no condemnation on account of the merit of Christ’s perfect obedience to the point of death— even death on a cross.

Salvation is past tense.

It is finished, Jesus says, breathing his last.

Salvation has been accomplished for you, already, on Calvary. Even now, salvation has been realized, apart from you in Christ and done outside of you by Christ. Atonement has been made. Once for all. You are forgiven and free— “free of the record of debt that stood against you with its legal demands. Christ set it aside, nailing it to the cross,” Colossians says. For Christ’s sake, you have been justified— you have been reckoned with Christ’s own permanent perfect record. The wages of your sin have been paid with his death. You have been saved.

Karl Barth says the past tense of salvation is better understood as an “eternal perfect” tense in that the cross of Jesus Christ is a work in the past whose effects carry forward ceaselessly for others.

Salvation is already, but salvation is also not yet.

It’s future tense too.

Look again at the crescendo of Paul’s Christ Hymn.

The Crucified Son has been given the name that is above every name. The name that is above every name is the name first revealed to Moses from the Burning Bush. The name that is above every name is the divine name deemed too holy for Israel ever to utter it aloud.

However, the time is coming when even the rocks will cry out, praising Christ with that unutterable name.

Every knee will bow at its utterance, Paul writes, and every tongue will confess that Jesus is Lord. In fact, as the Apostle Paul makes clear in his Letter to the Romans, the future tense of salvation is cosmic in scope:

“The whole creation waits with eager longing…in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of God.”

Now, you don’t need a preacher to point out how it seems the whole of creation is still, as Paul puts it, groaning in labor pains. And certainly, there are more than a few who still have not taken a knee before Christ our Lord. Everywhere in the West we are told the Church is in decline and the Gospel is in retreat.

We can all feel the extent to which the “not yet” aspect of salvation abides.

It has a future tense. God will be all in all. What is already accomplished— the fact that you are in Christ Jesus, right now, your life hid with God— will one day be actualized in glory. What is already real because of Christ’s past and finished work— the forgiveness of all your sins and the gifting of Christ’s own righteousness— will be revealed upon his return.

But in the meantime, there’s the “meantime.”

There's a third tense, there’s the present tense.

My mentor and muse, the Reverend Fleming Rutledge, writes about attending a weekday Evening Prayer service in a large Episcopal parish while she was traveling on a preaching and speaking tour. The service of Evening Prayer was led by lay people, and it included, Fleming observes, a very instructive mistake.

During the service, an older woman came forward to read the scripture lesson. The woman looked like your archetypal Episcopalian: a White Anglo-Saxon Protestant, born and bred for propriety and rectitude, with, no doubt, a husband straight out of a John Updike novel. The scripture lesson that evening was our biblical text for today, a section of Chapter Two of Philippians. The woman came to verse thirteen, Fleming says, and with great solemnity began to read it:

"Work out your own salvation with fear and trembling ..." and then she stopped.

“She didn't just drift off,” Fleming notes, “as if she had lost her place or forgotten something. She came to a full stop deliberately, emphatically, at the comma, instead of the period. If she had shaken her finger at us, it couldn't have been more clear; it was an order from her to us. It was as if she were saying, "I've worked out my salvation, now you work out yours, and it had better be with plenty of fear and trembling!” It would have been funny if it hadn't also been so serious.”

Fleming writes that after the service was over, she crept up to the front of the sanctuary and took a peek on the massive lectern at the Bible from which the woman had read the scripture.

She wondered if perhaps the passage had been marked out incorrectly.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tamed Cynic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.