Revelation 4.1-11

On December 10, 1933, Karl Barth preached in the Schlosskirche at the center of the University of Bonn in Berlin where he was Professor of Theology. The Third Reich was only in its first year of power— elected power— but already the university, just like most of the church, had acquiesced to the racist demagoguery of an administration that had pledged to make Germany great again.

On that day in Advent, Barth stood in the university pulpit and, taking his text from Romans 15, he preached on our indebtedness as Christians to God’s primal and eternal choosing of his Israel. Halfway through his sermon, to a proud congregation who assumed they were on God’s side of history, Barth preached:

“Christ has received us, received us as a beggar is received off the street. We can even go so far as to say: we have been accepted, like an orphan is accepted into an orphanage. Christ sees us as Jews in conflict with the true God and as Gentiles living peacefully with the false gods, but he sees us both united as “children of the living God””

Christ sees us both, Barth said, quoting the prophet Hosea, united as “children of the living God.” Both races, both Christians and Jews— indeed, Jews before Christians— Christ sees us both the same, as children of the living God. Barth’s well-educated, ivory tower audience got the message. Many of them got up and walked out of the Schlosskirche right there in the middle of his sermon.

At one point, later in his sermon, Barth looked up from his manuscript and, as an aside, he lamented, “The suicides!” Everyone left in the pews knew to what Barth was referring. That year in Berlin, after the administration had quelled peaceful protests by police and military force, Germany had witnessed a rash of Jewish suicides. Karl Barth, who already had members of the Gestapo lurking in the back of his lecture hall, monitoring him, left the Schlosskirche that day in Advent, folded up his sermon manuscript, slid it into an envelope, and sent it off to Adolf Hitler.

Soon after, Barth was fired from his position and exiled back to his home in Switzerland.

Before his ouster, as soon as the university fell eagerly into the hands of the Nazis, Barth began teaching unofficial preaching classes. (Lectures later published as Homiletics.) Boredom and irrelevance in preaching can only be defeated by strict attentiveness and obedience to the biblical text, he said. “The only remedy for the bourgeois blather, urbane paganism, and sentimental nationalism that infects too many sermons was scripture.”1 The text liberates us from modern religion’s main preoccupation – ourselves– so that we can do the main business of the church, daring to listen to and talk about God.

Uniformed Nazis stood at the back of those lectures too, taking notes.

“I didn’t know that Herr Hitler had an interest in preaching,” Barth quipped jovially.

When the regime finally exiled Barth back to Switzerland, his students bid him a tearful farewell, in which they asked him for a benediction.

Famously, Barth responded, “Exegesis, exegesis, exegesis.” In other words, our only hope as the world hangs on the precipice is to preach “Jesus Christ is Lord” more stubbornly than ever before.

Those same students asked the departing Barth how they, as preachers, should respond to Hitler’s dictatorship. Barth’s surprising reply confounded them.

“Preach,” Barth insisted, “as if nothing happened.”

Preach as if nothing happened.

That is—

As a Christian, do not be fooled.

And as preachers, do not fool others.

The real world, what’s really going on in the world, the true state of reality— no matter what your eyes see or the headlines say— is that Jesus Christ is Lord.

“How can Adolf Hitler be a nothing?” Barth’s students wondered.

Clearly, they didn’t see whatever Barth had been shown.

And Barth warned them that the church must not allow its imagination to be captured by the world’s self-aggrandizing myths. We may resist injustice and condemn sin, of course, but in giving them our time we must not give the powers and principalities of this world inappropriate glory, honor, and dominion. We must not give to Caesar what belongs to God because Caesar’s days are numbered and the Kingdom is coming soon and, already, Jesus is Lord.

So preach as if nothing has happened.

That is—

Do not make the world’s darkness or our inveterate sinfulness more fascinating than the glad tidings that Jesus Christ lives with death behind him. The lordless powers of this world are merely provisional, passing away, dethroned by the cross and resurrection, though they haven’t yet gotten the news.

Of course, Barth conceded, Hitler’s dictatorship is a terrible “something,” but, Barth said, “the little man in Berlin is not the Lord of history.”

But to believe such a claim, to heed advice like “preach as if nothing happened,” it takes more than faith.

It requires revelation.

The old rabbis said of Israel’s scriptures that of all the books of the Bible the apocalyptic prophet Ezekiel “most pollutes the hands.” The rabbis meant that the Book of Ezekiel reveals a mystery so deep it can render the reader unfit for an ordinary world. By unveiling the knowledge of things hoped for, the prophet Ezekiel can leave his hearers fitting into time less comfortably than they did before coming into contact with him.

The same could be said of the Book of Revelation. The Apocalypse to John “most pollutes the hands” of those who come into contact it, not the least for this vision the Spirit of Jesus discloses, revealing how heaven intrudes upon the earth. As all things in creation are at once immediately available to God, the very throne of heaven was always right there, nearer to John on his prison island than his closest cell mate. In other words, the world’s reality has a dimension we cannot see unless we are shown. But once seen— and believed— it cannot be unseen.

Once unveiled, the vision is as stubborn and sure as a stain on your hands that refuses to wash out.

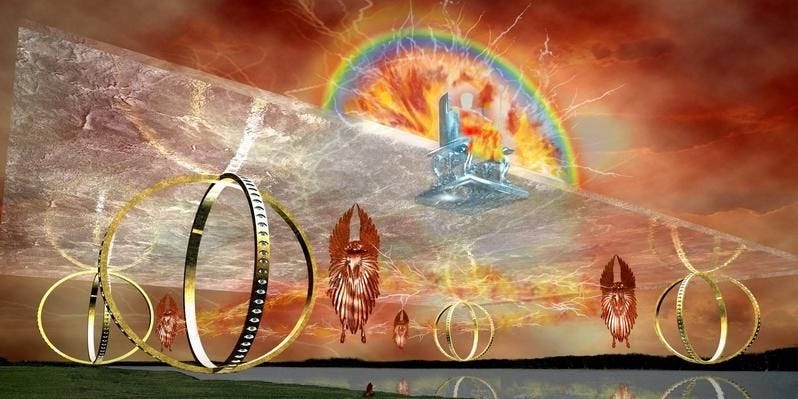

Revelation 4 ostensibly marks a shift from the “real world” to the place God makes for himself in creation, but even as the door to heaven is opened up and the Risen Christ speaks with the voice of a trumpet and the Spirit catches him up into a revelation, John’s feet remain planted firmly on Patmos. John sees the Merkahbah, the same cherubim throne shown to Ezekiel in exile with his people on the banks of the Chebar River in Babylon. Ezekiel saw above the throne “a figure with the appearance of a man” who “is the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord.” Sit with the remarkable mystery. According to Ezekiel’s own testimony to it, roughly six centuries before the annunciation, Ezekiel sees Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim seated above the throne of God by the rivers of Babylon.

This vision revealed to John most pollutes the hands of those who grasp it.

Where Ezekiel describes Jesus in terms of God’s kabod, John describes the same glory in terms of precious jewels, jasper and carnelian. Just as Ezekiel saw that the throne of God is itself alive, sentient as no crafted throne can be, John reports how spirit animates the throne. Energy flows centripetally around it in the form of a cosmic liturgy, and energy flows centrifugally from it in cracks of lightening and peals of thunder. In both visions, the seers also see the rainbow— the sign from Genesis that signifies both God’s covenant of peace to Noah and God’s requirement of justice for Noah.

It most pollutes the hands.

Twenty-four other thrones surround the heavenly throne on which sit the twenty-four elders, crowned and clothed in baptismal gowns and crying holy. God is jealous but God is not miserly; God rules with the twenty-four elders who are the twelve patriarchs of Israel and the twelve apostles of Israel’s servant, Jesus. The patriarchs and the apostles enthroned around the throne. Underneath the throne, John sees, is the sea— the scriptural symbol for chaos and dread— now made still and smooth as glass.

Heaven is the place God has made for himself in his creation.

Just so, heaven always intrudes upon the world.

Heaven’s throne is right there, as near to John as the lock on his prison bars.

That’s what John sees.

That’s the revelation.

Around the throne, on each side of the throne, John sees in Patmos what Ezekiel saw in Babylon. The living creatures. The first with a face like a lion. The second with a face like an ox. The third with a face like a human face. The fourth with a face like an eagle. According to the most ancient reading, dating all the way back to John’s own generation— take a look at the altar at the National Cathedral sometime and you’ll see— the four living creatures are the four evangelists of the gospels. Mark, Luke, Matthew, and John respectively. Their witness to the grace of God in Jesus Christ through cross and resurrection is what evokes the cosmic doxology that John hears when he sees:

“You are worthy, our Lord and God, to receive glory and honor and power, for you created all things, and by your will they existed and were created.”

Once it’s unveiled?

It pollutes the hands.

Paul says that unless we are shown the true nature of reality we can see only as through a glass dimly. Evidently, our hearing is likewise impaired. Otherwise, surely John would’ve already heard the elders’s unceasing singing.

After all, the one detail John omits, the one item he does not report from this unveiling, is any kind of journey whereby he’s transported from earth to heaven.

Just like Ezekiel by the rivers of Babylon, he is exactly where he was.

Thus, all along, the very gate of heaven was no further from him than he was to himself.

Reality has a dimension we cannot see unless we are shown.

But once you see it, you cannot get it off your hands.

Some time after Karl Barth had been exiled and after the war had been ended, the American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr sharply criticized Barth for failing to condemn Soviet communism.

Not one to flinch from a fight, Barth responded to Niebuhr that the Soviet project might be premised on a dangerous naïveté and it would, no doubt, prove a short-lived phenomenon but, Barth pointed out, communism’s critiques of American capitalism were nonetheless biblically warranted critiques. Besides, Barth argued, America’s self-attested, city-on-a-hill exceptionalism could very well be a greater insult to God’s glory than Russian communism. Hence, when Barth visited America for the first and only time toward the end of his life, his face having just graced the cover of Time, he made a point to visit American prisons. Throughout his career, Barth had regularly preached behind the bars of Basel’s prison. Visiting captives in America, Barth rudely, boldly noted the nasty similarity between democracy’s prisons and communism’s gulags.

Once again, Barth provoked complaint for his failure to comment on the Red Scare. But Barth only replied that he refused to be jerked around by what the world regarded as momentous issues or earth-shaking events. Barth said:

“Our greatest challenge is to deal with the shock that God has, in Jesus Christ, made our history God’s.”

That reality is the truer reality to which we should give our time and attention.

God has made our history God’s history. Just so, God has made our lives God’s life. God has made your life God’s own life. Reality, therefore, has a dimension we cannot see unless we are shown.

The Spirit of Jesus shows to John the very same throne— the Merkahbah— that the prophet Ezekiel saw. Presumably, details that only one of the two prophets describes the other prophet nevertheless witnessed. It’s the same throne. For instance, Ezekiel makes no mention of the two dozen thrones that encircle God’s throne, yet, because it is the same throne, we may conclude that Ezekiel nonetheless saw them.

Likewise, John does not include an attribute of heaven’s throne that is as vital as it is strange.

Wheels.

Heaven has wheels:

“Now as I looked at the living creatures, behold, there was one wheel on the ground beside the living creatures, for each of the four of them. The appearance of the wheels and their workmanship was like sparkling topaz, and all four of them had the same form, their appearance and workmanship being as if one wheel were within another. Whenever they moved, they moved in any of their four directions without turning as they moved. As for their rims, they were high and awesome, and the rims of all four of them were covered with eyes all around. Whenever the living beings moved, the wheels moved with them. And whenever the living beings rose from the earth, the wheels rose also. Wherever the spirit was about to go, they would go in that direction. And the wheels rose just as they did; for the spirit of the living beings was in the wheels. Whenever those went, they went; and whenever those stopped, they stopped. And whenever those rose from the earth, the wheels rose just as they did; for the spirit of the living beings was in the wheels. Now over the heads of the living beings there was something like an expanse, like the awesome gleam of crystal, spread out over their heads.”

— Ezekiel 1.15-22

This is not merely a vital detail.

It’s gospel.

Ezekiel makes it plain that however astonishing their appearance and however preternatural their capabilities, they remain wheels and— Ezekiel insists— they are rolling on the earth.

Ezekiel sees the same Babylonian dirt under the throne’s wheels as he feels beneath his feet.

Just so, John saw the same soil of Patmos beneath the wheels as he felt under his own feet.

Heaven has wheels. Heaven’s like a food truck or an Amazon delivery van or Barbie’s pink convertible.

Heaven’s exactly like the Knight Bus in Harry Potter— not always seen perhaps but always available and every present.

This is not merely a strange detail.

It’s the sort of gospel you can’t get off your hands.

As Robert Jenson writes:

The division between heaven and earth, between cosmic reality and everyday reality, between the Kingdom and the world, between the Future and the present, between God’s life and our history, such divisions thus become radically problematic.

Heaven rolls along Babylonian earth.

Heaven travels on the soil of a penal colony off the coast of Asia Minor.

Like something out of the rap song “Ridin’ Rims.”

Visions are not dreams; they require the hand of the Lord. They inform about reality not the prophet’s inner reality. They are a looking at something. And, as a consequence, we who are their progeny see a reality inhabited by those who do not so see.

What do John and Ezekiel see?

And what can we see because they have been shown?

Just like Ezekiel before him, John sees God coming to judge and to save whilst in a place he might well have thought neither judgment nor salvation could reach. Neither Babylon nor Patmos are beyond the possibility of the Lord’s presence with his people. No place in the world is too far off and no situation in your life is too forsaken for the Lord to be with you and so for you.

God is not nowhere in the world.

This is what both seers see.

God is not nowhere in the world.

He’s on the move.

Rolling along.

Heaven has wheels.

The Spirit of Jesus says to both Ezekiel and John that what he unveils to the two prophets is “what must take place after this.” That is, the vision is a promise of the future. And because the vision is a promise from God, the promise is irrevocably unconditional. Therefore, the vision is gospel.

The vision is gospel.

On the basis of this vision, I can speak for God.

And I can make a promise to you.

Thus—

No matter how far off you’ve wandered, no matter how forsaken your situation appears, no matter how hopeless things seem, no matter how trapped and alone you feel, the Lord is on his way to you. Indeed he’s already closer to you than you perceive.

Will Campbell was a white Mississippi Baptist preacher and activist during the Civil Rights movement. He provoked bipartisan offense for his gospel-centered insistence on ministering to both Klansmen and their black victims. Speaking at a conference on the theme of Christianity and politics, a participant asked Campbell what he thought to be “the most significant thing going on in Washington these days.”

Will Campbell’s answer was blunt, offering just a glimpse at what we’ve been shown. Sounding like Karl Barth, Campbell said:

“There is nothing significant going on in Washington these days.”

After all, what’s so special about a stationary city on the Potomac when the Maker of Heaven and Earth is on the move in his own living motorcade?

It most pollutes the hands.

Wheels within wheels.

Jewels and white garments.

Crowns and a sea like crystal.

Six wings each and the unceasing sound of praise.

Eyes upon eyes upon eyes upon eyes.

The details are overwhelming and often inscrutable.

And yet—

All the details Ezekiel and John describe serve the restraint— the reverent reticence— you would expect from two Jews bound by the law, particularly the commandment, “You shall make no images of God.” In revealing what was shown to them, both prophets practice a still veiled unveiling. For John to reveal, for example, that the Risen Jesus appears like jewels, jasper and carnelian, is a faithful way to avoid reporting exactly what he saw and thereby making a graven image (in your mind) of God. Likewise, Ezekiel, seeing the same vision of the Risen Christ, builds in two intermediating qualifiers. Ezekiel relays that the one seated above heaven’s throne has “the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord.”

What Ezekiel and John say about what they saw is also a strategy of reverent silence.

They say what they say so as not to say— exactly— what they saw.

Which is to say, this vision of God in Revelation 4, this theophany of the Almighty’s motorcade with all its profuse particulars, it is not as concrete and definitive as the loaf and the cup on the table.

For just as this is God’s word for you this day, God says it straightforwardly, without any qualifying intermediaries, “This is my body broken for you. This is my blood poured out for you and for many for the forgiveness of sins.”

This theophany is a promise.

The Lord is more than on his way to you. He’s already here. He wants more than to pollute your hands. He wants himself to be placed in them.

Willimon, A Unique Time of God?

Share this post