Genesis 25.27-34

“What then are we to say about these things?” the Apostle Paul writes at the crest of his epistle to the Romans. “If God is for us, who is against us?” Paul asks the church at Rome. For Paul, it’s not a rhetorical question. For Paul, it’s a question at the beating heart of the Bible.

If God is for us— all of us— if God is determined to reconcile and redeem all of us, then what could stand in God’s way? “What can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord?” the apostle asks. And then, one by one, Paul proceeds to eliminate the possibilities:

Hardship. Check.

Injustice. Check.

Persecution. Famine. Check. Check.

Nakedness. Nope.

War. Not it either.

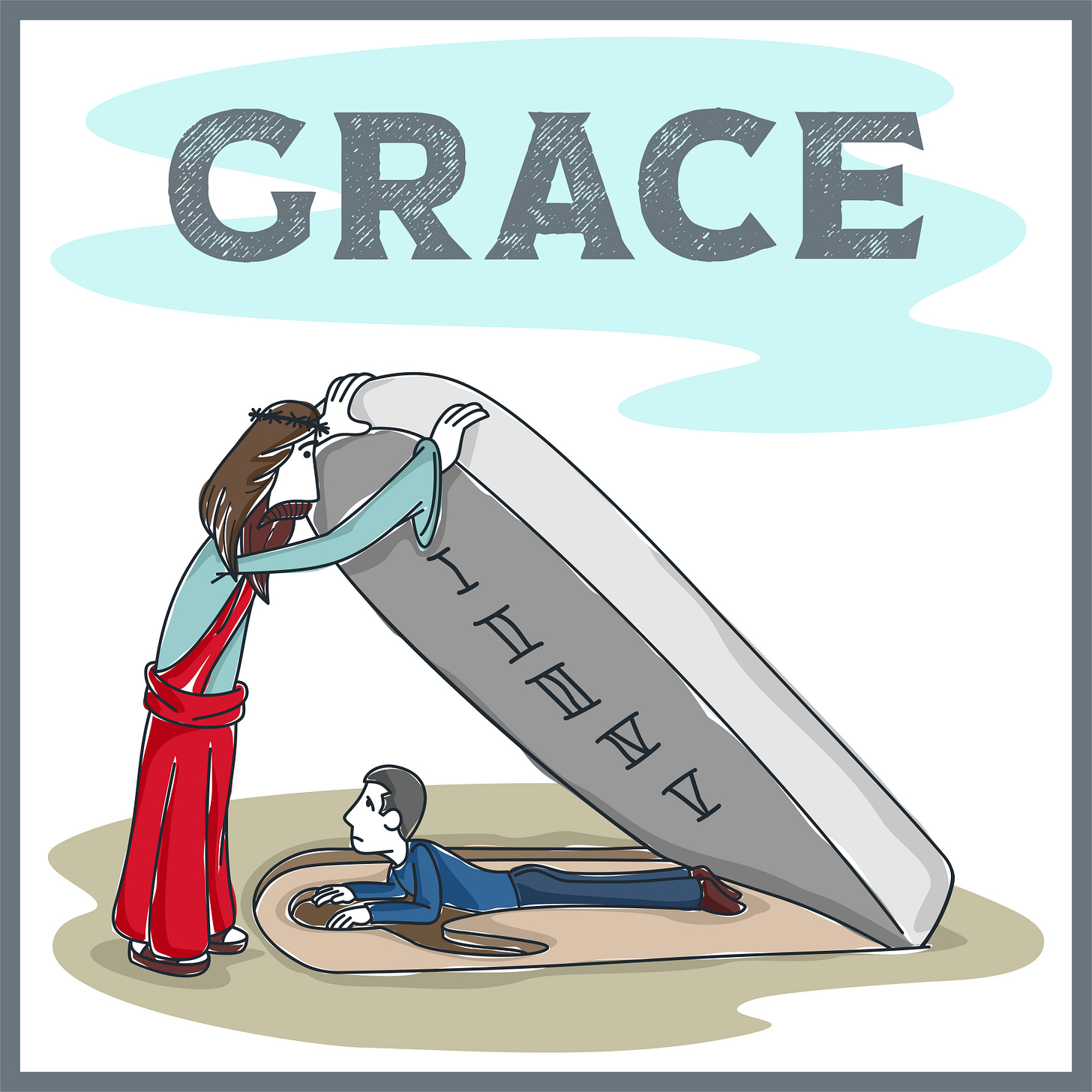

What then, in the end, can separate us from God? Not Death. Not Rulers. Not Powers. Neither things present nor things to come. Not anything in all of creation. NOTHING can separate us from what God wants to do with us. Except, the Apostle Paul does leave one possibility off his list; see if you can spot it:

Hardship

Injustice

Persecution

Famine

Nakedness

Peril

War

Death

Rulers

Powers

Notice there is one possibility missing from Paul’s list, one potential dis-qualifier lingers still.

You.

Can you finally separate yourself from the love of God?

Can I?

Have we been made with the ability to sever ourselves forever from the love of our Maker?

If Injustice and Persecution and War can’t leave our ledgers permanently in the red, can our Refusal?

Back in the day, when I worked as a chaplain at Trenton State Prison in New Jersey, part of my routine, every week, was to visit the inmates in solitary confinement. It was a sticky, hot, dark wing of the prison. Because every inmate was locked behind a heavy, steel door with just a sliver of thick plexiglass for a window, unlike the rest of the prison, the solitary wing was as silent as a tomb.

Whenever I visited solitary, the officer on duty was almost always a fifty-something Sergeant named Moore. Officer Moore had a thick, Mike Ditka mustache and coarse sandy hair he combed into a meticulous, greased part. He was tall and strong and, to be honest, intimidating. He had a Marine Corps tattoo on one forearm and a heart with a woman’s name on the other arm.

The Old Adam in me would described Officer Moore as an asshole.

Whenever I visited solitary he’d buzz me inside only after I refused to go away. He’d usually be sitting down, gripping the sides of his desk, reading a newspaper. I hated going there because, every time I did, he’d greet me heated ridicule. He’d grumble things like, “Save your breath, preacher, you’re wasting your time.” He’d grumble things like, “Do you know what these people did? They don’t deserve forgiveness.” He’d grumble things like, "They only listen to you because they’ve got no one else.”

“No, they’ve got someone other than me,” I’d tell him, “That’s why I’m here.”

Once, when we gathered for worship, I’d invited Officer Moore to join us. He grumbled that he’d have “nothing to do with a God who’d have anything to do with trash like them” and he refused to come into the service. He sat outside instead with his arm crossed. The locked prison door between us.

About halfway through my time at the prison, Officer Moore suffered a near fatal heart attack; in fact, he was dead for several minutes before the rescue squad revived him. I know this because when he returned to work, he told me. He tried to throw it in my face.

“It’s all a sham,” he grumbled at me one afternoon.

“I was dead for three minutes. Dead. And you know what I experienced? Nada. Absolutely nothing. I didn’t see any bright light at the end of any tunnel. It was just darkness. Your god? All make believe.”

“Bless your heart," I thought.

"Maybe you should take that as a warning,” I said, “Maybe there’s no light at the end of the tunnel for you.”

He grumbled and said, “Don’t tell me you, Mr. Grace and Forgiveness, believes in hell?”

“What makes you think I wouldn’t believe in hell?” I asked.

“Oh, and since I don’t believe in your Jesus, I’m going to hell? Is that it?”

Officer Moore pushed his chair back and fussed with his collar.

He suddenly seemed uncomfortable. His eyes took a bead on me.

“So what the hell is hell like then?’ he asked, smirking, “Fire and brimstone, I mean, really?”

“No,” I said, “fire, brimstone, gnashing of teeth, those are probably all metaphors.”

He let out a sarcastic sigh of relief.

So then I added, “They’re probably metaphors for something much worse."

That got his attention.

“Your loving God sends people to a place worse than brimstone just because they don’t believe in him?" he asked.

“Who said anything about God sending them there?” I replied, “No, I think hell is like a prison where the door is locked from the inside.”

He looked at me, suddenly no longer with contempt.

“It’s like C.S. Lewis said,” I told him, “In the end, there are only two kinds of people: those who say to God, “Your will be done,” and those to whom God says, “Your will be done.”

But, I wonder. Is that right? Is it even possible? Do sinners possess the stubborn strength to fight God to an everlasting draw? Can we separate us ourselves from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord?

On the one hand, it appears we are able.

After all, scripture is unwavering in the sole qualification for salvation.

“Christ is the end of the law of righteousness,” the Bible says, “for everyone who believes.” “If you confess with your mouth that Jesus Christ is Lord,” says scripture, “and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.” The bar is the same in the Old Testament too. The Book of Joel says quite clearly, “Everyone who calls on the name of the Lord [in faith] will be saved.”

Can we separate us ourselves from the love of God? On the hand, it certainly seems so, for unfaith abounds.

On the other hand, though, Paul insists that the word of God cannot fail.

“My word will not return to me void,” the Lord tells the prophet Isaiah. The word of God can only work what it says, do what it decrees, accomplish what it announces. And the word says clearly, the Lord’s not content with just you and you and you. God wants all of you.

For the apostle Paul, this question is no theological abstraction. The reason that famous passage in Romans is so impassioned is because Paul is agonizing over the fact of Israel’s unfaith. The God of Israel has raised his eternal Son from the dead, yet the Israel of God believes not these tidings.

“Does this mean God has rejected his people?” Paul asks at the top of Romans 11. The grammar of the question gives away the answer. As soon as Paul refers to Israel as God’s possession he’s already shown his tell. “By no means!” Paul answers immediately. After all, God made a promise, “I will be your God and you will be my People.” And if God can break his no-strings-attached, unconditional, promise, then God is the very troubling answer to the question,

“What can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord?”

Does this mean God rejects those who do not believe?

By no means!

For all the ink Paul spills in his anguish, the problem can be put rather simply:

God desires all to reciprocate his love and mercy— made flesh in Jesus Christ— with faith, alone.

Many— but especially the Israel of God— do not so believe.

Finally— here’s the kicker— God’s word can no more fail than God’s promise can be broken.

In wrestling with this sorrowful conundrum, Paul looks to the past and there he discovers a pattern that enables him to predict a hopeful future. Specifically, Paul considers the twin sons of Rebekah (you were wondering when I was going to get around to our text). Jacob attempted to swindle his older brother at a moment of acute vulnerability while Esau foolishly was willing to forsake his entire inheritance in order to satisfy his appetite.

Neither of Rebekah’s children prove exemplary; nevertheless, both Jacob and Esau are chosen by God while they’re still in Rebekah’s womb. God’s election happens in utero. The promise was spoken to Rebekah, Paul writes of Jacob and Esau:

“though they were not yet born and had done nothing either good or bad— in order that God’s purpose of election might continue, not because of works but because of him who calls— Rebekah was told, “The older shall serve the younger…” So then it [the purpose of election] depends not on human will or exertion, but on God who has mercy.”

As Paul dwells on his fellow Jews’s apparent rejection by God, Paul sees a pattern behind the way God has worked in the past, election and rejection.

Abel over Cain.

Sarah instead of Hagar.

Moses against Pharaoh.

David to the exclusion of Saul.

Israel rather than any other nation of the earth.

In each and every case, God’s choosing “neither corresponds to nor is contingent upon prior human difference.”

Jacob and Esau are twins.

There is no difference between them—that’s precisely the point!

God’s choice creates the difference.

God elects for the promise to go through Jacob not Esau, and God elects Jacob not Esau before either Jacob or Esau could do any bad or any good. Therefore it is a choice God makes irrespective of merit or demerit. It’s a choice premised on the providence of God not on the performance of either Jacob or Esau.

What’s more, Paul notices that this pattern of election and rejection, faith in some and hardness of heart in others, is an inextricable part of the history God makes with his world. What looks like God’s rejection of some in scripture always serves God’s redemption of the whole. The Father seemingly rejecting the Son, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” even that forsaking is for all.

Hope is the child of history.

Paul’s hope for the future, his hope for those who do not believe, is a child of this history, election and rejection. “Has the Israel of God stumbled so as to fall away forever?” Paul asks before he answers in the very same breath, “No!” Instead Israel’s unfaith, what appears to be God’s rejection of them, it is a choice God has made for the reconciliation of the whole world, Paul says. “For God has consigned all to disobedience [the Gentiles’s their ungodliness, the Jews’s their unfaith],” Paul writes, “so that he may have mercy on all.”

God has consigned some to unbelief; so that, God may have mercy on all.

The failure of some to believe is, in fact, the means by which God is working even now to show mercy to all.

In other words— pardon the cliche— it’s all a part of God’s plan.

God’s predestination.

It’s not surprising that Paul concludes Romans 9-11 with God’s plan. Paul began with predestination too. Just before Paul wonders, “If God is for us, who can be against us?” Paul reminds us that those whom God predestines— the whole world— God calls. Those whom God has chosen according to his plan (ie, all of us) God calls, and God calls— specifically— with his justifying word (ie, the Gospel).

That’s Romans. Chapter eight. Verse thirty.

That’s the word of God.

Predestination.

It’s not a primordial choice that makes you no more than a bit of code in the Almighty’s matrix. It’s a present-tense call. That is, God applies his predestination in the here and now through the handing over of the goods of the Gospel.

Like Jacob and Esau, God makes choices.

God has consigned some to unfaith.

Why?

So that, those who do not believe might be summoned into faith by the handing over of the goods.

By you.

By Christ’s own word on the lips of the likes of you.

As scripture says plainly, “faith [which saves] comes from hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ.”

Predestination is not abstract.

It’s auditory.

Predestination is not speculative.

It’s spoken.

The God of an idea, like universalism, that says “God loves everybody,” such a God never gets around actually to saying it to anyone.

The God of predestination, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, wants to say to everyone, a creature at a time, “I love you. I forgive you. You’re mine.”

Is that clear, I wonder? Predestination isn’t a divine decision that hovers a thousand miles above us and a billion years behind us. Predestination happens, here and now, in the gospel word on the lips of a sinner to another sinner.

As Paul writes to the Corinthians, “For it pleases God to save…”

How?

“It pleases God to save through the folly of proclamation,” Paul says.

In other words, it please God to save the whole world through such foolishness as you and your words.

A couple of months ago, Betsy shared with me how a stranger wandered into the Mission Center one afternoon while she was there sorting food. He’d walked there, for two hours, all the way from the other side of Woodson High School. He wanted— he needed, he said— to confess his sins.

Betsy says she was reticent at first, “I’m not a pastor. There’s no preacher or priest here. Maybe if you call and schedule…”

The stranger was undeterred, “I need to confess.”

So Betsy relented and said, “Alright, I’ll listen to you.”

And this stranger spilled out into her ear his secret burdens and his most troublesome sins. After he was finished, Betsy says, he peered up at her expectantly.

“Does this mean I’m forgiven? Does God forgive me?”

And Betsy says she replied, “Well, I’m not sure. Who am I to say whether or not God forgives you?”

When Betsy told me how she had answered the stranger— we were standing on the church steps after worship one Sunday— I initially responded pastorally, “Betsy! No!”

“I should’ve told him he’s forgiven? But I’m not a pastor…”

“You’re baptized, Betsy,” I may have said a little loudly, “You’ve been called to put just such a word in the ear of any person God sends your way.”

Now, it’s not Betsy’s fault.

She hadn’t yet heard this sermon.

The rest of you, however, will be without any excuse because you’re about to hear me announce that you have been called.

You have been called.

What do you mean I’ve been called? I was just a baby when I was baptized!

So what? Jacob was even tinier.

The Lord God desires to save all. And the Lord God has elected to show mercy upon all through those whom he has called. And just as surely as God chose Jacob over Esau, he has consigned some to unbelief so that unbelievers might hear God say— hear God on your lips say, “I love you. I forgive you. You’re mine.”

By virtue of your baptism, you have been called to a particular, peculiar task.

The baptized are authorized to do the mighty acts of God’s predestination. Your baptism commissions you, therefore, to speak not about God. Talk about God never comforted any conscience. Talk about God has yet to save a single soul.

Your baptism authorizes you to speak not about God but for God. God wants to hide on your lips in a word like, “Your sins are forgiven” or “Christ Jesus will raise you from the dead” or “The Devil has no power over you because Christ Jesus has saved you.”

God wants to hide on your lips in the promises he’s given us.

So, the next time it happens to you you’re without any excuse. You have been called to speak for God, to apply his predestination in the present. And if you’re dubious that you’ve been called, baptism notwithstanding, I can remove all grounds for doubt right this very moment, “In the name of Christ Jesus, I summon you to speak for him.”

There.

You’ve just been called again by God.

You see how it works?

The Holy Spirit lives in the promises he’s given us to speak.

The purpose of the doctrine of predestination is not speculation.

The purpose of the doctrine of predestination is proclamation.

The purpose of the doctrine of predestination is to give you a platform on which you can stand. It’s to give you certainty. It’s to give you an actual message, a concrete promise to deliver, because, by the doctrine of predestination, you can know without any doubt that if someone comes to you with unfaith, if someone comes to you burdened by their sins and regrets, if someone comes to you fearful of death or feeling forsaken by God, then it’s because the Lord God has sent them to you.

The Lord God has sent them to you— you, whom he has called to speak for him. God has chosen them and sent them to you. This is how God’s plan plays out. It’s not how I’d plan the salvation of the whole world, but give the Big Guy credit.He himself calls it folly.

Therefore—

When God sends someone like this to you, you don’t speculate.

Well, I think God probably forgives you. I guess we’ll see.

When God sends someone like this to you, you don’t settle for empathy, which is easier.

I’m here for you. You’ll be in my prayers. This is what worked for me.

When God sends someone like this to you, you don’t make appeals or exhortations. Give it over to God. Pray on it. Invite Christ into your heart. Repent and believe.

No, no, no.

You hand over the goods.

The Lord God in his predestination has set this creature before you. In that very moment. You don’t invite them to church next Sunday or entreat them to read their Bible or encourage them to talk to a pastor.

No, you’ve been called. You proclaim to them. You speak a promise over them. You deliver a promise that scripture authorizes you to promise.

I’m absolutely serious.

You can say— you must say— to the person burdened by shame or sin, “The Lord has chosen you and sent you to me so that I can say to you, “In the name of Jesus Christ, all your sins are forgiven.”

You promise the loved one who’s fearful and dying, “The next voice you hear will be the voice of Jesus Christ calling you, like Lazarus, straight out of your grave.”

To the person feeling forsaken by God, you say, “You were bought with a price. You belong to Christ Jesus. He’s got you. And he’ll never let you go.”

Every other time I went to the solitary unit at Trenton State, as always, Officer Moore would balk at buzzing me inside. He’d grouse about how I was wasting my time with “these losers,” and he’d snarl about how the gospel is so much foolishness. “A whole lot of nonsense,” he’d grumble, inspecting for contraband the bibles I’d brought with me. In the words of Paul, he remained “consigned to disobedience.” Locked up in unbelief.

Because I’d never bothered to use the keys Christ had given me. Officer Moore’s unfaith is on me. It’s my fault.

The trouble with thinking predestination is a divine decision that hovers a thousand miles above us and a billion years behind us is that it lets us off the hook.

It leaves no place for proclamation.

I sometimes spoke with Officer Moore about God but I never ponied up and spoke for God. I never dared to wave away his unbelief and say to him straight-up, “Christ Jesus has sent me to you to summon you to faith in him. Trust and believe.”

Can anything separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord?

As it turns, the “No” depends on you daring to do what he redeemed you to do.

Which makes it all the more imperative that I remind you that Christ is the host of this table.

Christ is here to give himself to you, not just in words but in wine and bread, so that you will take him at his word when he says to you, “I love you. I forgive you. You are mine.”

Share this post