Luke 10

This is not an attempt to pile on the new vice president, chase news-related clicks, or presume a prophetic posture. It’s just a sermon from the vault, from this month at the start of Trump’s first term.

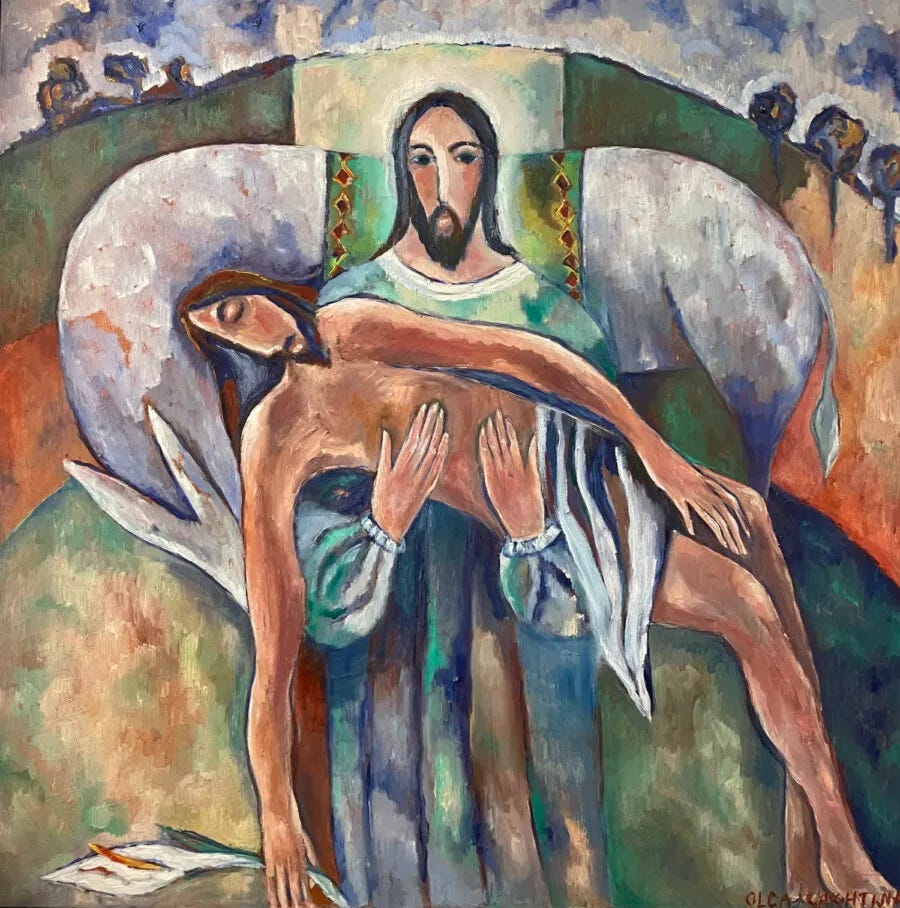

Many of have rightly critiqued JD Vance’s grasp of Christianity’s ethic of love for the neighbor; however, much of the pushback has deployed Jesus’ Parable of the Good Samaritan in a moralistic fashion— Jesus did not need to be crucified for such interpretations.

Neither Vance nor his critics seem aware of the parable’s actual offense. “Love your family first” does not land a cross on your back. We killed Jesus for telling stories like the one about the Samaritan.

Here is the sermon…

In front of a crowd of 70 or 140— who's to say how big the crowd really was— this lawyer tries to trap Jesus by turning the scriptures against him.

“Who is my neighbor?” the lawyer presses.

It's the kind of Bible question they could have debated for weeks. Read one part of Leviticus and God's policy is Israel First.

Your neighbor is just your fellow Jew.

Read another part of Leviticus and your neighbor includes the immigrants and refugees in your land.

Turn to another Bible passage, and the aliens who count as your neighbor might really only include those who've converted to your faith. Your neighbors might really only be the people who believe like you believe.

Read the right Psalms, and neighbor definitely does not include your enemies. It's naive, sing those Psalms, to suppose your enemies are anything other than dangerous.

So they could have sat around and debated on Facebook all week, which is probably why Jesus resorts to a story instead, about a man who gets mule-jacked, making the 17-mile trek from Jerusalem down to Jericho, and who's left for dead, naked in a ditch on the side of the road.

A priest and a Levite respond to the man in need with only two verbs to their credit.

See.

Pass by.

But, like State Farm, it's a Samaritan who's there for the man in the ditch. Jesus credits him with a whopping 14 verbs to the priest's puny two verbs. The Samaritan comes near the man, sees him, is moved by him, goes to him, bandages him, pours oil and wine on him, puts the man on his animal, brings him to an inn, takes care of him, takes out his money, gives it, asks the innkeeper to take care of him, says he'll return and repay anything else.

14 verbs.

Fourteen verbs is the sum that equals the solution to Jesus' table-turning question, “Which man became a neighbor?”

Not only do you know this parable by heart, you know what to expect when you hear a sermon on the Good Samaritan, don't you? You expect me to wind my way to the point that correct answers are not as important as compassionate actions. That Bible study is not the way to heaven, but Bible-doing. Show of hands, how many of you would expect a sermon on this parable to segue into some real-life example of me or someone I know taking a risk, sacrificing time, giving away money to help someone in need.

How many of you would expect that?

Right. I know how many of you all would expect me to try to connect the world of the Bible with the real world by telling you an anecdote?

An anecdote like, on Friday morning…

I drove to Starbucks to work on a sermon. As I got out of my car standing in front of Starbucks, I saw this guy standing in the cold. I could tell from the embarrassed look on his face and the hurried, nervous pace of those who skirted past him that he was begging. And seeing him standing there, pathetic, in the cold, I thought to myself, crap. How am I going to get into the coffee shop without him shaking me down for money?

I admit it's not impressive, but it's true. I didn't want to be bothered with him. I didn't want to give him any of my money. Who's to say that what he'd spend it on or if giving him a handout was really helping him out? I know Jesus said to give to people whatever they asked from you, but Jesus also said to be as wise as snakes. And I'm no fool. You can't give money to every single person who begs for it. It's not realistic. Jesus never would have made it to the cross if he stopped to help every single person in need. I thought to myself.

Mostly I was irritated. Irritated because on Friday morning I was wearing my clergy collar.

And if Jesus, in his infinite sense of humor, was going to thrust me into a real-life version of this parable, then I was darned if I was going to get cast as the priest. I sat in my car with these thoughts running through my head, and for a few minutes I just watched. I watched as a Starbucks manager saw him begging on the sidewalk and passed by. Then a PetSmart employee saw him begging and passed by. Then some moms in workout clothes pretended not to see him and passed by. When I walked up to him, he smiled and asked if I could spare any cash.

“I don't have any cash on me.” I lied.

I asked him what he needed and he said food. Motioning to the Starbucks behind us I offered to buy him breakfast but he shook his head and explained, no I need food like groceries for my family. And then we stood in the cold and Jameson, his name was Jameson, told me about his wife and three kids and the motel room on Route 1 where they'd been living for three weeks since their eviction, which came two weeks after he lost hours at his job. After he told me his story, I gave him my card and then I walked across the parking lot to shoppers and I bought him a couple of sacks of groceries, things you can keep in a motel room, and then I carried them back to him. It wasn't 14 verbs worth of compassion, but it wasn't shabby.

And James smiled and said, thank you. And then I took his picture. Tacky, I know. But I figured you'd never believe this sermon illustration just fell into my lap like manna from heaven without a picture. So I took his picture on my iPhone. And then having gone and done likewise, I said goodbye. And I held out my hand to shake his.

See?

Isn't that exactly the sort of story you'd expect me to share?

A predictable slice of life story for this worn out parable right before I end the sermon by saying go and do likewise.

And I expect you would go feeling not inspired but guilty.

Guilty knowing that none of us has the time or the energy or the money to spend 14 verbs on every Jameson we meet.

If 14 verbs times every needy person we encounter is how much we must do, then eternal life isn't a gift we inherit at all.

It's instead a more expensive transaction than even the best of us can afford.

Good news? The good news and the bad. There's more to the story. I shook Jameson's hand while in my head I was cursing at Jesus for sticking me in the middle of such a predictable sermon illustration.

And then I turned to go into Starbucks when Jameson said, “You know, when I saw you as a priest, I expected you'd help me.”

And then it hit me.

“Say that again?”

“When I saw who you were,” he said, “The collar. I figured you'd help me.”

And suddenly it was as if he'd smacked me across the face.

We've all heard about the Good Samaritan so many times, the offense of the parable is hidden right there in plain sight.

It's so obvious we never notice it.

Jesus told this story to Jews.

The lawyer who tries to trap Jesus, the 72 disciples who've just returned from the mission field, the crowd that's gathered around to hear about their kingdom work, no matter how big that crowd was, every last listener in Luke chapter 10 is a Jew.

And so when Jesus tells a story about a priest who comes across a man lying naked and maybe dead in a ditch, when Jesus says that the priest passed him on by, none of Jesus' listeners would have batted an eye. When Jesus says, so there's this priest who came across a naked, maybe dead, maybe not even Jewish body on the roadside, and he passed on by the other side, no one in Jesus' audience would have reacted with anything like, “that's outrageous.”

When Jesus says, “there's this priest, and he came across what looked like a naked dead body in the ditch, and he crossed by on the other side,” everyone in Jesus' audience would have been thinking, “what's your point? Of course he passed on by the other side. That's what a priest must do.”

Ditto the Levi.

No one hearing Jesus tell this story would have been offended by their passing on by.

No one would have been outraged.

As soon as they saw the priest enter the story, they would have expected him to keep on walking. The priest had no choice for the greater good. According to the law, to touch the man in the ditch would ritually defile the priest. And under the law, such defilement would require at least a week of purification rituals, during which time the priest would be forbidden from collecting tithes. Which means that for a week or more, the distribution of alms to the poor would stop. And if the priest richly defiled himself and did not perform the purification obligation, if he ignored the law and tried to get away with it and got caught, then according to the law, he could be taken out to the temple court and beaten.

Now, of course, that strikes us as contrary to everything we know of God.

But the point of Jesus's parable passes us by if we forget that none of Jesus' listeners would have felt that way. As soon as they see a priest and a Levite step onto the stage, they would not have expected either to do anything other than what Jesus says they did. So, if Jesus' listeners wouldn't have expected the priest or the Levite to do anything, then what the Samaritan does isn't the point of the parable.

If there's no shock or outrage at what appears to us a lack of compassion, then no matter how many hospitals we name after the story, the act of compassion isn't the lesson of the story.

No matter how many hospitals we name after the story, the act of compassion isn't the lesson of the story.

If no one would have taken offense that the priest did not help someone in need, then helping someone in need is not this teaching's takeaway.

Helping someone in need is not the takeaway.

A little context.

In Jesus' own day, a group of Samaritans had traveled to Jerusalem, which they did not recognize as the holy city of David. And at night, they broke into the temple, which they didn't believe held the presence of Yahweh. And they ransacked it, looted it. And then they littered it with the remains of human corpses, bodies they'd dug up.

So in Jesus' day—

Samaritans weren't just strangers, they weren't just opponents on the other side of the Jewish aisle, they were other.

They were despised.

They were considered deplorable.

Just a chapter before this, an entire village of Samaritans had refused to offer any hospitality to Jesus and the disciples. And the disciples' hostility towards them is such that they begged Jesus to call down an all-consuming holocaust upon the village.

In Jesus' day, there was no such thing as a good Samaritan.

That's why when the parable is finished and Jesus asks his final question, the lawyer can't even stomach to say the word Samaritan. “The one who showed mercy,” is all the lawyer can spit out through clenched teeth. You see, the shock of Jesus' story isn't that the priest and the Levite fail to do anything positive for the man in the ditch.

The shock is that Jesus does anything positive with the Samaritan in the story.

The offense of the story is that Jesus has anything positive to say about someone like a Samaritan. We've gotten it all backwards.

It's not that Jesus uses the Samaritan to teach us how to be neighbors to the man in need.

It's that Jesus uses the man in need to teach us that the Samaritan is our neighbor.

The good news is that this parable, it isn't the stale object lesson about serving the needy that we've made it out to be.

The bad news is that this parable is much worse than most of us ever realized.

Jesus isn't saying that loving our neighbor means caring for someone in need. You don't need Jesus for a lesson so inoffensively vanilla. Jesus is saying that even the most deplorable people, they care for those in need. Therefore, they are our neighbors, upon whom our salvation depends.

I spent last week in California promoting my book, which, if you'd like to pull out your smartphones now and order it on Amazon, I won't stop you. On inauguration day, I was being interviewed about my book. Or at least, I was supposed to be interviewed about my book. But once the interviewers found out I was a pastor outside DC, they just wanted to ask me about people like you all. They wanted to know what you thought, how you felt, here in DC, about Donald Trump. And because this was California, it's not an exaggeration to say that everyone seated there in the audience was somewhere to the left of Noam Chomsky. Seriously, you know you're in LA when I'm the most conservative person in the room.

So I wasn't really sure how I should respond when, after climbing on top of their progressive soapbox, the interviewers asked me, “What do you think, Jason? What do you think we should be most afraid of about Donald Trump and his supporters?”

I thought about how to answer.

I wasn't trying to be profound or offensive.

Turns out I managed to be both.

I said:

“I think with Donald Trump and his supporters, I think, Christians at least, I think we should be afraid of the temptation to self-righteousness. I think we should fear the temptation to see those who have politics other than ours as other.”

Let's just say they didn't exactly line up to buy my book after that answer. Neither was Jesus' audience very enthused about his answer to the lawyer's question.

You know, as bored as we've become with this story, the irony is we haven't even cast ourselves correctly in it.

Jesus isn't inviting us to see ourselves as the bringer of aid to the person in need.

I wish! How flattering is that?

Jesus is inviting us to see ourselves as the man in the ditch and to see a deplorable Samaritan as the potential bearer of our salvation.

Jesus isn't saying that we're saved by loving our neighbors and that loving our neighbors means helping those in need.

No, Jesus is saying with this story what Paul says with his letter, that to be justified before God is to know that the line between good and evil runs not between us and them, but through every human heart, that our propensity to see others as other isn't ideological purity, it's our bondage to sin.

All people, both the religious and the secular, Paul says, all people, both the right and the left, Paul could have said, both Republicans and Democrats, both progressives and conservatives, both black and white and blue, gay or straight, all people, Paul says, are under the power of sin. There is no distinction among people, Paul says, because all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God. No one is righteous, not one, Paul says. Therefore, you have no excuse. In judging others, you condemn yourself, Paul says. You're storing up wrath for yourself, Paul says. No one is righteous, not one. So if you want to be justified instead of judged, if you want to inherit eternal life instead of its eternal opposite, then you better imagine yourself as the desperate one in the ditch and imagine your salvation coming from the most deplorable person your prejudice and your politics can conjure up.

Don't forget, we killed Jesus for telling stories like this one.

And maybe now you can feel why.

Especially now.

Into our partisan tribalism and our talking past points, into our red and blue hues, our social media shaming, into our presumption and our pretense at being prophetic, into all of our self-righteousness and defensiveness, Jesus tells a story where a feminist or an immigrant or a Muslim is forced to imagine their salvation coming to them in someone wearing a cap that reads, Make America Great Again.

Jesus tells a story where a tea party person is near dead in the ditch and his rescue comes from a Black Lives Matter lesbian.

Where the Confederate-clad redneck comes to the rescue of the waxed-mustached hipster. Where the believer is rescued by the unrepentant atheist. A story where we're the helpless, desperate one in the ditch, and our salvation comes to us from the very last type of person we would ever choose.

And when Jesus says, and do likewise, he's not telling us we have to spend 14 verbs on every needy person we encounter. I wish. He's telling us to go and do something much costlier. And countercultural. He's telling us that even the deplorables in our worldview, even those whose hashtags are the opposite of ours, even they help people in need. Therefore, they are our neighbors. Not only our neighbors, they are our threshold to heaven, Jesus.

It's no wonder why we're still so polarized.

After all, we only ever responded to Jesus' parables in one of two ways, wanting nothing to do with him or wanting to do away with him.

Share this post