Matthew 2.13-21

Yesterday we wept in the face of death and we marveled at what God has done to death in Jesus Christ. Not only did Jack Underhill claim that Annandale had “the sexiest pastor’s wife in the United Methodist Church,” Jack wrote a poem nearly every day of his life. Jack loved good food and good wine, and when Jack had imbibed too much of the latter Jack would break out in a dance that was “all elbows.”

Those are the sorts of behind-closed-doors details I have the privilege to overhear when I plan a funeral service with a family.

Usually.

But not always.

Or not always at first.

A couple of years ago, a recent retiree from USAID called the church to inquire after a pastor to conduct a graveside funeral for her husband.

“I attend service every so often,” she told me on the phone, “you’re my preacher even if you don’t know it.”

I did not recognize her name, but when she came to my office to plan her husband’s burial I knew her face. On the Sundays when she attended worship, she always sat in the back of the sanctuary. And every time she came forward to the altar for the Eucharist, her face was so wet she looked like her eyes had been baptized. Receiving Jesus in her hands and on her lips, she would then kneel at the altar rail, slumped over it as though from exhaustion as much as in prayer.

She sat down across from me. I opened my notebook, uncapped my pen, and wrote her husband’s name at the top of a clean page, prepared to note the stories and details and memories she would share.

Instead she pulled a hymnal from a purse overflowing with crumpled tissues, “I liberated this from the sanctuary.”

She opened it up at the page she had bookmarked and handed it over to me. It was page 870: A Service of Death and Resurrection. She had circled parts of the liturgy in pencil— the Word of Grace, the Opening Prayer, Psalm 23, and the Prayer of Commendation.

She had scratched through “Prayer of Commendation” and written beside it with an exclamation point, “Prayer of Condemnation.”

I looked up from the hymnal.

“Those,” she said, “Just do those. It’s best if you don’t say anything about him.”

There were no flowers a few days later at Fairfax Memorial Park. There was no portrait of him. There were only a few mourners. After I had presided over the pieces of the liturgy she had requested, she insisted that she and her sister remain at the graveside until the undertaking was finished.

“I won’t be able to rest until I see him surrounded by dirt.”

It always takes longer than people expect.

As the gravediggers neared the end of their task, she turned to me and shot me the same piercing, quizzical look I’d seen in the sanctuary.

“Do you believe in hell?” she asked me.

“Only when people ask me questions like that,” I started to mutter, but when I looked at her I could tell something more than speculation was at stake.

“I can’t help but wonder why you want to know,” I replied.

“Because I lived with him longer than I should have,” she said, “and if he is in heaven, then I don’t want to go anywhere near it.”

I nodded, the puzzle pieces falling into place.

Her sister put an arm around her, “It’s over now; it’s all in the past.”

The widow looked at me and said, “He first hit me on our honeymoon and he never stopped. His words were such I almost preferred his hands. Pastor, I’ve already been through hell. Heaven would be more of it…”

And she nodded at the bare rectangle in the earth, “…Heaven would be more hell if he is there.”

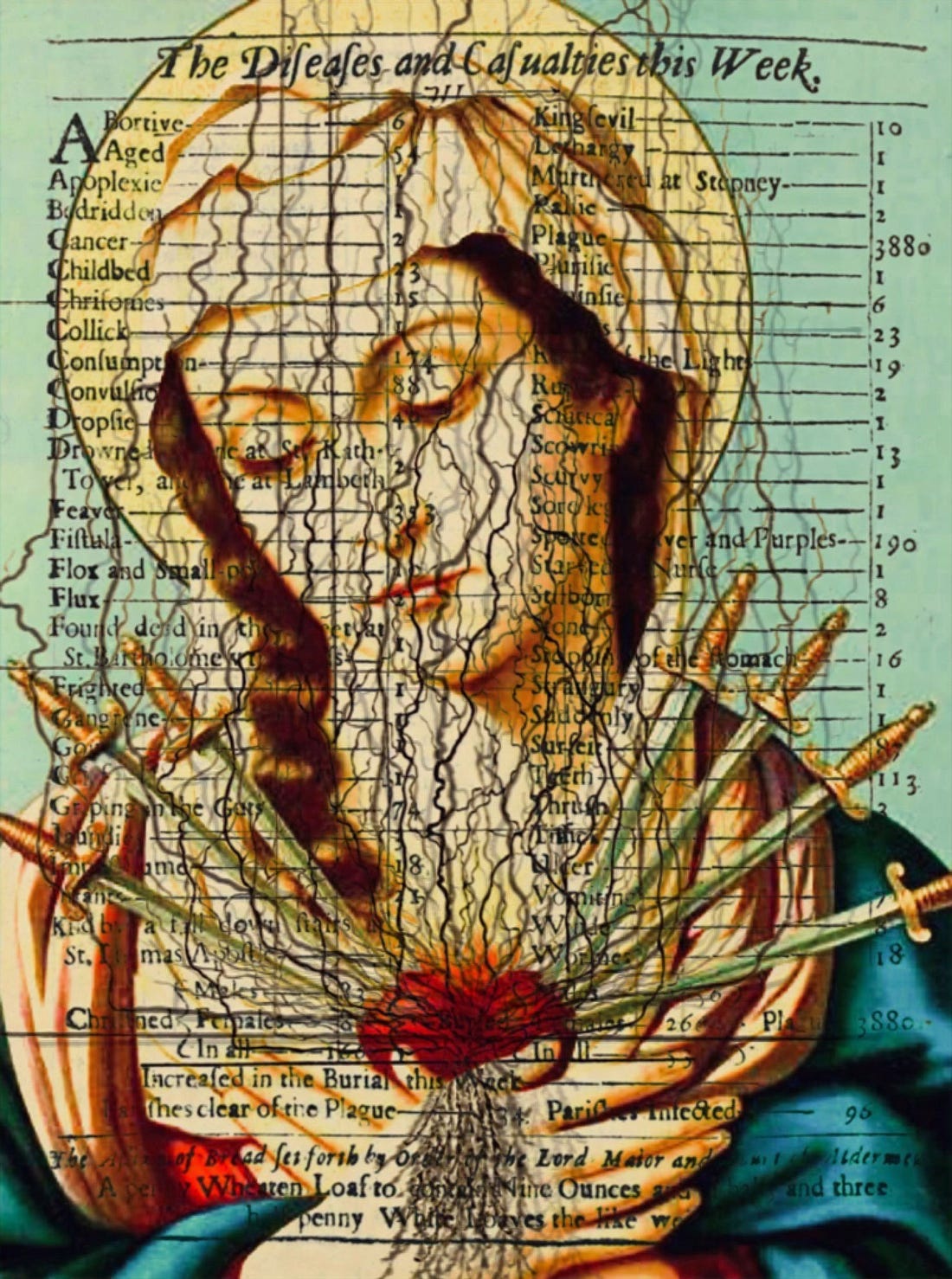

King Herod killed three of his own sons— and his wife— in a mad and jealous drive to protect his throne from usurpers. King Herod’s paranoid rage was so widely known that Caesar Augustus once joked, “It is better to be Herod’s pig than his son.” It is therefore shocking but not surprising that Herod reacts to the magi’s betrayal by dispatching his storm troopers to murder Mary’s boy in the most infallible way possible— the wholesale slaughter of every male in the region of Bethlehem just old enough to be getting their second molars.

The church’s ancient liturgy puts the number of children killed by King Herod at fourteen thousand, a reasonable estimate given that Bethlehem is only nine miles from Jerusalem.

Foreknowing Herod’s plot, the angel of the LORD commands a reverse exodus, ordering the Holy Family to flee— back through the Red Sea— into Egypt. Thus does Mary enact the song she had sung upon the annunciation. She who was rich and filled with good things— very God from very God— is brought low in spirit and sent empty away into Pharaoh’s land.

Being a congenital contrarian, I preached on this passage for Christmas Eve a few years ago. Maybe you remember it. Perhaps you’re still recovering from it. After the seven o’clock service, when the candles had all been blow out and the lights turned back up, one of you approached me at the altar. I could tell from her countenance that, without intending it, I had ruined her Christmas.

She wasn’t angry, exactly.

She was troubled.

“If Jesus dies for his enemies,” she broached, “if Jesus is willing to die for the ungodly like you’re always preaching, then surely Jesus would rather not be born if his birth meant the murder of all those children. Not to mention the trauma to all those mothers and fathers. If those details matter only to me…if they don’t matter to God, then…”

She trailed off, hesitant to voice the obvious conclusion.

I offered her an apparently inadequate response because when I got home half-past midnight after the final Christmas Eve service, she had sent me an email. It was blank save the sentence in the subject line, “Why would Mary say “Yes” to being God’s heaven if it meant hell for so many others?”

And she was right to push back and question, question God.

After all, what does Mary carry in her womb if not the criterion by which we can judge all things, including his Father?

In an essay for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, my former teacher David Bentley Hart attempts to put skin on the subject matter by beginning with a story.

He writes:

“My friends’ son recently had been diagnosed as having Asperger’s syndrome. As tends to be the case with many children classified as “on the spectrum,” he was often intensely sensitive to, and largely defenseless against, extreme experiences, including moral dissonances.

So it should have surprised no one when he fell into an extended period of panic and depression, after a guest preacher visiting his parish happened to mention the eternity of hell in a sermon. The boy's reaction was one of despair.

All at once, the boy found himself imprisoned in a universe of absolute horror, and nothing could calm him until his father succeeded in convincing him that the priest had been repeating lies whose only purpose was to terrorize people into obedience.

This helped him regain his composure, but not his willingness to attend church; if his parents so much as suggested the possibility, he would slip into a narrow space behind the balustrade of the staircase where they could not reach him..”

Having told the story of his friend’s boy, David Bentley Hart then characterizes the notion that God will contentedly allow a remainder of his creatures to suffer eternal torment— he calls such a notion “spiritual squalor.” And then he adds, “Another description for a “spectrum” child’s “exaggerated” emotional sensitivity might simply be called “acute moral intelligence.”

Here is my question.

If we accept his premise that the torment of even a single one of the LORD’s creatures in eternity is “spiritual squalor” and unworthy of the Goodness of God— if we accept that premise, and I do— then what do we say about torments not in eternity but in time?

If the sorrows and the sufferings of the past simply perdure without rectification, do they not stand as a demonic testament to God’s failure to finish the good work he began in you? If past traumas and historical tragedies stand forever opposed to God, then is not God’s goodness eternally compromised by a deficient almightiness?

As the church father Maximus the Confessor puts it, “Nothing has yet happened just because it has passed.”

Nothing has yet happened just because it has “happened.”

In other words—

Many items of history are thus far not true events.

That which has happened is still unfinished.

Much of what is in the “past” is not yet God’s creation.

Yes, the claim contorts and confuses our sense of time; nonetheless, it is the clear and straightforward assertion of the scriptures. To corroborate the claim, you need look no further than Mary the Mother of God.

Seldom do we pause Christmas pageants to ponder the peculiar detail, but in the Gospel of Luke, the angel Gabriel addresses Mary, “Hail, full of grace, the LORD is with you.” The angel acknowledges her status again two verses later. Biblically speaking, grace is neither a generic term nor a nebulous energy. All grace flows from Christ’s obedience unto death— “even death on a cross.”

Chew on the mystery.

At the Annunciation, the angel addresses Mary as a recipient of the very grace won by the merits of her son on the cross. Again, grace is reckoned to human creatures only on account of Christ’s work on the cross—a temporal event. The grace which fills Mary is a grace that requires Christ’s own faithful life, passion, death, resurrection, and ascension. Yet somehow Mary is a recipient of events which will transpire in the future.

Mary’s status (“full of grace”) is an effect of a cause that would not occur for another thirty to thirty-three years. And yet it was this very effect, this entirely salvific grace, which created a necessary condition for Mary to consent to Christ’s own conception in her by the Holy Spirit. Mary’s “Let it be with me according to your word” was itself made possible by her Son’s consent to the cross in the Garden of Gethsemane.

We think of time as events in a fixed, unalterable sequence. This is not how the scriptures conceive of time. As Jordan Daniel Wood writes, “The incarnation of the Son is an event whose intelligibility requires us to think beyond the serial logic of time.”

Mary is but one example of how the scriptures trespass our sequential logic.

It is all over scripture.

It’s what the Gospel of Matthew shows you when he reports that at the crucifixion when Jesus cried his last and surrendered his spirit, the bodies of Old Testament saints were raised from the dead. It’s what the Book of Hebrews tells you when it proclaims that Christ’s sacrifice is effective backwards through time. It’s what Ephesians proclaims straight out of the gate: Christ Jesus chose us— when— before the foundation of the world. It’s what we pray every time we pray the prayer Jesus so commanded, “…on earth as it is in heaven.”

Make time and eternity rhyme.

If we did not believe God happens to time in such an odd manner, then, as Paul insists, we would still be in our sins. After all, what is faith but trust that a past temporal event somehow redounds down the timeline into the future in order to benefit you?

As Christmas Eve turned to Christmas Day, I wrapped my wife’s presents while I watched Bad Santa. When I was done, I threw back the last of my drink and I picked up my phone and I typed a quick reply to her question, “Why would Mary say “Yes” to being God’s heaven if it meant hell for so many others?”

“Because,” I wrote, “Not only did the LORD choose his Mother out of all the available contenders across time, unlike all other soon-to-be parents his Mother knew the child she would give to the world and, therefore, she knew that he will in the fullness of time transfigure every hell into heaven. This is why Christians have so often spoken of heaven as the Fulfillment with a capital F.”

Mary is the rule not the exception. She is the harbinger of your destiny. The coincidence of opposites in her (a finite creature containing the infinite God) scripture says that is your future too. And not simply our destiny, it is God’s providential desire for every part of creation. Again it is the clear and straightforward claim of the scriptures.

God set Jesus as a plan for the wholeness of time, to unite all things in Christ.”

That’s Ephesians 1.10.

“In Christ all things hold together…” Paul writes to the Colossians, “And Christ is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead; so that, he might pervade all things. For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him to reconcile to himself all things.”

Not all people!

All things.

“The kingdom of God is not coming in ways that can be observed,” Jesus says to the Pharisees.

Why cannot it not be observed?

Because it will pervade all things.

“The Kingdom of God will be inside of you,” Jesus tells them.

Paul echoes Christ’s teaching, writing to the Corinthians that when the incarnation is complete “Christ will be all in all things.”

Jesus will be all in all things. That is, all things will be made like Mary. All finite creatures will contain the infinite God.

And do not forget: one of those things is time.

God creates not simply light but the first day. He makes man and woman but also minutes and moments. Every single instance of your life is as much God’s creation as a tree or a bird, a quark or an atom or my words to you right now.

History is every bit the creature made by God as a hippopotamus.

Thus every moment in time has a divinely-willed end. Every moment of history has a goal which God desires. This demands you remember a basic tenet of the faith: God wills only goodness and love; God wills neither sin nor suffering.

Trust me, I know what it’s like to wonder, “Why are you doing this to me God?!” Despite my faith, I utter it about four times a day, every time I swallow my chemotherapy. I know what it’s like to wonder, “Why are you doing this to me God?!” But guess what— this is why you need a preacher—because he’s not!

He’s not.

God wills only goodness and love.

God wills neither suffering nor sin. Evils are not creation. Sin is not a thing but an absence. Tragedies are not real expressions of God’s will. Traumas are not true events; they are disfigurements to God’s time. And so long as they abide, history is not yet creation— that’s St. Gregory of Nyssa.

Once again:

Time is a creature of the God who wills only goodness and love.

Time is one of the “things” in which Christ will be all.

Time for all us presently contains more moments of pain and suffering than we dare to share.

Just so, the promise.

That part of time we call the past is itself a part of the creation groaning in labor pains, waiting for it to be made whole. This is precisely what the LORD announces from heaven’s throne to the prophet John, “Mourning and crying and pain will be no more.”

How?

Because the minutes and moments that produced mourning and crying and pain will be transfigured. “Those former things,” the LORD says to John, “will pass away.” That past will pass away. It will be undone. It will be transfigured. And only then will creation be creation.

Nothing has yet happened just because it has passed.

Paraphrasing the church fathers, Jordan Daniel Wood writes, “God will transfigure the wills of every participant in every event at every moment of time in order to make these real events, to make them what God has beneficently and lovingly willed for them to be from eternity.” Or as Maximus the Confessor puts it, “For the Word of God and God wills eternally to accomplish the mystery of his incarnation in all things [including time].”

If Mary contains in her belly the criterion by which we can judge the goodness of all things, including God, then anything short of the promise of time’s transfiguration is not a gospel worthy of her son.

I had nearly made it back to my truck where it was parked on the path that snakes its way through the cemetery. She had a hand on the handle of the passenger door of a blue Toyota Camry when she said with great volume and not a little irritation, “You never answered my question, Pastor. I can’t stand the thought of heaven if it means he’s there.”

I nodded. She stood by the car. Her face told me her gas would go bad before she’d leave without a response.

So I said, “The promise of the gospel is that when you enter into heaven, the man you will meet there will be different than the man you knew. For that matter, you will discover the two of you had a marriage made altogether different than the version of it you just buried. Your wounds and your memories won’t be healed; your whole timeline will be transfigured according to God’s will for it.”

She shot me that same piercing, quizzical look I’d seen in the sanctuary.

I added, “It isn’t just that you had hopes for your life and marriage. God does too. And I can’t explain it exactly but somehow God’s going to get what you both want.”

“Why didn’t you say anything like before now?”

“You would only let me do the parts you’d circled, remember.”

“Are you a smart-ass to everyone?”

“No,” I lied.

But if that lie constitutes a sin, then one day, somehow, I didn’t.

What Maximus the Confessor calls “the cosmic mystery of Christ” is the promise that God is at work in Jesus Christ to heal your whole timeline, to mend everything that is broken, every wrong you’ve wreaked, every trauma you’ve suffered, all the tragedies you’ve doom-scrolled— without undoing you, all of it will be undone.

Transfigured according to the LORD’S love and goodness.

Christ will be all in all things, every minute and moment.

Such that somehow in Bethlehem beside the magi gifting their frankincense, gold, and myrrh will be Herod, on bended knee and joyfully offering the child his crown.

Time will be transfigured.

I know it sounds impossible.

I know it lands as incomprehensible.

Then again, on Holy Thursday Jesus institutes the Eucharist. He distributes the bread and the wine, bidding his disciples to consume them as his own broken body and shed blood.

There and then they are that!

Even though he will not suffer until Friday afternoon.

Even though he will not be raised until the third day.

Even though he will not ascend to the Father until fifty days thereafter.

All of which, Paul writes, are the necessary preconditions for Jesus’ presence in loaf and cup on Thursday night.

Listen, I tell you a great mystery!

All events, A-Y, precede the final Event, Z, when Christ will be all in all things. And yet, Z is the very ground and destiny of every event that came before it.

In case that’s not clear to you, come to the table.

That the loaf and the cup are his body and blood is but a reminder that time doesn’t work the way you think, and therefore not only your future but your past and your present are all far better than you ever dared to imagine.

Share this post