Genesis 28

Five years ago, three years after he should have been no longer alive, the esteemed New Testament scholar, Richard Hays, addressed those who had gathered to celebrate his retirement from Duke Divinity School.

At the top of his lecture, Hays said,

“I’m grateful to all of you who’ve come here this evening to hear a few reflections from me on the occasion of my retirement. I’m grateful for all your prayers over these past three years.”

They worked.

God answered them.

“I’m grateful for all your prayers. Most of all, I’m grateful to God for granting me a little more world and a little more time to think back on what has been and to ponder what is to come. The key note of all I have to say is gratitude. This is the day that the Lord has made. Let us rejoice and be glad in it.”

This is the day the Lord has made. That’s not a sentiment. It’s a claim.

“Most of you know…three years ago I received a devastating diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, and I went on medical leave to undergo chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. When I left the dean’s office that July, I left in tears with my hair falling out. I took up the tasks of reviewing my will and writing directions for my funeral service. As I stand here tonight, I’m unexpectedly able to look back on that night, that year, of now done darkness. Chastened, hopeful, healed. I’m grateful for your prayers.”

A couple of year ago, I was in my truck, driving to the office, when a different Duke professor called me.

Over the years the theologian Stanley Hauerwas has become more than a mentor.

He’d been ill and had undergone surgery in England, and I’d left him a message inquiring about his health and spirit.

That morning on the way to church, he called me back and before I could even say hello, his gravely Texas accent barked out, “Jason I can’t piss, and it’s just so damn painful.”

As I pulled into the church’s parking lot, he described all the complications he’d suffered following what should have been a routine procedure.

I listened.

But I knew that Stanley is not the sort of Christian to be satisfied with a preacher who offers nothing but active listening.

So I said to him, “I’ll pray for you, Stanley.”

“You damn well better do it now,” he grumbled, “I’m miserable, in agony.”

I cleared my throat and was about to begin praying when Stanley interrupted me.

“And Jason?”

“Yes, Stanley?”

“If you’re not going to pray for God to heal me, then, hell, just hang up the phone right now already.”

I laughed and I prayed to God for just that and when I was done he said, “Thank you. I’m grateful for your prayers.”

After having dishonored and deceived his father and stolen his elder brother’s blessing, Jacob nevertheless receives a prayer from his father.

“May God Almighty bless you…” Isaac prays, “May God give the blessing of Abraham to you…”

With this prayer in his pocket and a staff in his hand, Jacob sets out for a life in exile on his uncle Laban’s estate. But no sooner has Jacob left his father’s home than God Almighty answers Isaac’s prayer. Jacob makes camp at Bethel, the very place where his grandfather had built an altar and called upon the name of the Lord.

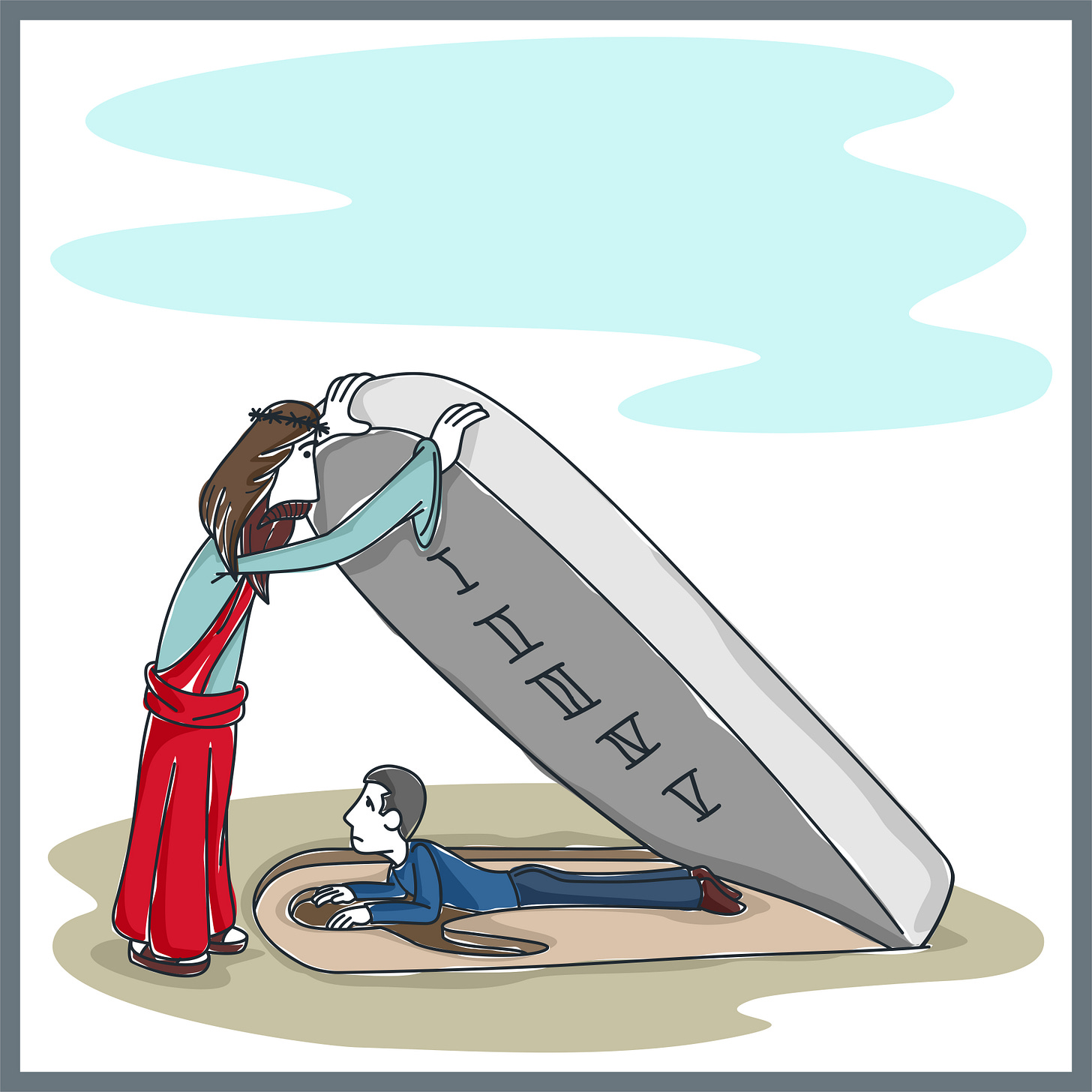

Jacob picks out a stone for his pillow. He lays down to sleep. And he falls in to a dream. Jacob dreams of an earthbound exit off a heavenly highway jammed with angelic traffic. And then, after the dream, God Almighty answers Isaac’s prayer.

God appears to Jacob— for the first time to Jacob— and God says,

“I am the Lord, the God of Abraham your father and the God of Isaac…Know that I am with you and will keep you wherever you go, and will bring you back to this land; for I will not leave you until I have done what I have promised you.”

Notice—

In answering Isaac’s prayer, God says nothing to Jacob about Jacob’s sin, neither his trespass against his brother Esau nor his transgression against his father. It’s all just blessing and grace.

Jacob is addressed by God. Jacob is addressed graciously by God. And God addresses Jacob as a result of Isaac’s prayer for Jacob. No doubt Jacob is grateful for Isaac’s prayer.

Jacob meanwhile responds to the Lord’s address of him by himself praying. Jacob’s prayer at the end of Genesis 28 is a clear indication that we should not expect a person’s religious experience to change their character in any significant manner. The Jacob who prays after having had this mystical encounter with God is the same Jacob who conned a birthright from his brother and stole a blessing from his father. Jacob prays,

“Since you’re going to be with me, Lord, abiding with me and all, how about you take care of the groceries too? And I had to leave home in a hurry. I only packed a spare change of clothes. How about you take care of my wardrobe as well, God? And bring me back to my father’s house in one piece why don’t you? Keep Esau from killing me. If you’ll do all that, Lord, then, yeah, you can be my God.”

Jacob prays without tact, humility, or self-awareness.

And God does just as Jacob asks.

Jacob is clothed and fed and sheltered and reconciled.

Nothing that happens in the world happens apart from the free willing of God.

Yet…God is persuadable.

Several years ago now, I was at the infusion center to receive the Neulasta injection that bookended my every round of chemo. An old woman sat directly across from me, a red-orange tube running from a bag to her chest. She wore a blue scarf with peacocks on it around her small, bony head. Her face looked so sunken and her skin so stretched and translucent that guessing her age felt impossible. She greeted me—exhausted, her eyes only half open—with a distinct prairie accent when I sat down and cracked open my book.

I didn’t get past the first page.

She started to cry—whimper really—from the sores her chemo-poison had burnt into her mouth and tongue and throat. Beseeching the nurse, she pleaded, “make the pain go away.” She kept on like that, inconsolable, with no concern for what I or anyone else might think about her. In a different-size person you’d call it a tantrum.

Seeing her there, spent and defeated, I felt compelled to do the only work I could for her. I prayed. Quietly, under my breath, just above a whisper, my lips moving to the petitions. And when I finished, I made the sign of the cross over her.

“You religious?” the man in the next infusion chair asked me.

“Sort of, I guess.”

He went to wave me off, dismissively, but then remembered his arm was taped and tethered to tubes and the tubes to an IV pole. He’d been on the phone on work calls almost the whole time I’d been there. A gray tie that matched his hair hung loose from his unbuttoned collar.

“You really think that stuff works— prayer?”

He said it in a tone that suggested no believer anywhere at anytime had ever wrestled with such a question.

“Well,” I replied, “If prayer doesn’t work, then it’s entirely a waste of time.”

If prayer doesn’t work, then it’s entirely a waste of time.

He nodded seeming to appreciate that I had not evaded the stakes at the heart of his question.

“I’ve got a partner,” he said, “in my firm. He prays. He says he does it because it changes him. Like, he prays for patience and the practice of praying makes him more patient. Like meditation I suppose.”

I nodded and smiled wryly.

“You’d never know it from the way a lot of Christians talk about prayer,” I said to him, “But the content of prayer is not irrelevant to its benefit.”

The content of prayer is not irrelevant to its benefit.

He didn’t follow me so I said, “You’d be surprised how many people pray who do not believe in prayer.”

“A lot of them are ordained,” I added.

He laughed, and then he went back to his work.

A couple of minutes later he sat his phone down on his lap and raised his hands in a “What gives?” gesture.

“But how?” he said, “I mean, come on! You’re telling me that you think we can change God’s mind about God’s will?”

I smiled a wide and crazy smile.

“It’s totally crazy, isn’t it?” I said, “It’s tremendously preposterous— to say nothing of presumptuous— but that’s the claim. That’s the claim Jews and Christians make (at least the ones who haven’t lost their theological nerve). If the claim is wrong, then the gospel is a lie and prayer is nothing but a bunch of hot air.”

And then I pointed at the exhausted, whimpering woman across from me.

“The claim is not only that we can tell the Father what he ought to do about her; the claim is the Father will listen and may heed us.”

The old rabbis considered Jacob the father of faith.

How?

Jacob doesn’t know the promise of God so as to trust it. Jacob has not heretofore had any experience of God. If faith denotes a spiritual experience, Jacob has not yet had one. How is Jacob the father of faith? Jacob doesn’t even know the stories of the faith— he doesn’t realize he’s pitched a tent in the very spot Abraham called upon the Lord. How is he the father of faith? If faith is equivalent to virtue (like many of you imagine), Jacob has none.

Jacob is the father of faith, the old rabbis attested, because Jacob made a verbal reply to the God who addressed him.

He prayed.

He prayed a petitionary prayer.

He prayed, “Father, give me this, that, and the other, and you can be my God.”

The law commands faith.

The creeds describe faith.

Prayer is the act of faith.

Prayer is the act of faith, and, put the other way around, a sure sign of a lack of faith is a reluctance to pray boldly.

Jacob is the father of faith because prayer is the most elementary act of obedience. It does not matter how many good works you do or how much you give. Alms to the poor do not substitute for prayer. Jacob is the father of faith because prayer is the most elementary act of obedience, and prayer is the most elementary act of obedience precisely because it is a correlative of the gospel.

The gospel is an address to you for you from the Living God. “This is my body given for you,” he says to you every Sunday. “In the name of my Son, your sins are forgiven.”“This is the word of God for the people of God.” Since God initiates a relationship of address, it follows that, in return, he wants to hear from you.

Prayer is the most elementary act of disobedience.

Elementary but offensive.

Just imagine—

Imagine an anthropologist from outer space, observing for the first time, Jews and Christians engaged in prayer.

What would she think?

Surely, she would conclude that we were engaged in dialogue with one on whom we are utterly dependent but one we could nevertheless influence.

It’s quite obvious.

Yet if asked a question like, “Do you really believe your prayer can change God’s mind?” many believers balk at the unambiguous implications of our practice.

Our evasions are not dictated to us by scripture.

The God of the Bible hears the cries of his people as slaves in Egypt and is moved to deliver them. The God of Israel is talked off the ledge by Abraham, who convinces the Lord not to destroy every citizen of Sodom. The God of Abraham is persuaded by Jacob to go beyond the promise and also provide for Jacob’s room and board and meal plan.

The God of the Bible is persuadable.

Prayer is elementary but it’s offensive.

Think about it—

When we bring God our petitions, we presume to advise the Maker of All that Is about how best to order the universe. That’s what we’re doing; that’s what we presume. We don’t pray simply because such prayers form us. We don’t pray to accrue any merit. We’re not practicing mindfulness.

No, we pray to tell the Creator how to govern his creation.

We presume that the cosmic course of history can be brought to respond to our concerns.

Such presumptions are presumptuous.

Now to get overly philosophical or polemical but all of you have been shaped deeply by the Enlightenment’s conviction that we inhabit a mechanical universe whose processes (called nature and history) are immune to petition.

The great temptation, one which traditions like Methodism have largely fallen prey, is to reconstruct a God appropriate to this supposedly indifferent, mechanical universe.

Thus:

A God too impersonal and static, impassible and distant, to be pleased by our praise or persuaded by our petitions.

But if the gospel is true, if scripture is reliable, if faith is possible, then all of this is backwards.

This is the day the Lord is making.

If bold, presumptuous petitions are implausible in our world, then it is the world we misunderstand not God.

Which means, we’re worshipping an idol and we ought to repent and turn to the true God.

The Persuadable God.

In his recent book, Peace in the Last Third of Life: A Handbook of Hope for Boomers, Paul Zahl writes,

“I got a sincere but somewhat pathetic prayer request from an old friend last year, asking me to pray for her friend’s stage- four breast cancer. My friend asked me to pray for good medical care for the person, for patience and endurance for the person’s husband, for a sound mind among her family that would know when it was time to “pull the plug,” and for a loving exchange of ideas concerning the inevitable funeral. I wrote back, asking if the possibility of praying for remission in this case were on the table. She wrote back saying that it had not come up.

Then later, during the coronavirus pandemic, I received a series of prayers from the chaplains of the Episcopal prep school I attended. Not one of the prayers included a single note of supplication for the virus itself to be restrained or for healing to be given to any who had contracted it.

I used to be diffident about praying for the remission or healing of a physical illness, let alone of a mental incapacity or disturbance. I would pray for the sufferer’s acceptance and serenity much more often than for God’s intervention and victory.

I was wrong.”

Paul Zahl may have been wrong, but he is hardly alone.

When I first got cancer several years ago, I was astonished at the apparent unbelief in prayer by those who do it. Every person was sincere. It just goes to show how little sincerity has to do with discipleship.

“l’ll pray that God gives you strength,” people would tell me.

“I’m praying that God will give your doctors wisdom,” pastors told me.

“You’re in my thoughts,” far too many Christians told me.

Your thoughts? What in the hell good are your thoughts going to do? I’m dying. Why don’t you pray for God to make it not so?! Why don’t you attempt to persuade God to heal me?

Some did so pray.

And I am grateful for their prayers.

At the beginning of the Gospel of John when Jesus calls Phillip and Nathanel, Jesus reveals to them that he is the ramp Jacob sees laid down from heaven onto the earth. The Son of God, Jesus says, is Jacob’s ladder; that is— pay attention now, the Son is the means by which our communication with the Father is possible. This is Jesus’s point when he gives us permission to pray to his Father as our Father.

As Robert Jenson says, “This is to be taken seriously.”

We can dare address God with our petitions because Jesus has invited us into his conversation with the Father.

God is so gracious.

He hasn’t just made a decision about you in Jesus Christ. On account of Jesus Christ, he’s willing to listen to you. He doesn’t just allow he invite our views to be heard and weighed in his care of the universe, exactly as a parent listens to and considers seriously the views of their children.

“Our expressed opinion,” says Robert Jenson, “is an essential pole of the process of God’s decision-making.”

Because of Jesus, because you’ve been incorporated in to him, because you’ve been invited in, because his Father is now your Father too, the life of the Trinity is now like a parliament in which you are a member.

The life of the Trinity is now like a parliament in which you are a member.

God wants you to speak up. Make a motion. Voice your opinion.

The claim implicit in Christian prayer is astonishing. Most will not believe it.

Quite simply:

To pray to stake a claim over the care of creation.

To pray is to presume co-determination of the universe.

To pray is to participate in Providence.

Any lesser claim evades the clear implications of scripture and makes prayer nothing but an empty practice of piety.

There is perhaps no stronger indictment of the Church in a secular age than the fact that this needs to be said clearly and without hesitation:

Prayer accomplishes things.

When we pray for someone, when we petition God on their behalf, we intend thereby to accomplish something for them.

Prayer is the work grace gives us to do. It is our work in the world on the world. It is our work in the world for the world’s future.

Prayer pulls us into the working out of God’s governance of the world. Prayer is our participation in Providence. In Jesus, the Father has given you a say in how his history will come out.

So, let us pray.

Let us pray prayers that are big enough and bold enough that only God can bring them off.

Pray for the war in Ukraine to be ended. Pray for all its victims to be mended. Pray for the Lord to smite Vladimir Putin. Pray for a major health event to strike Donald Trump. Or Joe Biden if that’s your politics.

In either case, pray like prayer does work.

Pray for every racist cop to be unemployed. Pray for every homeless to be housed— not fed. Pray for me to be a better preacher. Pray for Peter to be a better dresser. Pray for the gospel to reach your unbelieving child. And gift them saving faith. Pray for miracles. Pray for your addicted loved one to be, inexplicably, set free. Pray for all professional Philadelphia sports teams to fail.

Pray for Gary to be healed.

Pray for Gary and Mike and Clarence and Denny and anyone else not yet on the other side of the “now done darkness” to be healed.

Prayer accomplishes things.

You can change the Persuadable God’s mind.

By the baptism of his suffering, death, and resurrection, Jesus Christ has invited you into the household called Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Don’t tiptoe around quietly.

Don’t put your head down and your hands in your pockets.

Don’t keep your opinions to yourself.

Speak up!

SPEAK UP!

If the world knew what you know by faith, they would be grateful for your prayers.