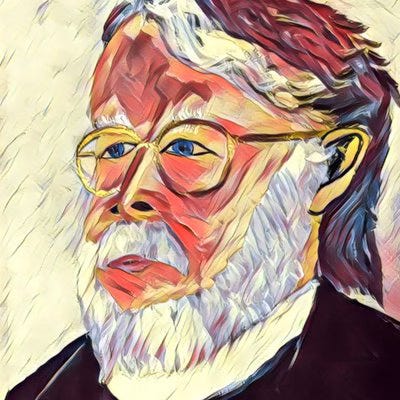

One of my regrets in life is that I did not seize the moment and forge a deeper relationship with the theologian Robert W. Jenson. Jens was in residence at the Center for Theological Inquiry when I was a student at Princeton Theological Seminary. I had started to read him in college at the suggestion of Eugene Rogers and David Bentley Hart, two of my first teachers. They had promised me that he was the best guide to ascend the mountain that is Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics. In the beginning, I understood Jens’s work well enough to be intimidated by his brilliance and concision. As a graduate student, I worked in the mailroom at Princeton and hand-delivered Jens’s mail every day to him at CTI. Despite such proximity, I only dared strike up a few conversations with him over the years.

One of my gratitudes is that Chris E.W. Green prodded me to go back and reread all of Jens’s work. As a more seasoned gospeler, as Jens would say, I have benefited anew from his attempts to say what we must say in order to say that Jesus lives with death behind him.

Another gratitude is that the podcast I share with friends was the last venue for an interview with Robert Jenson before he died in 2017. My friends Chris Green and Ken Tanner did the interview. Due to the nature of his Parkinson’s, Jens struggled with his speech and the audio requires patience on the part of the listener.

Thanks to Ken’s and Chris’s work we have been able to produce an accurate transcription of this last interview with Robert W. Jenson.

Spoiler:

He’s a universalist.

soli Deo gloria

Lift up your hearts unto the Lord. Heavenly Father, be with us in the coming days of trial. We thank you for whatever you have contributed to those days, to the work of Robert Jenson. He does not deserve the credit; you do. But we wish to thank you for it all the same. Amen.

Kenneth Tanner: Thinking back on your book, Conversations with Poppi about God—all those wonderful conversations you had with your then eight-year-old granddaughter, Solveig, where you talked at her level, trying to listen carefully to what she was asking, and responding with your characteristic humor—I asked a number of Holy Redeemer families if their children had questions they would like to ask you. And June, we call her Junebug, an elementary school student here in Michigan, sent me this question: “How is it that Jesus can see us but we can’t see him?”

Robert Jenson: Well, we can see Jesus. If we ask what the risen Christ looks like, the answer is, He looks exactly like that loaf of bread on the table and the cup of wine that goes with it. A living person looks like whatever he or she does at a particular juncture in his life. What does a human of two weeks gestation look like? Exactly like that fetus; that is that human being to be seen. By extension or analogy, we can ask what the risen Christ looks like and answer, He looks like that loaf of bread. The doctrine of transubstantiation in the Roman Catholic Church is devised to explicate that phenomenon. I don’t think it needs any explanation. But if you need one, you can try transubstantiation.

Chris Green: My son Clive, when he was three or four, asked his mom this question, which I’ll put to you now: When I get to heaven, do I tell Jesus or you when I have to go to the bathroom? I’d love to hear you talk a little bit about what we can expect of resurrection embodiment in the end—not only for Jesus, but also for ourselves.

Robert Jenson: At the very end, when the Lord comes in his glory, we will discover that the New Testament was very cautious about what it said. As to what damnation looks like, it’s very clear. But when it comes to the positive side of the final revelation, it turns to poetry. I have occasionally attempted to sum up that poetry by saying the final transformation of creation is into one vast implosion of love. What’s an implosion of love? In one way I don’t have the slightest idea… Nevertheless, it communicates. So the sum-up I have played with is “a vast implosion of love.” I have another sum-up that I play with and that’s to say, at the end of it all, the rest is music. A vast hymn, a three-part fugue played by God, with God, and involving us as variations on the theme. Does that help any at all?

Chris Green: Somewhere you talk about the bodily or sensual enjoyments we might enjoy. You ask if what the vintner practiced in this life won’t matter then. Maybe say something about that, the continuity between this life and the life to come.

Robert Jenson: You know, that question of the continuity is one of the vexed questions of all Christian theological history. I’m not sure that it’s solvable, short of being there in the end. We will be identifiable to each other, but how—I figure we’ll have to wait and find out. Dante, at the end of the vision of heaven, sees Beatrice—his beloved, whom he has sought through his life—as one of the members of the heavenly choir engaged in adoration of God. She leaves her place in the choir and comes to tell Dante what he’s seeing and hearing, and then she goes back. Is that the end of the love affair of Beatrice and Dante? It’s not altogether clear. In Dante, it looks a little bit too much that way for my taste.

Chris Green: Let’s talk about universalism for a moment. How has your mind changed on that over the years? Is everyone in the end included, brought into that vast implosion of love, or not? If so, how?

Robert Jenson: All the pressure of my theology, and I dare say of one stream of church theology (like in Gregory of Nyssa), presses toward universalism. Do I go over the boundary and say all will be saved? Karl Barth cautions against doing that, because of course there are passages in the New Testament that strongly suggest not. Sometimes, in a lightheaded mood, I have said, Well, sure, there’s hell; it’s just that there won’t be anybody in it. I guess I am a universalist. A great many other people in the present theological time are pressured the same way. Is that just a matter of fashion? Because theology does have fashions. I don’t know. I hope not. And maybe what we have is universal hope rather than universal knowledge.

Kenneth Tanner: One of my friends likes to say that there is a hell, but you have to fight your way through the love of God to get there.

Robert Jenson: Can you do that? Is the love of God ever finally defeated? I don’t think so. But that may just be because I live in the 21st century.

Chris Green: In one of our first conversations, I asked you a similar question and I told you that I was afraid of my own conviction. You said you were afraid too, for the reason you just described, afraid of being caught up in the spirit of the age and not the gospel.

Kenneth Tanner: I think you said, Chris, that if Jens were a universalist, he was one in fear and trembling.

Robert Jenson: Well, that’s me. And I guess I always have been. I don’t think my mind has ever changed. As soon as the question appeared in my consciousness, I went the one way.

Kenneth Tanner: Another question, this from a young woman named Catina: Why do some people not experience healing? Some people do and some people don’t.

Robert Jenson: Because that’s the will of the Lord. You know that I have Parkinson’s disease, a degenerative disease. It isn’t reversible. Nevertheless, I pray to be healed. And one has to live with that. As to why there is so much suffering in the world, so much evil, that’s the famous theodicy question. And in my judgment, it’s the only good reason not to believe in God. If we nevertheless say, despite all the suffering in the world, God is good, that’s as far as we can go. There is no present available answer to the theodicy question, despite the fact that Leibniz thought there was.

Kenneth Tanner: Is part of the answer that God in Jesus Christ is with us and our suffering? He’s not standing outside of the human condition.

Robert Jenson: Oh yes, but why was it necessary for that to be the case? You just push the problem back one step. Look, the various answers proposed to the theodicy question may be of help in various contexts, but, to be slightly superficial, they don’t finally get God off the hook.

Kenneth Tanner: Reading your theology is not an exercise in scholarship; it’s an exercise in piety (to use a big word that people don’t use much anymore). As I’m reading, I’m involved in prayer. I wonder if you could answer that question, What is prayer?

Robert Jenson: Talking with God. Speaking up in the divine conversation. The Father and the Son in the Spirit are carrying on a great conversation, and as members of the body of Christ we are empowered and demanded to speak up in it. Our voices are very little, but they don’t count for nothing.

Kenneth Tanner: This gets to the question of change in God. Do we, by our prayers, affect change, the outcome of events?

Robert Jenson: Yes. I know that’s a drastic answer. But otherwise there’s no point in praying. At least not petitionary prayer. And the main part of Christian prayer is petitionary. The Lord’s Prayer is a series of petitions, so we can’t get off the hook by saying there are other kinds of prayer than petition. As Luther said shortly before he died, Wir sind bettler; hoc est verum. “We are beggars. That’s the truth.” And our begging is answered. Otherwise, why do it? I’m afraid that’s all I have to say on the question.

Chris Green: In your conversations with Solveig, she asks you about God’s motives. I’d love to hear you pick that up again all these years later. What motivates God—in creating at all, in saving us?

Robert Jenson: Since God is a communion, it is sort of natural to God—sort of natural—to desire to expand that communion. Solveig asked me the question, “Why isn’t he satisfied with Adam and Eve?” The answer I gave is, “Because he wanted to include Solveig.” I think that’s a pretty good answer still.

Kenneth Tanner: Yes, you say, “One way of saying what happened with Jesus is that Jesus so attached himself to you that if God the Father wants his son, Jesus, he has stuck with you too.”

Robert Jenson: That’s flippant, but correct. By the way, that’s Jonathan Edwards.

Kenneth Tanner: I would love to hear your fondest memory of Karl Barth.

Robert Jenson: Many people knew Barth much better than I ever did, but when I was in Basel for a short time, he was at the height of his fame. People traveled to Europe, eminent theologians and statesmen, and begged a short interview with the great theologian. I showed up one day as a student and said I was working on a dissertation about him and asked would he help me with it. He said yes. He was the most open, approachable person you can imagine to students. Unless you challenged him. Then he would switch gears and treat you as if you were Rudolph Bultmann incarnate or something, a debate in which all holds go. Both ways of acting showed his enormous respect for people. I guess my fondest memory of Barth is when Blanche and I were leaving Europe with the doctoral work behind us, and we traveled one more time down to Basel to say goodbye. It happened that it was the English Language Societate that was meeting, so the discussion was in English. The people there were mostly Reformed, and they tended to listen to Barth and say, “Ja, Herr Meister (Yes, Great Master),” and write it down. Blanche and I were sitting in the back, because we were just there to say goodbye. Finally, in frustration, Barth said something offensively not-Lutheran, and insisted, “Herr Jenson, What do you think about that?” And I was back into conversation again. That’s the last thing I like to remember. I snuck into the hospital room to say goodbye when he was obviously in his last illness. Marcus Barth tried to stop me but I managed to get in. He was unresponsive, so that’s not much of a memory.

Kenneth Tanner: That shows a great affection. And as Jesus said, when you visit the sick you visit me. I’m glad you made the effort. People know you as a theologian, but they can forget that you’re a pastor too.

Robert Jenson: Well, if that’s true, and I hesitate to say that it is, it’s a great honor that people think it. Thank you.

Kenneth Tanner: I certainly do. You’re a pastor to me. I wonder, what does Jonathan Edwards have to say to contemporary American Christians? You’ve said he’s “America’s theologian.” What do we need to hear from him right now?

Robert Jenson: That is a hard question. The book was written on the supposition that America was the nation founded by the Enlightenment and that Edwards was the one theologian who found ways to affirm the Enlightenment in a thoroughly Christian, Trinitarian fashion. The question is, Does the Enlightenment still mean anything to Americans? Or is that whole scenario that I painted overboard? The fact that many people, including Blanche and me, have not been able to vote for president because one party is committed to abortion on demand and the other party is committed to everything for the rich shows that we have arrived at some sort of a stalemate. Whether what we can get from Jonathan Edwards, or any other of those who have been idols in my theological life, will amount to something public, is a hard question. People refer to the Benedictine option in which the church commits itself to communities of its own that are dedicated to prayer and labor in hopes that simply the view of such a community can transform the rest of society. I don’t know. Maybe that’s it. You will understand that at this point in my theological life, I perhaps have more questions than answers, which may not be a bad thing.

Chris Green: What are some of those questions? What are the questions that you’re living with right now?

Robert Jenson: How to pray. All prayer is selfish. There’s no breaking that. And yet we are commanded to pray. So, I pipe up: Dear Lord, here’s what I think you should do. That’s an audacity past dreaming up.

Chris Green: Let me ask you about another great American theologian and what he has to say to us today. How should people be reading you right now?

Robert Jenson: For whatever they can get out of it. I’m not going to prescribe that. It never occurred to me when writing my systematics that people would find them passable. But you say you do. I’m delighted. Run with that. If they clear up intellectual questions, fine. If one essay of mine is bread cast on the water for anybody to pick up and be blessed by it, that justifies my whole effort. So I don’t have an answer to that question either.

Kenneth Tanner: The center of your systematics, of course, is Jesus. You say he is how we know God, period. Perhaps the most creative responder in America to your work is David Bentley Hart. I think it’s not too much to say that he reveres you, yet at the same time he finds some things challenging, particularly how you have approached the changelessness of God and the reality of Jesus. What would you say about the conversation that you’ve had with Dr. Hart?

Robert Jenson: Well, you know, in the book that made him famous, and in essays shortly thereafter, David praised me as some kind of marvel but insisted that at the key moment I had it exactly wrong. The villain of the history of Western theology, according to David, is Hegel. And he found my treating of the futurity of God to be too Hegelian. I’ve always protested that identification. There’s a way in which one can ask flippantly, Post Hegel, can anybody in Western theology be running with anything but some fragment of Hegel? And the answer to that is, No, probably. Am I Hegelian? Yeah, but so what? I don’t think that David finally comes out much different than Karl Barth. He would be the last person on Earth to agree with that, but I’m willing to venture it.

Chris Green: A lot of people, including Hart, accuse you of making God dependent upon history. You have insisted that that’s not true. Could you say again why it is not true that God is dependent on history?

Robert Jenson: It depends on what you mean by dependence. Would God be the God that he is if he had not ordained the history that he has? No, he would not. There’s the question, If God were not incarnate as Jesus, what would he be like? And I have, through most of my career, answered that he would obviously still be triune, but we can’t say anything about how. Lately, I have concluded that also the question is empty. It doesn’t mean a thing. Not only do I propose that there’s no answer to the question, What would God be like if there were not the history that he has ordained, I don’t think one can even ask that question. Not meaningfully. Does God suffer? Same question, finally. And the answer is, the Son of God suffers, but he does not suffer the fact that he suffers. His suffering is his own triumph.

Chris Green: Is that a difference between you and Motlmann?

Robert Jenson: I’m not sure. I have to say I’m not an expert on Moltmann.

Kenneth Tanner: The suffering that takes place is, in your theology, more about who is suffering than how (given the communication of idioms), no?

Robert Jenson: The second person of the Trinity is suffering. That’s dogma. Unus ex Trinitate mortuus est pro nobis. The qualifier, traditionally, is insofar as he is human he suffers. I prefer to say there is no way in which the Son is not human. So, the Son—as Son—suffers, but he does not suffer the fact that he suffers.

Kenneth Tanner: You and I were together with Wolfhart Pannenberg at a conference in Minneapolis in 1999, when he read a famous essay on the resurrection. Tell us about that relationship. How was Pannenberg meaningful for you?

Robert Jenson: When I got to Heidelberg as a naive graduate student, an American, I knew there were things I was going to have to know that I didn’t know. Being so naive, I thought I could just march up to a professor and ask if I could be a student. You weren’t supposed to do that. You were supposed to sit around in seminars until some professor noticed you. But I didn’t know that—so I got an appointment with Peter Brunner. The University of Heidelberg at that time didn’t print a catalog. Professors just tacked up on the bulletin board what they were going to do this particular semester. I knew the one thing I needed to know that I knew practically nothing about was 19th-century German theology. And here was a man named Pannenberg who was lecturing on Protestant theology in the 19th century. I went to Peter Brunner and asked if it would be a good idea for me to take that course. He answered, Well, Pannenberg is a very clever person. Perhaps a trifle too clever. I signed up for the course, and we never got past Schleiermacher. What I got from Pannenberg was the foundation of my knowledge of 19th century Protestant theology. So, I learned friendship, because we did become friends—and got one course, and one book: History as Revelation.

Kenneth Tanner: There are a lot of young pastors and young theologians who are reading you. I wonder if you have a word of encouragement for them in this particular moment, the young men and women who have dedicated themselves to the ministry of the church?

Robert Jenson: Thank you. Make of me what you will. If I inspire you, in any way, don’t thank me. Thank the Holy Spirit, and thank him on my behalf. That’s what I would say.

Kenneth Tanner: Would you pray for us?

Robert Jenson: The Lord be with you.

Kenneth Tanner: And with your spirit.

Robert Jenson: Lift up your hearts unto the Lord. Heavenly Father, be with us in the coming days of trial. We thank you for whatever you have contributed to those days, to the work of Robert Jenson. He does not deserve the credit; you do. But we wish to thank you for it all the same. Amen.

Share this post